The Masked Teacher: “You Must Really Like Teaching French at the U!”

What does the act of walking and the act of speaking have in common? During the ongoing pandemic, these have been the two activities that take up most of my time. They are especially related because, during my walks, various neighbors and friends ask me how my teaching is going. The latest conversations go something like this, “Okay, you made it through teaching French on Zoom. Now you’re teaching French in a mask?! You must really like teaching French at the U!” This is often followed by everyone practicing their high school or college French on me, to emphasize that they could not possibly do this while wearing a mask.

This article marks the end of my trilogy on teaching French during unusual times. The tone here is definitely one of “What’s next?,” tempered by “If you can do this, you can do anything.” It would be easy to simply offer helpful hints on how to teach in a mask, and this article will contain those. These hints will focus on the well-being of the students and communities of learners, as did my first two articles on remote learning. But it also makes sense to explore more here the role of the teacher in a masked classroom because, as is common knowledge, if you are on a flight and the oxygen masks drop down during an emergency, you are supposed to adjust your own mask before attempting to assist others with their masks.

The first day, or the elephant in the room

The first day of teaching my three classes in a mask was similar to my first day of teaching three classes via Zoom. Back in March of 2020, it was all about Zoom, and not about French at all: was I up to embracing all the new technology needed to succeed in remote learning? In September of 2021, it was all about the mask, and again less about French.

The first activity we did in class that day was fill out a Google doc in French about strategies to learn a foreign language while wearing a mask. These were students in advanced French classes, so their vocabulary was extensive. We came up with a set of class rules that included being able to lower your mask to access your water bottle, to avoid dehydration: “Tout le monde doit boire beaucoup d’eau. Il faut être bien hydraté!” We discussed being able to step outside for a mask break, without having to ask permission to do so. In fact, we contemplated holding class outside, sans mask, or as one student enthusiastically suggested, “Avoir la classe dehors!!!!” This would indeed occur later on in the semester. The Google document on the first day was also meant to elicit lots of input from freshmen who may have already attended their classes in masks while in high school. It was an unusual twist for freshmen to feel superior to upperclassmen, all because of their mask-wearing experience.

At the top of my own list on the Google doc was the following: “La prof parle moins pour ne pas avoir trop chaud quand elle porte un masque!” As with courses held via Zoom, this was definitely going to be another semester of a completely student-centered classroom. We confirmed that Google docs would continue to be our best friends, so that group work done outside of class could be shared aloud in class on the big screen, in case students had trouble hearing answers through masks. We figured out how to say social distancing in French (l’éloignement social), so that we’d know if everyone was comfortable with the seating arrangement. Students did not in fact want to be seated too far away from one another because this would lead to difficulty understanding French through a mask. Beginning on day one, I made a point to circulate among the students during group work, which is the cornerstone of engaging students during a language course. I noted on the hints for masked learning a tone of “we’re all in this together” among the students, for example, the use of the pronoun “nous” to describe how speaking a foreign language more slowly may help with listening comprehension: “Nous pouvons parler lentement avec les masques.” This is such practical advice, much like that of another student who wrote that even if we had to have class inside, “Nous pouvons ouvrir la fenêtre.” On that first day when students signed up for group work they also became acquainted with the gender-inclusive pronoun “iel” in French. Using the correct pronouns allowed everyone to celebrate their individual identities, despite having to wear a mask.

My favorite rule, which I posted before class, concerned our inside speaking voices which had to turn into outside voices: “Tout le monde doit parler très fort non seulement à cause des masques mais aussi à cause de la machine qui nous fournit de l’air purifié (le système HVAC).” The HVAC machines made as much noise as the window air-conditioners that used to be installed in Folwell Hall many years ago before the building was given a make-over. Back then, a teacher had to pick between being overheated and being heard. Luckily, the HVAC machines were removed from my classrooms at some point. After my first day of masked teaching, I chatted outside with a lecturer of German. Rather than discussing the curriculum for our language courses, we ended up discussing the volume we needed to maintain in class so that the students could hear us through our masks. We had fun comparing the French command “Parlez plus fort!” with the German command “Sprechen Sie lauter!”

During Welcome Week in August, I had attended several meetings with colleagues in my department concerning masked teaching. I had asked a fellow French lecturer if he thought it might be a good idea for me to get a microphone for class. His response was that I was a loud person and that no microphone would be necessary. This bit of humor made the bleak prospect of teaching in a mask quite funny and reminded me of comments I’d read about myself on the ubiquitous website “Rate My Professors.” Back in 2010, a student pegged me as “your stereotypical French teacher” because I was “loud and obnoxious.” On this same site in 2007, the same adjectives were applied to my teaching style: “She may come across as loud and obnoxious, but come on, those are the best kind of French teachers.” Being loud and obnoxious in a mask might not be such a bad thing! At the very least it was funny, like a good Saturday Night Live sketch.

As with Zoom teaching, humor became key for me in creating thriving communities of learning. The Google doc with hints in French for learning in a mask contained a New Yorker cartoon from September 6, 2021, with younger students wearing masks, while their masked teacher urged them to “Please go inside the box,” which consisted of individualized desks surrounded by plexiglass. This is obviously a take on the expression “to think outside of the box.” We had fun describing in French why this cartoon was at once incredibly funny and truly educational now that we were back on campus during the pandemic. We confirmed the importance of group work when learning a foreign language. This made me think of the best action item during my Welcome Week meetings, which had been written on the whiteboard

Merrily we mask along…

Another favorite cartoon of mine from last fall was from the comic strip “Zits,” published on September 19th, 2021, in my local paper, The Star Tribune, and reposted on Twitter. The cartoon amused me because of its wishful thinking, the idea that the “new normal” was that students had returned to school after Zoom learning as if nothing had ever interrupted their previous learning. In other words, the high-school students in this classroom are not wearing masks as they sit at their individual desks with their books and papers, ready to learn! Their teacher is also maskless. However, one student, named Pierce, sits apart, comfortably ensconced in a Lazy Boy recliner, barefoot and in his pjs, laptop, and snacks at the ready. Pierce calmly declares, “Some of us came to like distance learning.” This definitely sums up the sentiment of many college students upon their return to campus. Some of them miss the convenience of Zoom learning.

I think after seeing this cartoon in the newspaper it would have been easy for me to predict the response to one of my mid-semester survey questions during the fall of 2021: Do you feel like you are now working hard in this course because you got into working hard in an independent way during Zoom teaching, or do you feel like it has taken you a long time to readjust to live classes due to having learned remotely for 2 and a half semesters? There were two responses possible to this question: 38% of students in my two sections of French 3015 (Advanced French Grammar & Communication) indicated that I am having trouble readjusting to live classes because I got so used to remote learning; 52% indicated that I am working hard in this course because I got used to working hard in an independent way during Zoom learning. For my section of French 3016 (Advanced French Composition and Communication), the second course in the language sequence, the statistics were, interestingly enough, reversed with 64% indicating they were having trouble readjusting and only 36% feeling adjusted. These advanced classes of French were small classes, but I think the number of students having trouble readjusting is significant. In reading the Iowa State Daily, I was amused to discover humor columnist Omar Waheed’s take on students who missed Zoom learning at the close of fall semester, 2021: “Good luck on your finals. You’re going to need it since you can’t cheat on them from the sanctity of your home anymore now that we’re doing tests in person again.”

After a few weeks of fully indoor classes and repeated explanations about how I felt face shields were only safe for professors lecturing in an amphitheater, we finally ventured outside. Though I was not at all sure if this was allowed, I was inspired to go outside by witnessing an Italian lecturer having lots of fun outdoors with her students at the start of the semester. The first day we went outside for the last five minutes of class just so we could see the full faces. A female student exclaimed to her male classmate: “Je ne savais pas tu avais une barbe!” I then interjected “Quelle surprise!” which caused lots of laughter. Another student was bold enough to ask a classmate about the origins of his unusual first name, since being maskless created a friendlier atmosphere. Here were some student takes on outdoor learning from my mid-semester survey: “I think going outside for class on warmer days has helped a lot with my understanding of the class”; “I really do like going outside when possible and having more of a connection with people seeing faces.” Students in French 3015 seemed a little panicked when I told them that I would be happy to go outside in snow boots second semester for French 3016. They are currently waiting to see if this will really occur.

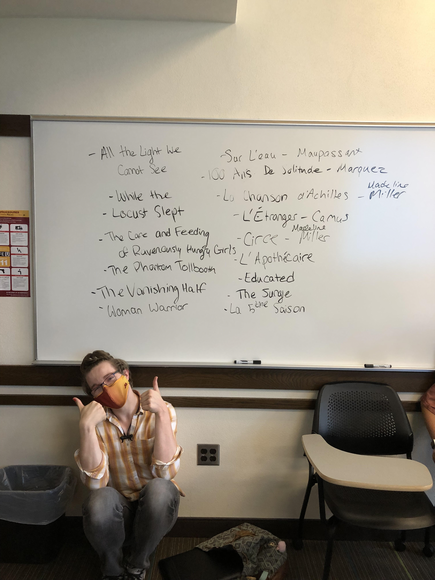

We came up with a routine for the remainder of the fall semester during which we’d use the overhead projector for half of the class inside, to check grammar exercises in the workbook or share answers from a Google doc. Sometimes, we would share ideas on the whiteboard, for example, in this photo, a student jotted down titles of books that had never been turned into films, inspired by our reading of an article entitled “Les livres cultes qui résistent au cinéma."

Then we’d have the second half of the class outside for a more open discussion on readings and films during which students could get away with just consulting paper copies of materials, such as the coursepack. Perched on the retaining wall outside of Folwell Hall, with just enough distance from one another, students were also easily able to use their laptops, though I never quite figured out how to get rid of the glare from the sun on my own screen. Students were eager to be the center of attention while having class outside and would even agree to take my professor spot in front of the whole class when sharing their opinions. Even outdoors, I was still able to get students to call on their classmates when going over various homework assignments. For the remainder of the semester, colleagues would enthusiastically greet me by saying, “I saw you having class outside!”

Setting up opportunities to speak French without a mask was key during the fall of 2021. So, just as I had during remote learning, I continued creating short videos in which I explained grammar points. These videos were formal in that I spoke with slides containing the grammar points, but they also had a fun side to them in that the virtual background every week would match the reading or film we were watching. My favorites were the coffee shop, Central Perk, from the series Friends, to match the theme of “l’amitié” in French 3015 and la rue Didouche Mourad in Algiers, when we were watching the Algerian film En attendant les hirondelles (French 3016) or reading the novella L’hôte by Albert Camus (French 3015). To celebrate Québécois cinema (the film Monsieur Lazhar in French 3016), I placed myself in front of the Château Frontenac in Québec City. These videos were a hold-over from Zoom teaching when students had expressed to me how they often watched the grammar videos several times, especially right before the exams. Here is a typical reaction to the weekly videos from the mid-semester survey: “I find it helpful that the grammar videos are online and I can watch them at my own pace to make sure I understand them.” During “live” class we would be focused on precise questions students had either about what I’d said in the video or what they’d read in the textbook, or as a student explained in the mid-semester survey, “bringing questions to class, which freed up some time to focus on what needed attention.” We definitely had more time to analyze challenging exercises in the workbook. This method redefined for me the notion of the flipped classroom because students were never alone when they first had to face sophisticated grammar topics. I was there virtually guiding them through explanations in the textbook, as well as exercises in the workbook and in the PowerPoint.

The second maskless highlight of last fall was cultural exchanges with students at l’Université Paul Valéry in Montpellier through the TandemPlus Program at the Language Center. Students were given four topics related to the curriculum and had to set up virtual meeting times to chat with their new French friends. Here are some typical, enthusiastic descriptions of this French-speaking activity from my mid-semester survey: “I think the échanges culturels have been my favorite part of this class. My partner in Montpellier is very friendly and easy to get in touch with, which I appreciate. Our meetings give me the chance to learn more about France, what real French people are like, and about French culture”; “I really love the échanges culturels because I am lucky to have a very understanding partenaire: she is a good listener and just a good person.”

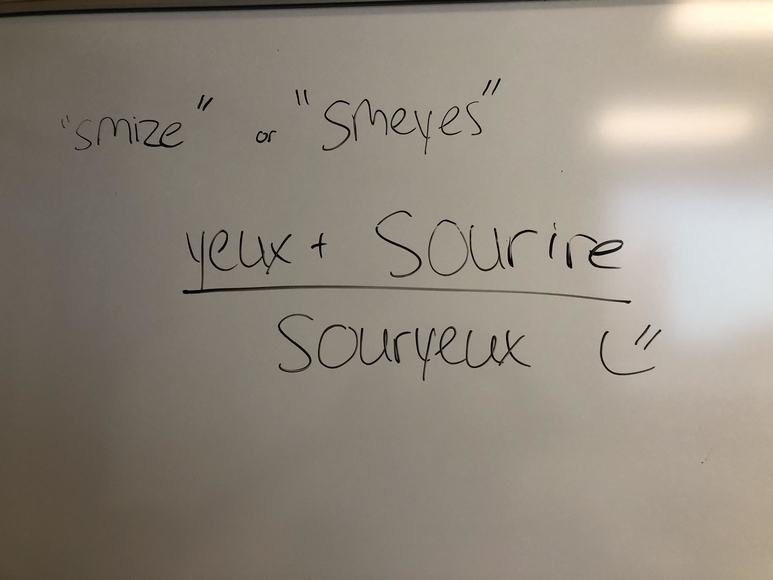

Masks remained a central focus throughout the fall semester. For example, one student complimented another on having found a disposable, surgical mask that was pink. We joked about seeing “la vie en rose” during a pandemic. A student instructed me on the art of wearing dangly earrings (des boucles d’oreilles pendantes) while sporting a mask, as I had given up on this art when my earrings got tangled in the mask, and so had switched to stud earrings. But, the very best day regarding our constant discussions of masks was when we came up with the French equivalent of the newly coined term “smize.” This is when you smile with your eyes, which is so important in a mask. We came up with the French equivalent of “souryeux” and a student wrote our new word on the whiteboard. And, of course, I could not help myself and sang “You’re Never Fully Dressed Without a Smile” from the musical Annie.

Les feedbacks:

I have French friends who have lived stateside for many years, and I always marvel at how they have incorporated so many English words into the French they now speak as American citizens. My favorite used to be “J’ai un meeting,” but now I have a new favorite during these pandemic times: les feedbacks. A French grad student with whom I was friends before the pandemic, told me how astonished she was at the amount of feedback that American professors gave to students, as compared to their French counterparts. As with Zoom teaching, I have tended to go overboard with feedback to students during masked teaching. I want my students to continue to feel valued and successful with their language learning during these pandemic times. It was therefore incredibly meaningful to me when students indicated how important my feedback was to them in their mid-semester surveys:

--“I personally love the little messages on the assignments—it helps me know that you are truly reading them and not just skimming over them for grading (I do think other profs do this sometimes).”

--“I think the feedback on the work turned in so far has been helpful. I appreciate corrections and praise for using certain grammar conventions or vocab. I am able to tell when I am heading in the right direction and which things I need to fix.”

--"The detailed feedback really helps, especially the encouraging comments like bien décrit. These may seem like small things, but they really make a difference.”

I would say that my tolerance for franglais from students really increased during masked teaching. It would be impossible for me to make up these funny, franglais sentences from the mid-semester survey:

--"Now I would add that people should speak up and try to enunciate their words more since it’s hard to hear in the mask. Talking slower may be a bit tedious, alors je pense making sure everyone is heard c'est plus important.”

--"I'd say that wearing a mask is a bit frustrating (and it feels terribly hot when you speak while wearing a mask), but je me débrouille.”

--"So far, the bavard-ing before and after class in a mix of French and English has been helpful and fun.”

The verb “bavarder” had in fact been a favorite one for us to conjugate all semester long, despite our masks. A cartoon we had discovered online became part of the mid-semester survey simply because it suggested that chatting could still take place in a classroom with masked students. One student in the cartoon declares, “C’est pratique de porter un masque en classe, on peut discuter avec son voisin…,” to which a classmate replies, “La prof ne voit pas nos lèvres bouger, elle ne sait pas qu’on bavarde!”

Of course, I am also grateful for the oral feedback students give to me during masked teaching, not just thanking me at the end of the class hour, as they did during synchronous sessions on Zoom, but also encouraging me throughout the semester. The funniest example was when we all looked together at the mid-semester survey results for the question, Now that you've been taking this French class for about half of the semester, how would you describe the current vibe in class with everyone wearing masks? The results were as follows:

- upbeat = 27%, workable = 73% (French 3016)

- upbeat = 14%, workable = 71%, frustrating = 14% (2 sections of French 3015)

Not a single student picked the fourth choice, the adjective “depressing,” and yet I lamented that not everyone had picked the adjective “upbeat,” but the students assured me that I should be happy with the 70% results for “workable.” After all, we were here to work! In any case, I think this remark from the mid-semester survey is definitely upbeat and demonstrates the resiliency of college students during the ongoing pandemic: “Despite the impediment of the masks, I still feel as though I was able to learn. While they have slightly dampened our abilities to practice speaking out loud, I do not feel that it has been so bad that we haven't been able to make significant strides in our skills. It helps that we have a small, closely-knit class.”

A highlight of students supporting students in French 3015 was the peer-editing that took place for the writing assignment of a récit, or first-person narrative. Students evaluated the content and style of their partner’s work, in addition to commenting on grammar and syntax. But what stood out the most for me during this peer-editing activity was how carefully the students had read each other’s work, and how they wanted to encourage one another in their French writing, as much as I encouraged them. In encouraging their peers to improve their writing, they were also encouraging themselves. This has got to be one of my favorite remarks of all time written by a student struggling to learn a foreign language, again at the mid-semester point: “I have felt encouraged, I think it is more a matter of me trying to encourage myself.”

“Groundhog Day,” or “Un jour sans fin”:

I have always liked the French translation of the American movie Groundhog Day, and as I returned to campus in January of 2022, I would say that Un jour sans fin really expressed how I felt about a second semester of teaching in a mask. A student had warned me during one of my last Zoom office hours in the fall that both students and teachers should now always be ready for new ways of learning, or as she so well stated in English: “This is not the last time something big happens and we have to move online.” But she also expressed great optimism and underscored to me that, “I learn so much better going to physical classes.” Students once again had to post introductory videos on the course websites for the spring semester of 2022 and, though I told them they could recycle their videos from last semester, most chose to post something new. And yet students were still discussing masks! The new twist was the harsh Minnesota winter: “Les masques sont difficiles à porter à l’école. Mais les masques gardent mon visage du froid. C’est l’hiver maintenant et, à Minneapolis, il fait très froid.” With the students I knew from the fall, we reminisced on the first day about our fun classes outdoors, and therefore hoped that the groundhog would not see his shadow this year so that we could return to seeing each other’s faces. I explained that Groundhog Day did not exist in France, but that the French were still fascinated by this American tradition concerning la marmotte. However, the best “live” mask discussion was with a student who had spent the previous semester studying abroad in Montpellier at the Université Paul Valéry. She shared with us the strict rules for masks and vaccination passports both on- and off-campus during her extended stay in France.

I still found myself saying to students “Répétez, s’il vous plaît,” “Parlez plus fort,” or “Excusez-moi?” Students would also use these cues from across the room to alert their classmates of trouble hearing through a mask. As with Zoom class, the level of politeness with each other remained extremely high. We again found ourselves returning to the Google doc with the hints for learning a foreign language through a mask from the fall. We again identified words that were particularly hard to pronounce in a mask, such as “probablement” or “linguistique” or “architecture.” The difficulty of pronouncing French words in a mask brought me full circle to the first article in my trilogy in which I described reading La peste by Albert Camus with students during Zoom classes held in the summer of 2020. Back then, we could only imagine French class in masks, while reading this description from the digital version of the novel: “Chaque fois que l’un d’eux parlait, le masque de gaze se gonflait et s’humidifiait à l’endroit de la bouche. Cela faisait une conversation un peu irréelle, comme un dialogue de statues” (page 190). Even before I started teaching in a mask, I could not escape thinking about them, as in the summer of 2021 I reviewed a novel entitled Hôtel Beauregard (2021) by Thomas Clavel, which featured this same quote by Camus as the epigraph for the first chapter. This dystopian novel was all about the controversy surrounding mask-wearing during a global pandemic.

What I have noticed most of all at the start of 2022 is that students are still so concerned about each other’s well-being. When classmates were already ill the first week of classes, their friends promised to help with catch-up activities. This made me think of students from the fall of 2021 who had set up review sessions before each exam in “The Toaster,” a study room in Walter Library on campus. I was part of these sessions via Zoom during daytime hours, but I also found out that such sessions took place late at night.

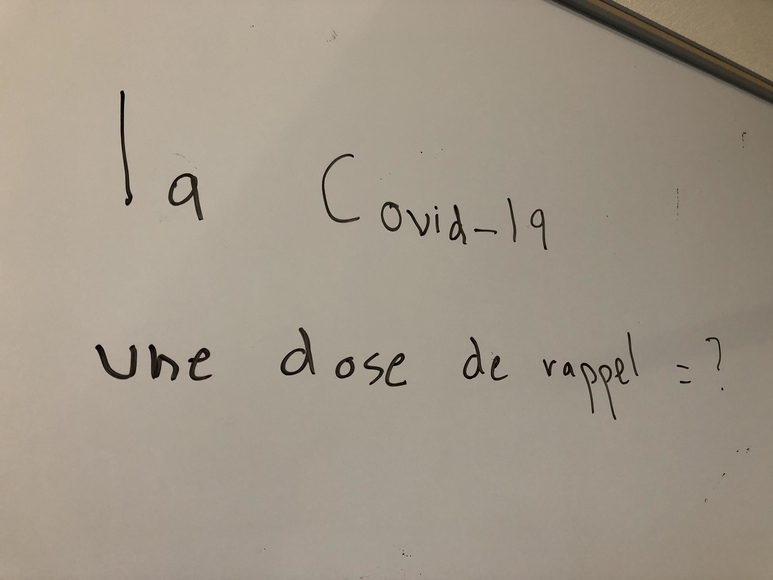

The level of kindness among these students was off the charts, as one sincerely asked me if she could “donate” one of her next exam points for a correct answer to a student who was having more trouble with the grammar sections on the exams than she was! I said, “Ce n’est pas possible,” but acknowledged such a generous act of friendship. I also recall the last day of classes in the fall when a non-traditional student, a retiree, thanked his partner for the group work throughout the semester and the class in general for letting him participate in class as an auditeur libre. This student was in fact a doctor, so he wrote on the whiteboard that same day the vocabulary for “booster shot” (une dose de rappel).

A student had written an email to me in December that contained a wonderful franglais version of this vocabulary: 'boosterée' (je viens de créer un mot je crois). Thus, it came as no surprise that in one section of advanced French during the first week of classes in 2022, we were still focused on translating words that could help us better cope with a pandemic, in this case, a large sticker on a student’s laptop: “Choose kindness.” We decided that “Partagez la gentillesse” sounded better than “Choisissez la gentillesse.” We found this article in French about sharing kindness during a global pandemic.

I had described in my second article a Thank a Teacher award from the spring of 2021 during remote learning. I actually also received such an award for my masked teaching in the fall of 2021. I could not believe that this student from French 3015 was so enthusiastic to keep learning French while wearing a mask: “Very lucky to have had her as a teacher and can’t wait to take her next class in the spring, French 3016!” I admire this type of resiliency in a student, and even more, I admire how much French means to her: “She has made me advance in my French skills and reminded me why I chose to take French because of how much I love the language.” This resiliency is also evident in the following words from the mid-semester evaluations during the fall of 2021, which continue to inspire me through another semester of masked teaching: “Masks obviously aren't the best when speaking/understanding as it messes with clarity sometimes, and in a different language it makes it harder. But I don't think it has negatively impacted any of my learning—it’s just something that needed to be adapted.” Adapting is quite obviously an accurate description of what I have been describing throughout my trilogy. Adapting through creating communities of learners brings the trilogy together and so I would like to end here with how language learning only exists when a strong community is created or as a student wrote so eloquently on the end-of-semester evaluations: “She was able to create a community of students who are all okay with talking, studying and interacting with each other both in and out of the classroom.”

Groundhog Day for sure, so here I am wearing my Eiffel Tower mask on the first day of class in January of 2022 (picture on the right), just as I had on the first day of class in September of 2021, smizing or souryeuxing my way through another challenging semester with engaged students who are always willing to try and to support one another in their love of the French language. Yes, this consists of le selfie, and, yes, I have a similar picture from the fall, but I am not smiling in that picture because of fear of the unknown (picture on the left). The compliment from students of “J’aime votre masque!” on day one has become a comforting and smile-inducing refrain as I realize that I do indeed really like teaching French at the U!

All of the photos in the body of this article were taken by the author. Permission required to reproduce them.