Time & History: The Story of Mendieta at Minnesota

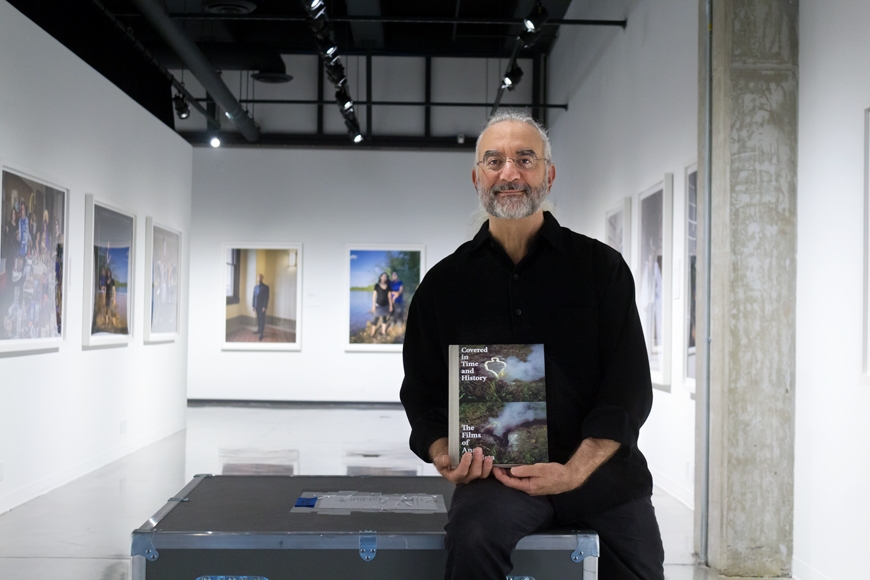

Howard Oransky, director of the Katherine E. Nash Gallery at the University of Minnesota

The year is 1978. Howard Oransky is 23 years old, waiting for his girlfriend, Anna R. Igra, the editor of UCLA’s feminist newspaper, to meet him in the newspaper’s office. He spots, in a stray magazine titled Heresies, the image of a woman’s silhouette made of animal blood, created at an archaeological site in Mexico. Oransky was “amazed at the way the artist was engaging with these different aspects of human experience in terms of her own personal history and collective history, merging the present with the past and locating herself in a particular geographical, cultural, and archaeological setting, and bringing all that to the fore with very simple materials.”

Howard Oransky had seen his first glimpse of Ana Mendieta’s art, an experience that would stay with him for the next forty years of his life, culminating in an international exhibition, a catalog published in English and in French, and a bittersweet trip to Paris.

A Fascination With Film

By the late 1970s, a movement called “land art” was in full swing. Oransky had seen the work of male artists who had dug trenches and moved earth for miles to speak of volume and absence in what he describes as a “formalist” and “interventionist” way. Mendieta’s work, he recalls, “was totally the opposite. Instead of it being this dramatic alteration, it was very ephemeral... She was collaborating with the earth as an equal partner.”

In 1984, six years after his first encounter with Mendieta in a university lobby, Oransky had completed his graduate work at CalArts and moved to New York City with the UCLA girlfriend he had since married. A year later, Mendieta died in the same city, and when the first career survey of her work was presented at the New Museum two years after that in 1987, Oransky and his wife Annette went to see the exhibition, where he had another eye-opening experience at the hands of Ana Mendieta’s short films. His fascination with her film Anima, Silueta de Cohetes (Firework Piece), which portrays the silhouette of the artist through fireworks, fueled an interest in her filmic work that persisted during his years in New York and subsequent employment at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. In 2005 Howard and Annette drove to the Des Moines Art Center to see the Ana Mendieta exhibition organized by Olga Viso, and two years later Oransky met Viso when she became director of the Walker Art Center. It was then in 2007, with Viso’s encouragement, that Oransky began thinking about a films exhibition. In 2011 he was hired as the director of the Katherine E. Nash Gallery at the University of Minnesota. When art department professor and soon-to-be chair Lynn Lukkas asked what project Oransky wanted to lead at the Nash Gallery, he didn’t hesitate to respond with “the first exhibition devoted to the films of Ana Mendieta” and he invited her to join as co-curator. “I have been a lucky man,” Oransky noted. “On more than one occasion I have been in the right place at the right time. It was thanks to Anna that I learned about Ana, and from there one thing led to the next.”

Locating the Lens

As an artist, Ana Mendieta was prolific, producing gorgeous work from 1971 to 1985 that included drawings, photographs, sculptures, performances, and installations. Amid all of her different media, Oransky stresses that “this is a lot for somebody at a young age who is also traveling widely, working in the US, working in Mexico, making all this work, and making all those films.” And like her other works, her films are “just so rich and layered and textured and surprising,” Oransky explains. “There's so much to be gained from looking at these films; she takes on so many big, philosophical questions of history and culture and identity.”

Historically, Mendieta was leading a charge as well. The 1960s and ’70s were a time of radical change in the visual art world. As Oransky explains, “if you come here [to the University of Minnesota art department] in the spring and look at our MFA show, you’ll see everything. Somebody will be making sculpture, film, drawings, performance. All of that now seems perfectly legitimate and normal, but back in the 1970s, that was radical.” Mendieta, Oransky notes, “was actually at the center of this multidisciplinary activity. She was making a lot of films and a lot more than anyone really understood before.”

Working With Time and History

Oransky devoted the next four years of his life to Mendieta’s films, jetting back and forth between the University of Minnesota and New York to work with the Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection and the New York branch of Galerie Lelong & Co. in reviewing tapes and cassettes of the original films. Then, in a meeting, Oransky “heard somebody say ‘we’re going to research and publish the first complete filmography of all of Mendieta’s films and include it in the exhibition catalog.’” When he realized that person had been him, he understood that he had just “vastly increased the scope of work that we [the Art Department and the University] were embarking on.”

Jane Blocker, professor of art history at the University of Minnesota and author of the book Where is Ana Mendieta? wrote a successful Grant-in-Aid of Research, Artistry and Scholarship that provided the seed money to hire a graduate student to work on the exhibition catalog: Laura Wertheim Joseph, who ultimately wrote the filmography that Oransky had announced that day, as well as another essay that traced the history of the conservation of Mendieta’s films. The catalog was rounded out with writings by Oransky and Lukkas, as well as Raquel Cecilia Mendieta, John Perreault, Michael Rush, and Rachel Weiss. Critical financial support from John Coleman, the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Harlan Boss Foundation for the Arts, and numerous other sources enabled the project to move forward toward completion. In the end, the curation was comprised of 21 films, 27 related photographs, and a short documentary film by Raquel Cecilia Mendieta, the artist’s niece and film archivist of the Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection. It is the largest gathering of Mendieta’s films ever presented as a full-scale gallery exhibition. The catalog was co-published by the Katherine E. Nash Gallery and the University of California Press and was awarded Best Art Museum Exhibition Catalogue Design by the American Alliance of Museums.

The exhibition, Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta, premiered at the Katherine E. Nash Gallery on September 15, 2015, before closing up on December 12 to begin its international tour. The exhibition traveled to the NSU Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale, the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, the Bildmuseet at Umeå University in Sweden, the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, and finally to the Jeu de Paume, the national museum for media arts in Paris, where it is on view until January 27, 2019.

A Mendieta Festival

An Art Lover’s Paris, a trip organized to view Covered in Time and History at the Jeu de Paume, originated with Karen Desnick, owner of Metropolitan Picture Framing in Minneapolis, and Karen Kaler, wife of UMN president Eric Kaler, who were both early supporters of the Mendieta exhibition and had assisted the project with fundraising. They approached the University’s Alumni Association with the idea of an exhibition-related event in Paris that would allow them to invite more people who were affiliated with the University. Oransky liked that the trip allowed the travelers “to see the exhibition in the context of the contemporary art world in Paris.”

During the five-night stay in Paris from October 12 through 18, travelers interacted with Oransky and Lukkas. Before attending the opening reception at the Jeu de Paume, the travelers converged at another, companion Mendieta exhibition hosted by the Paris branch of Galerie Lelong & Co. The group spent their remaining days touring and experiencing other museums and artists’ studios in Paris, as well as the FIAC International Contemporary Art Fair, where Mendieta’s work was also represented by Galerie Lelong & Co. At the same time that her work was on show in these three different Parisian venues, the French translation of the exhibition catalog was co-published by the Jeu de Paume. Paris became a veritable “Mendieta festival.” Within the first few weeks of its opening, over 50,000 people came to the Jeu de Paume to see Covered in Time and History, the first one-person museum exhibition of Mendieta’s work ever presented in France. Coverage in the media has been wide, including a 2-page review in Modern Painters magazine.

The Future of Film

The December issue of Artforum magazine includes Covered in Time and History among its list of Best exhibitions for 2018, describing the gallery experience in Berlin as “exquisite.” For Oransky, the January 27 closing of Covered in Time and History in Paris will be the end of an era forty years in the making. The photographs and films will return to Galerie Lelong & Co. in New York, and the media equipment will be absorbed into the art department for future use. In four-to-five years, Oransky and Nash Gallery assistant curator Teréz Iacovino plan to stage a feminist film exhibition with it. Until then, Oransky hopes that other curators and students will be motivated to do more research into Mendieta’s films. “We are only showing twenty-one films, but she made 104,” he explains. “So there are another eighty films there to be seen and studied. And of course, the writing we’ve done on those twenty-one films are just our perspectives, and there are many other perspectives. So I hope there will be future research and scholarship and articles and books that will be written about her films.”

As far as Oransky knows, before this catalog was published, there had only been one substantial article written about Mendieta’s films, for Olga Viso’s exhibition catalog in 2004. He finds that troublesome and explains that he would be interested in seeing in the future an historical timeline of the films that would “go in both directions,” simultaneously locating what was going on in Mendieta’s works as well as relevant developments in the media and visual arts along with the wider political and historical context. “It’s not going to be me,” he laughs, “but somebody could do it... Our catalog provides a foundation for future research -- there’s a whole lot more that needs to be mined and researched and written about.”

This story was written by an undergraduate student in CLA.