Transcontinental Graduate Seminar Investigates the Archival Process

Professors Leslie Morris (GNSD, Jewish Studies) and Mary Jo Maynes (History), have been investigating how records of the past are preserved, lost, and interpreted. Across three countries, their graduate seminar HIST 8025/GER 8820 encourages students to critically question archive records. This group of graduate students and faculty colleagues with varying disciplines dives deep into their specific interests for the final research project. The course is part of a research collaborative supported by the Center for German and European Studies.

A Deeper Look into the Past

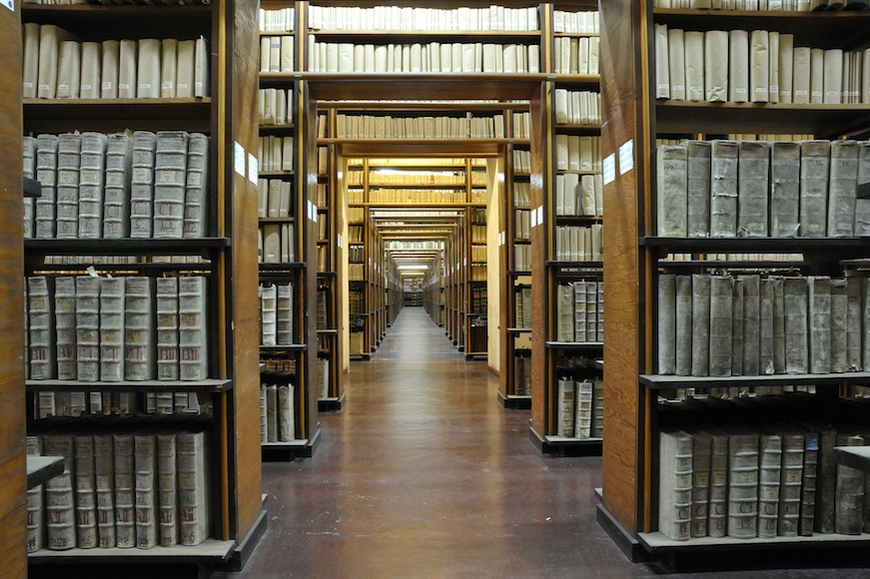

Archives hold traces of the past and help us to tell stories. By giving old documents, images, and objects spaces to exist, they serve as evidence of historical experiences and events. Historical memories preserve and contribute to a community's sense of identity while shaping understanding of cultures outside of our own. The problem is the selectivity of what is archived and what is not, which reflects past (and present) power relations. Examining the historical dynamics that have shaped archives of all sorts is what motivated Morris and Maynes to educate future historians to critically examine the sources about the past with which they come into contact.

The three universities, located in the Twin Cities; Helsinki, Finland; and Bochum, Germany, introduce students from a variety of disciplines to the idea of “interrogating the archive." The course asks students to develop a critical eye for how historical information is preserved or lost, documented, and organized. It examines a diverse array of topics and approaches to many forms of preservation. Students come from a wide range of fields including history, public history and museum studies, literature and cultural studies, musicology, gender studies, and film studies to name a few.

Kathryn Huether, a PhD student in musicology, shares an old saying, “the more you learn, the less you realize you know,” which has forever changed how she engages with archives. The course taught her to consider the motivation behind an archive’s origin and format. “There are elements that contribute to the presentation and engagement with historical pieces that are not at first obviously clear," she explains.

The instructors draw on a few exemplary archives to provide hands-on experience that students can expand on for their research project, or they can pursue topics of their own devising. Because there's such a wide variety of sites of archival collection, the course focuses on just a few forms, including written personal narratives, oral history interviews, film, and political party archives. Each class takes advantage of local “sites of history” to critically examine how history is preserved, debated, or suppressed and to compare their experiences across borders. Observing urban spaces, historical commemoration, museums, traces of migration, and diaspora helps students understand how history is—or isn't—archived.

Student-Run Investigations

“We should never stop asking questions, and we should never assume we know or have the answer,” says Huether. The interdisciplinary course allows students to dive deep and question specific topics that resonate with them. Projects vary widely, from exploring meaning and representation in museums with a specific focus on the sound to collaborative source collection of a major US archive. One of the main foundations of the course teaches students to examine archival resources more critically and reevaluate the legitimacy of the information.

Sarah Pawlicki, a second-year graduate student in history, explains that she has gained a clearer understanding of the inherent complexities of the field. For her, the biggest insight of the class is discovering the unconscious power dynamics that come with working with different types of sources. “So far, my biggest takeaway has been a newfound appreciation of form and style, as well as content, in the context of historical sources,” she explains. “Thinking critically about what types of information are captured in, for example, an oral history as opposed to a letter, and how the dynamics of power shape form and style throughout the sources in question, has been enlightening for me.”

Pawlicki’s research paper highlights the usage of funeral and pastoral elegies as a means of teaching, often a moral lesson. She is investigating the way Puritan elegies memorialized specific individuals, while at the same time reinforcing social, especially religious, values to the community and encouraged them to follow the deceased’s example. It reveals how memory can be used for communal values and comradery, and Pawlicki believes that memorials still follow this general dynamic today.

George Dalbo, a PhD candidate in social studies education, explains that the coursework influenced his approach to both his personal research and dissertation. His focus is on how faculty and students understand mass human rights violations, such as the Holocaust and genocide, and how those topics are presented across social science curriculums.

The course introduced a new cultural dimension to the way Dalbo thinks about archives. Now, he asks questions analyzing how curricula are created and the representation of Indigenous people under a Western lens. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, specifically the History Unfolded project, piqued Dalbo’s interest and became the focus of his research. The project asked middle and high school students to submit newspaper articles that covered aspects of the Holocaust from local newspapers to challenge the myth that Americans didn’t know about the Holocaust until after concentration camps liberation in 1945. He’s interested in studying the archive itself, the steps taken to create the archive, and how it ties back to the classroom.

Continuing Collaboration

The class “enhanced my ability to assess my own research and provided the resources to ‘read against the grain,’” says Pawlicki. She appreciates the course for making her more aware of the pitfalls of common historian methodologies and more critical of information—including her own. She hopes people will think about how stories are curated, presented, and packaged.

Despite meeting across three separate classrooms thousands of miles apart, students have connected with their cross-collegiate peers via video to discuss and share their knowledge. As the fall seminar wraps up, students are encouraged to submit their research papers investigating archives for a special research workshop to be held (pending funding) in Spring 2019 at the University of Minnesota. The conference will provide an opportunity for students to connect with international classmates and display their contributions to the research community.

This story was written by an undergraduate student in CLA.