On Purpose: Portrait of Communication Studies

All of our major challenges—achieving equity, justice, public health, ethical use of new technologies, and sustainability—hinge on improving our understanding of communication processes.

We began as the Department of Rhetoric and Public Speaking from 1907 to 1920. After a short merger with English, Frank Rarig led the charge for an independent speech department in 1927 with three foci: rhetoric and public address, drama, and speech pathology. As theatre and the speech and hearing sciences became their own departments in the 1960s, the Department of Speech Communication was born. In 2002, we became the Department of Communication Studies. Throughout, we have engaged students in understanding how citizens, leaders, and professionals might more effectively gain and apply communicative knowledge in practice, across a variety of changing contexts and media.

As the discipline that most directly and purposefully studies human communication, our students, faculty, staff, and community partners conduct research that translates into the public good. That is why communication studies was born in Midwestern land-grant institutions like the University of Minnesota, and why it remains an integral and thriving discipline in the College of Liberal Arts. Communication is much more than the simple process of translating information from speaker A to listener B. Communication is a “constitutive process.” Meaning is made, material is moved, and reality itself is created through the communicative act.

Consider World War II. A “fight on the beaches” is artfully evoked, an audience responds, and a war turns. Billions of people vicariously experience those “beaches,” a reality mediated through radio, film, music, and television. Meanwhile, meaning is translated, negotiated, and remade in trillions of interpersonal exchanges, mediated by organizational frameworks and culture. As communication studies researchers, instructors, and students, we study communication at each of these levels.

Knowing how these negotiations work is crucial to modern life. The Huffington Post’s Jason Schmitt, in a piece entitled “Communication Studies Rise to Relevance,” explains why:

“In many ways communication studies is the right offering at the right time. The discipline is extremely well positioned as the digital economy, social networking and the move toward media creation rises to prominence. Concepts that may have been more abstract for students fifteen years ago such as relationship networks, group communication, and media theory are becoming vitally relevant knowledge that a wide ranging student body want to obtain.”

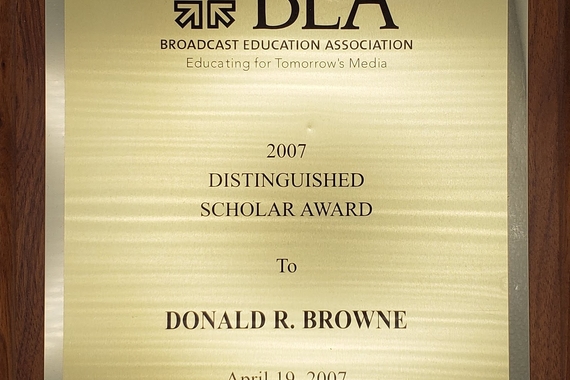

In this photograph we capture and connect our areas of study: rhetoric, speech, media studies, media production, interpersonal communication, and organizational communication. Scholars in each of these fields ask similar questions regarding the nature, meaning, and matter of human communication, differentiated by scale, media, and purpose.