From the Bronx to Cape Town: Making College Possible

After the 1994 South African elections brought Nelson Mandela to the presidency, PhD alum Richard Donovan was contacted by The Ford Foundation; a committee of the new South African government was looking for models on how to build a more equitable education system. Donovan, a leader in the Open Admission push of the 1970s as Assistant Dean of Faculty and Associate Dean for Educational Development at Bronx Community College, CUNY, took on the project, working with South African educators and policy makers for 13 years, “very much as a listener,” he notes, on the phone from his winter home in Miami. “The last thing that the South Africans wanted was know-it-alls from the States. But they did want to bounce ideas off us and learn more about our programs.”

The South African task force that eventually visited New York saw in the US a version of what they were dealing with, says Donovan: a system that had long kept college education out of reach of the majority of underprepared high school students (often poor and people of color). In response to an explosion of such students entering college through the 1960s and ‘70s, US higher education had initiated a range of new programs and collaborations. “The South Africans were curious about the mistakes we had made and the successes we had,” says Donovan. They wanted to know about bridging programs to ease the transition for rural students entering selective urban universities, about writing centers, about improved high school teacher training.

“High school students were being

taught the narrative essay, and

they were coming into the

university system of New York

and being tested on their ability

to write argumentative essays.”

- Dr. Richard Donovan

How did a Shakespeare scholar from the Midwest end up meeting the current South African president, Cyril Ramaphosa, and earning bonus miles flying to Cape Town multiple times a year?

When Richard Donovan left the University with a PhD in English Literature in 1968, he sought the path of most doctoral graduates at that time: “a good position in a college in an interesting part of the country,” as he remembers. The newly minted Dr. Donovan was enticed by a chairmanship at Nazareth College of Rochester, then a Catholic women’s college in upstate New York. However, “I kind of got side-tracked,” he says with a laugh.

After two years, a postdoctoral fellowship in the US Office of Education lured him to Washington DC, amid the foment of early 1970s social unrest. In this “oddly very creative part of the Nixon administration” tasked to explore educational innovation, he found a like-minded cohort of 19 postdoc fellows. "It was impossible back then not to be aware of much of the stuff that was going on," Donovoan says. "Societal change about basic questions, basic assumptions being challenged—about who should be educated or how you educate. Learning as part of my postdoc that there were all of these innovative programs beginning around the country whether it was Texas, Pennsylvania, or New York City, it seemed to me that that was where I wanted to put my energies and my life."

"Open Admissions" and meaningful access

“Most significantly for me,” Donovan recalls, “we went to New York City to oversee the beginnings of the Open Admissions Program, the planning for it.” Beginning in fall 1970 with City University of New York (CUNY), the new policy required only a high school diploma or GED for entrance to CUNY colleges. In a year, system enrollment nearly doubled, with Black and Latinx student enrollment increasing threefold. Donovan wanted to be in New York City, in the middle of the excitement. “I chose Bronx because they made me in effect the head of the Open Admissions Program, as Assistant Dean for Faculty. So I got into it both in the classroom as an English teacher and as an administrator. And that really set my career path.”

For Donovan, the open door policy represented just the beginning of an essential expansion of access. “I was concerned with meaningful access. It wasn’t just students getting in; they were coming with gaps in their backgrounds. With my fellow admissions coordinators, we were looking at the lack of coordination not only between two-year and four-year colleges and universities but between high schools and colleges. It was a lack of interface in terms of curriculum, in terms of advisement, in terms of preparation, especially for disadvantage students, often students of color.

“High school students were being taught the narrative essay, and they were coming into the university system of New York and being tested on their ability to write argumentative essays,” he goes on. “So there’s a disconnect. We had meetings, breakfasts, workshops, where faculty from the colleges and the high schools got together and talked about how we make it a more accessible transition. That conversation between sectors was probably at the heart of what we did.”

As Associate Dean, Donovan also oversaw the college’s grants program. A facility for writing grant proposals led Donovan to found and direct the National Center for Educational Alliances (NCEA) through Bronx, creating national and international programs in school-college collaboration, transfer, and faculty development. “In the late 1980s, I founded a consortium of colleges and universities contending with the issue of expanding access, meaningful access, for underprepared students,” he says. “Eventually my national office coordinated 16 city-wide partnerships, first for the Fund for the Improvement of Post-Secondary Education and then for The Ford Foundation.”

This funding supported Donovan’s ongoing work with six different consortia in South Africa. He secured Ford Foundation funding to create, in the late 1990s, an international conference bringing over 100 representatives from American schools to meet and travel and compare notes with South African educators and administrators, in a traveling “roadshow” across the country. “Out of this came a number of informal exchanges between American schools and South Africans,” says Donovan. Under Donovan’s direction, NCEA was awarded more than $11 million in federal and foundation grants from 1976 to 2007.

Influence of the U

And all along Donovan taught Shakespeare and drama to students at Bronx, and later Florida International University and Miami Dade College. “In the classroom, and I would give a lot of credit to the U for this, I really cared and thought deeply about what I was teaching. I think the authenticity of my love for literature helped. And I got that in part at Minnesota through the passion of people like Samuel Holt Monk, who taught eighteenth century, and Bob Stange, an electrifying teacher of the nineteenth century, and other teachers who were our role models. Jack Levinson. Dennis Hurrell, my dissertation director.”

Mr. Monk, as Donovan still calls him, invited him to come along while the professor was working for two years at the Folger Shakespeare Library in DC, helping Donovan get support, space, and resources to finish his dissertation on Shakespeare's villains. “A wonderful gift he gave me,” he says. “These were good teachers who also kept their eye out for you.”

Donovan retired from his work with South African and US education consortia in 2007. But he’s still teaching at both Bronx and Miami Dade. “I love it,” he says. “I love the intergenerational pop, I love the fact that a lot of my students at any of these colleges are relatively new if not totally new to Shakespeare, and I love the opportunity to share my knowledge and excitement with them. And give it the best shot I have.”

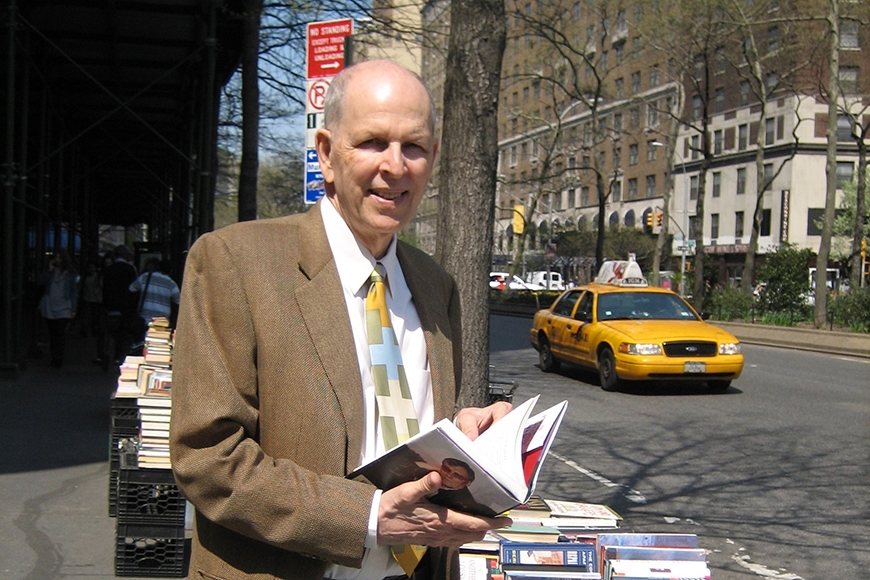

Donovan's recommended reading:

- The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age, by Leo Damrosch. “This eighteenth-century group of masters, Samuel Johnson, Richard Sheridan, and others, formed an informal but really quite dynamic club in London over a period of years. It’s just fascinating to see these people who I haven’t been with in some time come back to life.”