We Have to Rely on Each Other

In this age of physical distancing during the time of COVID-19, it would be hard to think of a place more removed than the South Pole. Last year, Robert Miller (BA ‘91, political science) took part in an expedition to that far away point on our Earth, not for reasons of separation, but to experience and bring home a clarified message about the importance of understanding climate change impacts and how to create a sustainable world.

“Antarctica wants you dead, so every member of the expedition team has to do their job or we all die. It's completely visceral, you feel the cold seeping in and know if that tent isn't set up or snow isn't melted for warm water the dull pain in your toes and fingers will quickly turn to hypothermia and you'll die. The coronavirus also wants you dead, so the Pandemic is really an Antarctic expedition on a global scale. Everyone has to do their part or many will die,” Miller said.

A US Army veteran who led four successful startups during his career, today Miller operates Miller Companies, a private investment platform and holding company for his investments that invests in operating businesses and startups, particularly in the hospitality and technology spaces. The founder of Commonwealth Gaming, a nationwide operator of Video Gaming Terminals, Miller also holds an MBA from Columbia University and another from the University of California Berkeley.

Miller spoke to CLA about what drives him:

Why did you decide to take on this adventure?

Through my interest around recycled products, I learned about and was inspired by Robert Swan who was the first person to walk to both the North and South Poles. The more I heard about his 2041 Foundation Team, the more interested I became—Antarctica is 90 percent fresh water and home to species found nowhere else. More importantly, the ice is three miles thick on the continent. Built-up over millions of years, that ice is a record of our planet’s climate, and by drilling down into it we are given the single biggest key in understanding the climate crisis.

Talk more about the 2041 Foundation Team.

Swan founded the 2041 Foundation about 15 years ago for the study and preservation of Antarctica through the promotion of recycling, renewable energy, and sustainability to combat the effects of climate change. The fate of the continent will be decided by the year 2041 when the treaty governing its use expires. Everything about the expedition helped engage businesses and communities around climate science and putting sustainable practices and equipment to use.

Antarctica is one place where international countries are working together using science for peace and using science to protect the environment.

I am a pragmatic guy. I want to know about how a project truly makes a difference and what impact it has. And through the expedition, by actually making the journey, I could see it for myself, come back, and tell the story of what I saw. I’ve been there. The work is important. It’s in the harshest place in the world, and it is worth protecting.

More than two years ago, Swan tried to make the crossing with solar energy and biofuels for stoves. That trip ended for him when he injured his hip 300 miles from the pole. That’s why our expedition was named The Last 300. Swan was dropped at the mountains 300 miles from pole and out for two months when his new hip gave way with 40 miles to go. I joined the team for the Last Degree, 60 miles from the South Pole. Swan is going back to finish those 40 miles in 2021.

It’s an arduous task. Even though the distance is only 60 nautical miles, the 9300 feet altitude makes it challenging. The Antarctic interior is different and important. There are the winds, 24 hours of daylight, and although not as picturesque as the penguins and icebergs of the coast, it is important.

What was involved in preparing for it?

A lot of training. To be ready for the three weeks of the expedition, I trained six days a week for 12 months—pulling tires recycled from a tire shop, walking around town in a harness pulling a sled loaded with 100 pounds of gear, and long-distance running and hiking with heavy 40 pound packs. And there was time spent in Norway where the logistics company trained the team in cross-country skiing. And we were outfitted with the best clothing from Norway where they have the best expertise in custom-designed gear for the extreme conditions.

How was the team selected?

The team was designed by Rob and his people. I was inspired by all of them. Our team leader was Johanna Davidson, who holds the current record for crossing Antarctica solo and unsupported. My tentmate was another inspiration. Cameron Kerr, like me, was an ROTC graduate and US Army officer. He lost his right leg to an IED while deployed in Afghanistan. He did what I did...but with a prosthetic leg.

Our international team also included Mary Nicholson and Ian Milbourn from the UK, Barney Swan (Rob’s son) from Australia, 19-year-old Berkeley student Paulina Villonga from Mexico City, John Foster from the US, seasoned arctic guide Kathinka Gyllenhammar, and filmmaker Kyle O’Donoghue representing South Africa and Norway.

What were some of the surprises you encountered during the journey?

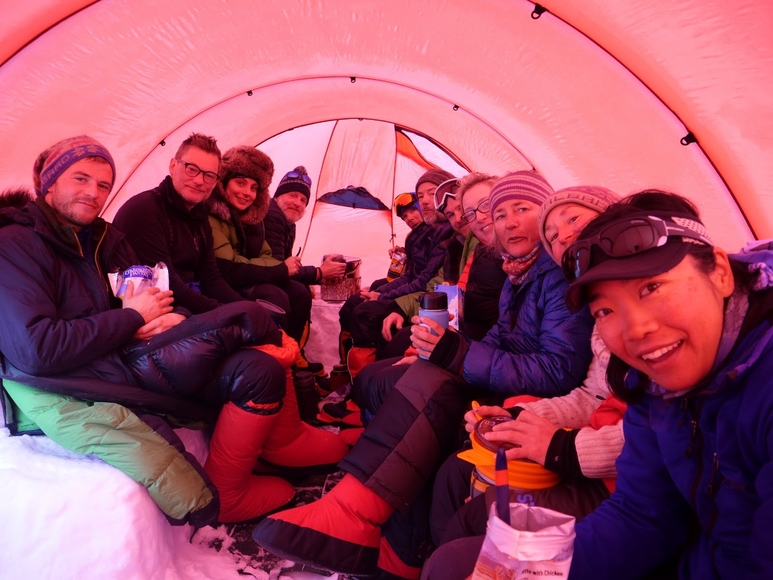

There is a picture of our base camp not long after we were dropped off that captures a bit of what it felt like—there we were, together—at 89 degrees south latitude, feeling as if we were surrounded by 360 degrees of ice and sky, just 12 people sharing a feeling of utter smallness. The place is so vast and you are a small part of it, and we have to rely on each other to succeed. Our international group knew we had to put aside whatever our differences were so that no one would die, so that we all could get to the pole.

We were not at all like-minded. We took an extra tent to dine in for breakfast and dinner, and over our re-hydrated meals, we’d chat. We were from a lot of different places and backgrounds—the military, an idealistic 19-year-old, an Oxford-educated London executive terrified by Brexit. And all of us are strongly concerned about our globally connected world. We were all there not just to protect Antarctica, but also for the physical and personal challenge. Every day was an acute reminder of Sir Edmund Hillary’s line, “it’s not the mountain we conquer, it's ourselves.”

We were aware of how we needed each other to survive. Evacuation was three to four hours away. You make a mistake, rip a tent, and the entire team is in jeopardy. You can’t focus on just yourself.

There's a picture of you holding the University of Minnesota flag at the South Pole. What's the story behind that?

I had always planned on that. That was a pivotal moment and I wanted to commemorate it with things important to me.

The University of Minnesota was personally and professionally important to me. I met my wife Amanda of 27 years there...in a political science class. I don’t remember much about the class, Political Thought in America in Anderson Hall, but I remember meeting her. My friends from that time are my friends now. The U was an amazing world of people and ideas I’d never experienced growing up in South Dakota. It was where I started my military career. My liberal arts education ultimately led to an interest in business, and when I think of it, it led me to the South Pole. It’s where I got interested in trying new things.

What did it feel like when Robert Swan ultimately didn’t make it to the South Pole again on the Last 300 trek?

Rob is a force of nature; he never gives up. This was his chance to return to best Antartica after the continent beat him last time. Unfortunately, his hip had other ideas. Once we knew he was safely evacuated, we had to re-focus on the mission. Remember, Antarctica wants you dead, so we had to continue the mission together. Rob was adamant that we reach the pole with or without him.

We continued on and got to the pole on a sunny day at 2:00pm Chilean time. It was perfect. We spent five hours there before getting picked up and returned to base camp.

What was the worst thing about the journey?

The time away. Even before the trip itself, the training weekends were brutal. Two and three to four hours of daily training when I could have been with family. And during the trip there was no internet...there was for the scientists...but not the expedition members, so I couldn’t communicate with family or work except by short text messages by satellite communicator.

What would you tell your younger self as he was just coming to the University?

Ultimately, I’d tell my younger self, “You can do it.” I think coming from Pierre, South Dakota, and just being young in general, I had a lot of worries, thinking maybe I couldn’t make it in Minneapolis. I hadn’t ever ridden on public transit before...I didn't know how to navigate that. I was aware of being among incredibly smart kids and not sure I could keep up.

I was lucky to be a part of the military and the ROTC Golden Gopher Battalion during an era of peace. It helped me gain confidence mentally and physically. I learned how to be in the right place at the right time, with the right “uniform” and right attitude.

And from that, the belief that I could start a company and to follow my interests. For example, I was always interested in aviation. I had invested in a drone company and wanted to understand the pilots, so I became a pilot. It offered a mental challenge more than anything else and another personal challenge.

So yes, younger self, you can do it.

What is next?

I’m looking for my next adventure. And I need to share this story.

How about a trip to the North Pole?

I’m not sure. Maybe to reunite with the team on the south pole of the moon. Walking to the pole is a lot easier on the moon.