Piecing It Together: Searching for Stories of Icelandic Women

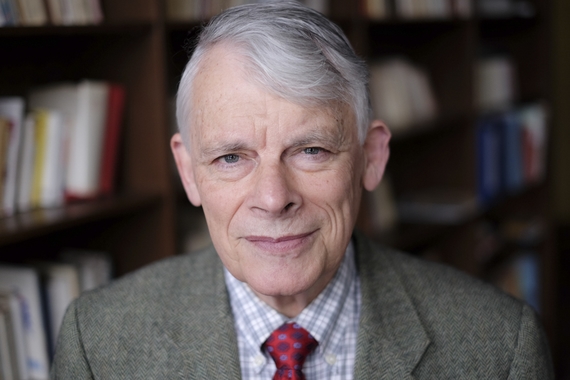

“Being a woman who had to fight for the right to do what I want to do just because I’m a woman—that kind of led me into all this,” says Lena Norrman, a lecturer in the Department of German, Nordic, Slavic & Dutch.

When she’s not in the classroom, Norrman researches women in Scandinavia during the Viking Age and the early Middle Ages. Her most recent studies focus on the stories of women in approximately 1240 CE. “I have always been interested in strong women, women who [were] silenced,” says Norrman, whose own experience with gender discrimination was a motivating factor in her research. “I had the opportunity to speak out.”

A Past of Adversity

Norrman, a native of Stockholm, Sweden, has always had a passion for learning, but after receiving her undergraduate degree from Uppsala University, she faced a dilemma between the expectations of her as a mother and her potential in academia.

She chose to work and raise her children. “I was a dressmaker, a weaver,” Norrman says. “Suddenly one day with [my] kids, I said, ‘I'm going back to university.’ People just said, ‘No, you can't do that. You need to wait.’” Despite the naysayers, Norrman knew what was right for her. She chose to move to Boston in order to pursue a PhD from Harvard University. “I got accepted to [Harvard],” she says. “I received a full scholarship. Why should I say no?”

Upon earning her PhD in 2005, Norrman moved to Minneapolis to teach here at the University of Minnesota, where she continues to teach Swedish language and Scandinavian studies. In her research, she investigates her passion and curiosity: women in history.

The Role of Detective

Norrman recently took a semester’s leave from teaching and traveled to the Àrni Magnússon Institute at the University of Iceland. “I spent three months there during the fall of 2019 in the manuscript department,” she says. “I didn't have a clear plan when I came in. I just started to read.”

What she read was the Sturlunga Saga, a manuscript of Icelandic sagas detailing a period of political instability in the 13th century. Norrman worked with the translated version of the work as well as the original piece in Icelandic, which, despite its age and value, she was able to hold and analyze. In doing so, Norrman found she was interested not in the main focus of the narrative, but in what was written between the lines.

The stories revolved around men, but brief stories of women and their roles in society emerged from side notes. “There is not one long text about women but in the passages, I did find them.” For example, Norrman found a blurb about “a woman [who] takes off with her lover. Her husband knows about it, and he is not doing anything about it...Life just goes on.”

Stringing these marginalized stories together wasn’t straightforward. “I had to find these passages [about women] since [the stories] are from a male point of view. You have to kind of puzzle things together.” This desire to weave a story out of minor passages seems to have come from Norrman’s childhood. “When I grew up, I loved reading the Nancy Drew books, and this is kind of the same,” she says. “You have a clue, you need to follow the lead, and you have to really think.”

In order to find these female-focused stories, however, Norrman had to read through thousands of pages of content that didn’t pertain to women. “I think that is something I really would like people to know,” she says. “They can find these stories, but [they] have to browse through these enormous, long, long, long, long, long texts about [battles and war].”

Gendered Narratives in Historical Accounts

In the process of acting as a detective, Norrman observed the clear divide between the portrayals of gender in historical narratives. She notes that the authors of these manuscripts “didn't really think about women as being of importance.”

This observation motivated Norrman to compare how often women were mentioned in Icelandic histories versus the histories of other nations, like France and Germany. Unfortunately, Norrman didn’t find much on women, “but of course they were there, so why don't we read about them? But in [the Sturlunga Saga], we have them.”

Aside from how frequently women appear in texts, Norrman also found that the role of Icelandic women was different from that of women in European countries. “They had a more independent status, I would say,” she says. “They could declare themselves divorced.”

While historians have often portrayed women to be background characters, Norrman was able to identify the inaccuracy in doing so. “Women were strong. They had their own will; they had their own say,” she says. “They were not just merchandise to be married off for the purpose of securing an estate or inheritance. An Icelandic woman couldn't be handled that way.”

The Role of Women in Research

Norrman’s research uncovers the reality of the history of Icelandic women and the way they were portrayed in narratives written exclusively by men. Through this project, Norrman was able to express her curiosity for the unknown and her devotion to learning. “Life is fun. Academia is fun. Researching is fun. Exploring is fun,” she says.

Curiosity is Norrman’s driving purpose for doing the work she does. “I think when you research, you have to be curious.” she explains. “If you don't want to explore, you can't do all these things...I think that's who I am.”

This story was written by an undergraduate student in Backpack. Meet the team.