‘It’s Been Setting in on Me That This Is Like a Cycle’

The events of 2020 carry painful resonances for black families, whose collective memories of violence reach back generations.

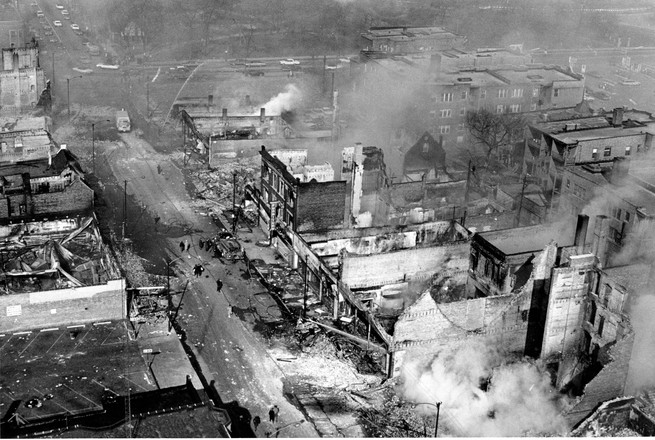

Roger Williams Jr. was 10 years old when Martin Luther King Jr. was killed. It was 1968, and the assassination prompted chaos, uprisings, and fires across the country, including in his own Chicago neighborhood. “At the time, as a kid, you didn’t understand it,” Williams, now 62, told me.

More than 50 years later, “the faces have changed, but the policy is the same,” he said, referring to the killing of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minneapolis late last month. “I thought things would get better.”

Williams is one of the many, many black Americans for whom the events of 2020 carry painful resonances, whose collective family memories of previous violence against black people reach back generations. “This happened to Dad, this happened to Grandpa, this happened to Great Grandma,” is how Saje Mathieu, a historian at the University of Minnesota, described to me the pain and frustration families feel upon witnessing still more injustice.

“I think that that’s what some people are having a hard time understanding,” Mathieu said. “They [might think] that it’s only about what happened [very recently], instead of understanding that these are triggers that happen at intervals that for some people feel like they’re at the rate of contractions [during labor]—like every three months, there’s something happening.”

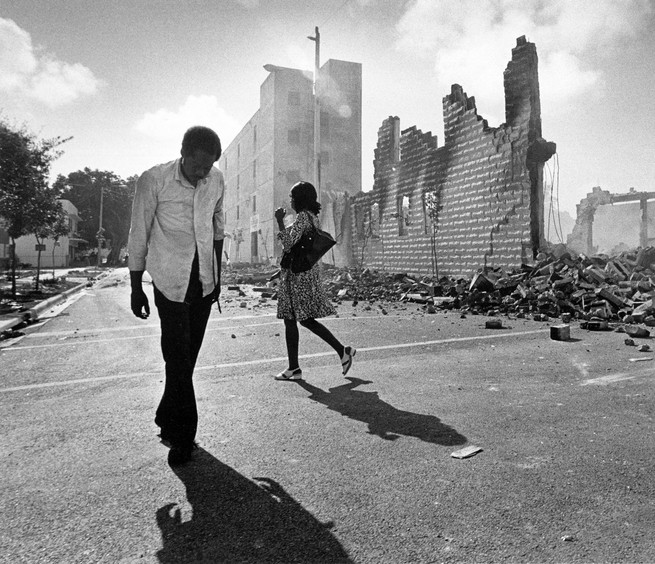

One of those contractions took place some 40 years ago and was centered on the death of a young insurance agent in Miami named Arthur McDuffie. In December 1979, police chased McDuffie after a traffic violation, and once they stopped him, a group of them beat him with their flashlights and nightsticks, putting him into a coma and ultimately killing him. At the time, a county medical examiner said his skull had been “cracked like an egg.”

Six months later, when four white officers involved in McDuffie’s death were found not guilty by an all-white jury, thousands of Miamians took to the streets, sparking unrest that led to 18 deaths. Jerry Rushin, a longtime Miami resident and a friend of McDuffie’s who was 33 at the time, told me about two images from the uprising that he remembers vividly. One was a young man who came into the office of the radio station Rushin managed, his face and shirt covered in blood, asking for help. The other was the sight of the neighborhood burning, as viewed from above during a helicopter ride Rushin took with a local official. “It’s like we had just hit a village or something in Vietnam—I’d seen it so many times a few years before when I was in ’Nam,” he said, referring to his stint as a combat medic.

Rushin made a point of telling his three daughters, all of them now adults, about what he’d seen. “You’ve got to know what happened to know what’s really going on,” he told me. “I want them [to see] the whole gamut of being a black person in America, the good and the bad.”

His youngest daughter, Shellany Rushin, wasn’t yet born when the McDuffie verdict came down. And in the early 1990s, when she saw white police officers in Los Angeles beating Rodney King on TV, she was only about 5 years old—too young to have “whole gamut” conversations. “I was in that age group where you’re learning about community helpers, and how police officers are great,” she recalls. “And then you watch this video of them literally beating a man. I didn’t really understand any racial aspect of it, but I do remember saying to myself, Well, those aren’t good people. Those aren’t helpers if they’re hurting this man.”

“It’s been a tough week,” she said, when I asked her recently about how she’s coping with the death of George Floyd. “I remember going through this a few years ago after the killings of Philando Castile and Mike Brown … I guess this week, it’s been setting in on me that this is like a cycle: An injustice happens, we protest, we stop protesting, and then a little while later, it happens again.”

This cycle has played out over multiple generations of her family. “When the McDuffie riots happened here in Miami, my father was 33. I’m 33 [now]. And my grandparents, they told me they never participated in any of the protesting and the riots, but they told me they watched it from a distance. Three generations—at least—of my family have witnessed the same thing.”

Williams, the Chicago resident, felt a similar despair. His oldest grandchild is 11—roughly the same age he was when King was assassinated. Recently, he told me, he tried to think through how he’d react if a police officer pulled him over and threatened him with his grandkids in the car—would it be wiser to set the example of appeasing the cop or of pushing back? “The scary thing about that is, I didn’t come up with any conclusion,” he said. “If you went about it either way, the cop still has the upper hand.” Williams told me he’s at a loss about how to advise the generation of black children growing up now.

Although so much of the frustration over Floyd’s death feels upsettingly familiar, the people I spoke with told me the current protests seem to break with the past in some hopeful ways. For one thing, protesters have already mobilized not just nationally, but globally. For another, those I interviewed noted, the protesters seem to be more diverse. Their supporters do too: “One of the big differences I’m noticing is hearing, seemingly for the first time, mayors, governors, police chiefs saying, ‘You’re right that this isn't right,’” Mathieu said. “That is in part what makes me feel hopeful as a historian.”

But even so, surveying the protests of the past half century, Mathieu told me, “I’m devastated to say that [protesters’ concerns] are exactly the same”: They’re resisting police brutality and “the senseless marshaling of state power,” and pursuing “equal access to good education,” “affordable living standards and affordable access to medical care,” and the “demilitarization of people’s homes and neighborhoods.” (She did note, however, that antiwar messaging, a feature of ’60s protests, has been absent from the current demonstrations.)

“Is it important that we’re saying the same words but to a different crowd, a more integrated crowd, a crowd that’s not going back to clearly segregated signage and housing?” Mathieu wondered. “Or is it more painful that it’s the same language with a world that seems to have changed the signs—the segregated signs have come down, but the lives remain segregated, whether it’s by class or by race or by citizen[ship] status? I’m not sure.”

Shellany Rushin also feels ambivalent. “Part of me hopes that this time is a little different,” she said. “But in the back of my mind, it also feels like the same thing—it feels like what I’ve heard my grandparents tell me about, what I’ve listened to my dad tell me about for years, and what I’ve seen before with my own eyes.”

It has her thinking about the next generation too. “My husband and I don't have children yet, but a conversation that we often have with each other is about what kind of world we would be bringing children into,” she told me. “And I would be lying if I said that these past instances didn’t affect how I frame that in my mind.”