Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 17, No. 1 (2019)

Student Identity Disclosed: Analysis of an Online Student Profile Tool

Kirsten Jamsen

University of Minnesota–Twin Cities

kjamsen@umn.edu

Katie Levin

University of Minnesota–Twin Cities

kslevin@umn.edu

Kristen Nichols-Besel

Bethel University

nicho309@umn.edu

Abstract

In the University of Minnesota’s Student Writing Support program, we gather, record, and share student and course information in order to support consultants in their work with writers; to assess and improve our own practice; and to make compelling, data-driven arguments for the center’s continued existence. Recognizing moments when these data-collection practices worked against the relationships we wanted to build with student writers, we began to critique these practices, with the goal of creating more intentional criteria and methods for soliciting client information. In Fall 2013, we developed and introduced an online Student Profile tool where clients could indicate their preferred name, provide a guide to pronouncing their name, include their gender pronouns, list any language(s) they speak and/or write, and indicate anything else they would like our consultants to know about them as writers/learners. We have become particularly interested in what students choose to share about themselves in that last open-ended prompt: When we give students opportunities to disclose aspects of their identity, what do we learn about them and about how they construct their identities in the context of a writing consultation? In this article we share our analysis of client data we collected in 2016–17, which reveals students’ awareness of their identities as writers, students, and learners as well as the complexities of these identities in a writing center context. Our findings also speak to larger conversations about the ways student identities are constructed and created within higher education.

In the University of Minnesota’s Student Writing Support program, we formally gather, record, and share student and course information in order to support consultants in their work with writers; to assess and improve our own practice; and to make compelling, data-driven arguments for the center’s continued existence. Such institutional information-gathering is every writing center’s responsibility, as Neal Lerner noted back in 1997 in his influential “Counting Beans and Making Beans Count” article in Writing Lab Newsletter, which helped initiate important conversations about how writing centers collect and use quantitative and qualitative data and what that data reveals. Work by Lerner, Noreen Lape, and Ellen Schendel and William Macauley offers writing center professionals frameworks for using such data to educate administrators about the value of our centers and to assess our progress towards particular educational outcomes. Rather than follow in this tradition, our close look at our own data here aligns with Lori Salem’s recent analysis of the academic and demographic characteristics of students who choose to use the writing center compared with those who do not. Like Salem, we are interested in looking at student choices—in our case, what writing center users tell us about themselves—and how “their choices can reveal how society shapes understanding of implicit ideas about writers, writing, and writing instruction” (150).

Since 2002, we had been gradually refining what student data we collected and shared—a practice made easier with the 2005 development of our own home-grown (and ever-evolving) appointment-making and scheduling tool. However, starting in 2010, we began asking ourselves some harder questions about our data-collecting methods and goals. In our efforts to say “yes” to consultant and administrator requests for information, and with our desire to gather up data, we sometimes forgot to ask ourselves critical questions: What if we don’t actually need to know this information? What if we are asking for this information in hurtful ways? And what if, in the questions that we ask or fail to ask, we are missing opportunities for affirming student agency? These critical questions arose for us in three moments.

Moment 1: An online consultant asks a director: “Is there any way we can see the student’s gender?”

With this request, one of the consultants who worked in our online, text-based version of Student Writing Support was suggesting that a new piece of information be displayed in our consulting interface. We commonly tweak our home-grown, web-based database, so it’s not unusual for anyone on staff to suggest a new feature. And using the logics of the university’s Data Warehouse, information on what the University listed as “student gender” would be easily available to us. For assessment and reporting purposes, our database system already pulled in University data associated with each student—full name, unique internet ID, unique student ID, college, and major —and all consultants could read this information when they pulled up the record of a writer with whom they were going to meet. Names, internet IDs, and student IDs were all tools to help consultants and front desk attendants create appointments for the correct person. College and major information not only was useful for reporting, but making it visible for all consultants also gave them some initial context about how familiar the writer might be with the disciplinary expectations of the field for which they were writing.

This consultant explained that they felt more comfortable “knowing” what a client’s gender was—something they explained they struggled with online in the absence of visual cues, and without a sense of what genders were associated with common names in non–Romance languages. Of course, there is no way anyone can see gender: gender expression and gender identity are two separate things, and it is not possible to see or know someone’s gender identity by reading the visual cues of their gender presentation. But in 2010, as cisgender women who were not yet even attuned to the idea of cisness, and as leaders who welcomed suggestions about center technologies and practices, we charged ahead, pulling the “M” or “F” associated with each student from the data warehouse into our SWS.online interface for consultants. (Revealingly, that we included the gender label only in the SWS.online interface underscored our ciscentric/transphobic belief that it was possible for consultants to make correct assumptions about gender in face-to-face contexts.)

Moment 2: A front desk attendant apologetically informs an arriving client, “The system is asking me: what is your first language?”

Besides gathering student information silently and automatically from Data Warehouse, we also required that every writer provide several pieces of information: What course, if any, are you writing for? What kind of project are you working on? and What stage are you at—brainstorming? Early draft? Later draft? We required this information believing that the consultant would find it useful in framing the session and developing a manageable agenda relative to the project’s due date. These questions were easy for writers to fill out online and for attendants to ask in person. However, we also asked another, harder question of every first-time visitor: What is your first language?

Not only did we see this question as a way to give consultants some early information about the specific English-language-learning challenges that a writer from a particular language background might face, but it also allowed us to report to University administrators about “language diversity”—which, given the high population of writers whose primary home language was Mandarin, Korean, Somali, or Hmong, could also be an indirect way of highlighting racial and ethnic diversity. Asking the language question usually fell to the front desk attendant, who greeted writers as they arrived, and who—because an answer was required before they could check a writer in for their consultation—sometimes had to supplement this information if the writer had not included it when they made their reservation online. These moments were awkward for front desk attendants and clients alike. Attendants recognized the ways this question invoked assumptions about language, race/ethnicity, and nation, and client reactions ranged from puzzled to embarrassed to insulted.¹ Accordingly, attendants would often shift responsibility for this question—and only for this question—to the database: “The system is asking me for a first language.”

Moment 3: A writer reminds a consultant for at least the fifth time: “Call me Fran.”

Just as Data Warehouse can hold inaccurate information about gender identity, so can it fail to provide the names that students wish to be called. For trans and gender-nonconforming students who have replaced their birth name with one that aligns more closely with their identity—especially when the birth name and the replacement name carry very different cultural cues about gender identity—being called by their birth name from Data Warehouse can be profoundly disturbing, even traumatic. It can also put them at risk for violence from others. For both cis and trans/gender-nonconforming writers whose birth names might not be intelligible or familiar to monolingual (read: white English-speaking American) readers, interactions with writing center staff can also be fraught with misidentification and othering. When a member of a powerful group mispronounces or misremembers the name of a person from a minoritized group (including people of color, immigrants, non-US citizens), that person experiences a microaggression (Kohli and Solórzano). One particular writer, an undergraduate student from China, wanted us to call them by their English name, Fran, rather than the Chinese name listed in University systems. A frequent user of the Center, Fran was always greeted by their Chinese name as listed in our database; Fran had to ask consultants to use their preferred name in almost every visit, even when previous visit comments began with a reminder for the consultant to call the writer “Fran.” We were failing in our responsibility to use the name each writer preferred, and, whatever name they preferred, to pronounce it correctly.

Moments like these showed us that (1) we had work to do around our tendency to make assumptions about people’s identities—assumptions which were underscored by the kinds of questions we did or did not ask; (2) we were creating unproductive discomfort for students around core elements of their identities; and (3) students wanted us to know parts of their identities that our system did not recognize.

Because each of the three moments above is about (dis)comfort in some way, we pause here to include an important caveat about the issue of “comfort.” With Jackie Grutsch McKinney, we recognize that the grand narrative of writing centers as “cozy homes” inscribes a limited (white) raced, (middle) classed space that is comfortable only for some. As many critical race scholars have pointed out, “comfort” does not always mean safety, particularly for people of color—indeed, much of white supremacy is based on ensuring white people’s comfort at the expense of the wellbeing of people of color (Shih).

We want to reconsider comfort in a writing center, particularly when that comfort comes at the expense of people with marginalized identities. After all, consultants should feel “uncomfortable” making assumptions about writers’ gender identity. Front desk attendants should feel uncomfortable asking questions about language that appear to position whiteness as the norm.² And consultants should feel uncomfortable taking for granted that the larger university systems of naming can speak for students better than the students themselves can. Whose comfort was being prioritized in our Center? And at whose expense? In other words, thinking institutionally and interpersonally, what did it mean for us to ask writers for any kind of identity-related information at the beginning of our interactions? And what did it mean that language was the only identity-related information we officially recorded?

On one level, an initial request for information is part of institutional discourse (Agar)—the conversational structure between an institutional representative and a client of that institution. Institutional discourse encounters always begin with a “diagnosis,” when the institutional representative (in our case, the front desk attendant, the writing consultant, or both) seeks information from the client to make sense of them as a client: how do they fit within the structure and purpose of the institution? Requiring an answer to this one question about identity implied that language background (read: “English” versus “not English”) was the only element of student identity that was officially meaningful to us. Further, the question itself—“what is your first language?”—failed to recognize or value students’ multilingualism.³

The type of information requested, then, reveals how the institution sees the client; at the moment of request, the client is asked to see themself through that same frame—for example, as a non-native speaker of English. Because of the complex system of stereotypes related to language ability, writing ability, help-seeking, and who “belongs” in a PWI like ours, questions about language identity can function as microaggressions; in an institutional context, they can also trigger stereotype threat: “a disruptive psychological state that people experience when they feel at risk for confirming a negative stereotype associated with their social identity” (Aronson et al. 50). Although eliminating a question about first language would not prevent the real possibility of stereotype threat, we know that language identity is one characteristic associated with “ability stereotypes” (51) in a university setting, and that, therefore, questions about it can be a strong contributor to stereotype threat.

Description of the Student Profile Tool

With these theories in mind, in 2013, we began developing a new tool within our writing center scheduling and record-keeping application, accessible both by the consultant through our internal interface and by the student through the personal online portal by which they make and track their own appointments. Using this Student Profile tool, students had options to indicate their preferred name/nickname, provide a guide to pronouncing their name, include their gender pronouns of reference, list any language(s) they speak and/or write, and add text indicating anything else they would like our consultants to know about them as writers/learners. Later, thinking about the accessibility of our online consulting interface, we added a text field for students to indicate anything they would like consultants to know about their ability to perceive color or any accommodations needed when using standard Google Doc highlighting or commenting features. Each field of the Profile includes a mouse-over tooltip that explains why we are making space for this information or offers examples of what kinds of information students might wish to include. (See Appendix, Figure 1 and Table 1, “Student Profile with Explanatory Tooltips.”)

Students have had access to the Student Profile tool since September 2013, and they can edit, delete, or add information whenever they would like. We were pleasantly surprised that many student clients found the tool and started using it even before we publicized it because, for us, the Student Profile tool was built to enact our commitment to student agency, student individuality, student privacy, and the fullness of their identities, which we recognize can shift and change. The tool is also about consent, since students have the choice of whether they want to give us information and can determine what pronouns or names are used to describe them in our system. For example, a student who lists a preferred name will see the preferred name appear in the online chat interface, and a student who lists pronouns will have reduced their risk of being misgendered in our post-consultation records. Although we initially made the Student Profile editable by both the student client and the consultant (in case a student wanted the consultant to add information to the Student Profile during the consultation), we decided that only the student interface should be editable, leaving the consultant interface as read-only—both to reduce students feeling pressured to make changes in the moment and as a firmer commitment to student agency and consent. We hope that the Profile helps us be more aware of students’ need to be recognized how they want to be (e.g., “Call me Fran”), not necessarily how they have been defined by the institution, and to not make assumptions about the complexities of their identities as writers and human beings.

We became particularly interested in looking at the Student Profile data for what it reveals about what students think is relevant for the writing center to know about them, so starting at the end of academic year 2015–16, we ran a query on the Student Profile data of each year’s student clients. For this article, we focus on 2016–17 data because we became more certain of our methods of analysis after adding a third team member, and when we began this article in Spring 2017, that was our most recent data set. We wondered: When we give students opportunities to disclose aspects of their identity, what do we learn about them and about how they construct their identities in the context of a writing consultation?

Description of Profile Users

In the 2016–17 academic year, 13% of our clients (382 distinct students) included information in some part of their Student Profile. Most Profile users (91%) indicated a preferred name. In addition, 43% of Profile users indicated a name pronunciation, and 62% indicated their gender pronouns. Only 4% of Profile users (14 students) indicated online preferences.

To protect individual student anonymity, we queried only whether Profile users indicated a language and the total number of languages per student; the 2016–17 data revealed that 65% of Profile users indicated at least one language, with the highest number of languages listed as five. Based on earlier data collection in our center, the most common languages chosen among the over 125 language possibilities include English, Mandarin, Korean, Somali, and Hmong.

The open-ended prompt asking students to share anything else they would like our consultants to know about them as writers/learners (what we here call the “About me” data) had text from 26% of Profile users. Because this prompt gives students the opportunity to tell us about aspects of their identity they want consultants to know, we were interested to learn what they chose to include. We were especially eager to analyze what those inclusions revealed about both how they characterized themselves and what they thought we needed to know about them.

Methods

Our methods for analysis of the qualitative “About me” data were inductive in that we let the themes emerge from the data, and iterative in that we made multiple passes through the data before settling on the codes described in the next section (Patton).

The first year of data we analyzed was from 2015–16. Our first step was to move all the text in the “About me” box from our Student Profile tool into a Word document so we could see all of the data at once. In our first pass, we asked, what are the identities students are choosing to disclose? This first pass was completed separately by two of our team members, and we met to discuss our initial codes. From sharing our individually-generated code names, we developed 12 codes, which we saw as falling into three overarching themes: “Who am I?”; “What might we do together?”; and Other. We agreed that in many cases, the material in a given “About me” entry contained text that was complex, requiring us to divide the text into chunks, each explained by a distinct code. For example, the “About me” entry below was divided into multiple text chunks [followed by the code assigned]:

“I am transfer a student in 2015 fall. [student identity] So my english writing and speaking is not good. [writer identity] I can talk in a low speed. Would you mind to talk to me in a low speed. [type of help desired] Plus, I am struggle with my grammar [writer identity], can you help me how to develop the grammar? [type of help desired] Thank you so much! [appreciation]”

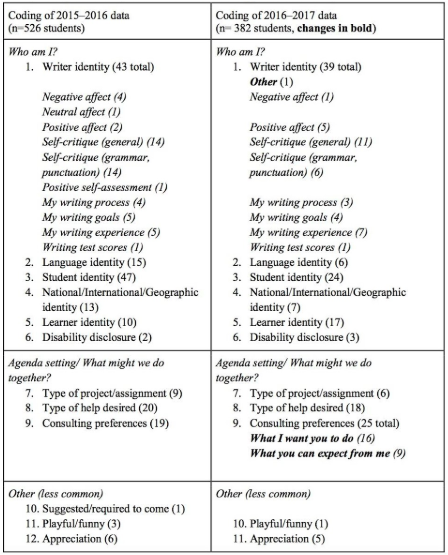

In this example and throughout our coding, no one phrase received more than one code (see Appendix Table 2, “Development of Codes over Two Sets of Data,” for the complete list of themes, codes, and subcodes).

We then did a second pass through the data to determine the degree to which these 12 codes fully described the data. This second pass verified that the 12 codes were sufficient, and we found that with just a few exceptions, we were able to apply them consistently, even when doing the coding separately. For any discrepancies in our coding, we talked through our reasoning and came to a consensus on which codes should represent the specific data.

Our third step was to look at all the data within a given code to see if the data that had been assigned to the same code was accurately represented by that code, or if the data revealed further distinctions. This work led to resolving additional minor coding discrepancies, but more importantly helped us notice the nuances within each “About me” entry, in which different words and phrases were best explained by different codes.

At this point, we determined that our Writer Identity code needed to be subdivided to more accurately explain the data. Our fourth and final step, then, was to go through the data we had already included under the Writer Identity code and develop subcodes. We started with our initial insights—that much of the data seemed to be divided into comments about grammar, anxiety about writing, and attitude toward writing. As we worked through each piece of data together, we determined that we needed more descriptive subcodes and more of them. For instance, in the following example that was also used above, the phrases initially identified as “writer identity” have the additional subcodes “self-critique (general)” and “self-critique (grammar, punctuation)”:

“I am transfer a student in 2015 fall. [student identity] So my english writing and speaking is not good. [writer identity—self-critique (general)] I can talk in a low speed. Would you mind to talk to me in a low speed. [type of help desired] Plus, I am struggle with my grammar [writer identity—self-critique (grammar, punctuation)], can you help me how to develop the grammar? [type of help desired] Thank you so much! [appreciation]”

Through a process of joint coding and conversation, we came up with 10 subcodes for the Writer Identity code (see Appendix, Table 2).

We applied these 12 codes and 10 subcodes generated during analysis of data from 2015–16 to analyze the 2016–17 “About me” data. The third team member joined the first two to lend another perspective, particularly as someone who had not analyzed the previous year’s data and so could apply the codes and subcodes with fresh eyes. As in our 2015–16 coding, we each coded separately and then came together to compare coding and work through any differences. Our process revealed that 11 of the 12 codes still accurately represented the data; we removed the code Suggested/Required to Come as no students in 2016–17 indicated this. Additionally, we added one subcode for Writer Identity: Other; and removed two subcodes that did not appear in the 2016–17 data: Neutral Affect and Positive Self-Assessment. Finally, we added two subcodes to Consulting Preferences: “What I want you to do” and “What you can expect from me.” (See Appendix, Table 2 for a complete list of themes, codes, and subcodes, and the corresponding number of responses for each.)

Findings

As seen in Appendix, Table 2 for the 2016–17 data, the most common types of information that students provided, based on the number of times the code appeared in the data, are described by the following codes: Writer Identity, Consulting Preferences, Student Identity, Type of Help Desired, and Learner Identity. What follows is a discussion of these codes organized by the themes in which we grouped them.

Theme: Who am I?

In their “About me” text boxes, students most often wrote about what we’ve labeled Writer Identity. This code encompasses student comments related to their writing process, specific problems or challenges they face when writing, their attitudes towards writing, and self-assessment of their writing abilities. Comments from students include the following:

“Really want to increase writing skills, afraid to write individual report.”

“I would consider myself an average writer. I struggle with grammar and proper use of APA formatting for research papers.”

“I’m not a very good writer.”

“I am not good at logical transitions and connections between sentences and paragraphs. I also want to make my writing read more natural.”

“I have practiced in my field for years and so have a lot of lived experiences which seem to influence my writing...”

In these comments alone, many aspects of writer identity are shared: goals, fears, assessments of their writing abilities, difficulties they face, and past experiences. These comments reveal a breadth of ideas students shared relating to their writer identities, but the most common type of comment was self-critique. Students in our sample were quick to point out their failings as writers. As writing consultants, we were not particularly surprised by this focus on self-critique; often in sessions, students focus on what they consider to be their weaknesses as writers, and the feedback they receive from teachers often identifies failings in their written work.

The next most common type of information related to identity had to do with student major, year in school, undergraduate vs. graduate student status—all of which are commonly discussed labels among university students:

“I’m a Freshman, major in nutrition.”

“I am economics major”

“New public health grad student for January 2016. … Out of school since 2008.”

It’s possible that providing this information was automatic for many students, given the many places in higher education institutions where students are required to identify themselves in this way. Indeed, if any clients had read the online biographies of our writing consultants, they would have seen similar information about program or major and year in school provided by the consultants themselves.

Many students also indicated what we called their Learner Identity, where they stated their learning style(s) and/or a description of the ways in which they learn best:

“I am a multi-modal learner. I have to see it, hear it, write it, read it, and think about it, and this makes me a slower learner.”

“I am a visual learner and find examples the most helpful to explain anything.”

These responses were likely prompted by the explanatory tooltip next to the “About me” text field: “If you know that you are a visual learner, for instance, or that you like consultants to take notes for you when you talk, this is a great place for you to tell us that.” The prevalence of discussions about learning styles and universal design on our campus may also contribute to this calling out of Learner Identity.

Theme: Agenda setting/What might we do together?

Second to Writer Identity (and also likely prompted by the above tooltip) was Consulting Preferences, which included what writers wanted from the consultants as well as how they would contribute to the sessions or what consultants could expect from them:

“I don’t want consultants to feel like they have to hold back on comments because they sound too harsh. I love any and all criticism and for people to tell it like it is.”

“I mostly just need someone to listen to me babble about my ideas”

“Complex thesis topic - sorting it out one consult at a time.”

“It helps to write with someone during sessions to get started. Encouragement and positive reinforcement helps me a lot; to be reminded that this is totally do-able and that I’m completely capable of doing this.”

As can be seen by the above comments, students were not only asking for procedural help but also emotional support. Emotional support is a key part of our consulting practices, and some of our writers acknowledge this in their comments.

Finally, a number of students were specific about the Type of Help Desired. They added ideas such as:

“I struggle with grammar and proper use of APA formatting for research papers.”

“I am looking for help ensuring I have presented complete arguments/viewpoints in my writing AND I am looking for assistance with formatting references.”

The fact that students included specific information about what they wanted to work on during a given consultation made sense to us since, presumably, that was one reason they were coming to Student Writing Support: to seek specific feedback from a writing consultant on their individual writing concerns.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our analysis of students’ responses in the “About me” field reveals students’ awareness of their identities as writers, students, and learners as well as the complexities of these identities in the context of visiting a writing center. We were not surprised that students chose to focus on these identities, but the ways in which they did so continues to challenge our ideas and assumptions about the students who visit our writing center. Additionally, we continue to question the types of information we gather and the ways in which we do so. However, the data we’ve gathered affirms for us the relevance of our Student Profile tool in showing how students understand themselves and their agency as writers and learners within our institution. Our findings also speak to larger conversations about the ways student identities are constructed and created within higher education, connections between identity and writing, and issues of rhetorical agency.

As our findings reveal, many of the students who wrote in the “About me” text box appear to be very aware of their own goals, concerns, and experiences related to writing and see that information as important to share. It is important to note that the 98 students who filled out the “About me” text box represent only 3% of our total student clientele that year; and that only 13% of our student clients put anything in the Student Profile, suggesting that many students are not aware of the tool or do not feel motivated to use it as part of their interactions with our online scheduling system. Yet, even with these small numbers, individual student responses push us to see students as complex individuals—so complex in fact that we needed to generate multiple codes and subcodes to capture what they chose to share.

Our work to look closely at how students are using the Student Profile and what aspects of their identities they chose to disclose has also given us greater appreciation for the complex nature of student identities within an institution and culture that is continually classifying them and making assumptions about what aspects of their identity are relevant.

In her 1999 book Good Intentions, Nancy Grimm draws on Louis Althusser’s notion of “interpellation,” or “hailing,” that is, how ideology recruits and transforms individuals into subjects through everyday calling out of possible, seemingly natural, subject positions (174). Grimm encourages writing center scholars to pay attention to the ways that writing centers are complicit in the naturalizing of particular identities:

Many teachers, students, and writing center tutors respond to institutional hailing by readily assuming the positions constructed by the institution. Because we see others in the institution respond in similar fashion to interpellation and because we are rewarded for assuming certain positions, we come to accept this process as normal—even good. (70)

In our writing center, those normalized positions might be, for example, Struggling Student, Expert Writer, Person Needing Help, and Responsible Tutor. Implicit in these positions is a sense of academic hierarchy, with tutors having more knowledge, responsibility, and power than their student clients but less so than faculty because they are positioned institutionally, as Muriel Harris notes, “somewhere between teachers and students” (37).

Such normalized identities also help institutions maintain and exercise power, as Pierre Bourdieu argues in his discussion of the “classification struggle” (482). According to Bourdieu, producing classificatory data is a way of exercising power in larger social structures because classificatory concepts create groups—think, for instance, of “native speakers” and “non-native speakers”—who struggle for power. By reducing people to specific group identities, such classifications ignore other salient aspects of identity, establish hierarchies between the groups, and maintain inequitable and oppressive systems. In their analysis of writing center mission statements, Erica Cirillo-McCarthy, Celeste Del Russo, and Elizabeth Leahy note that the “practice of siloing students based on perceived linguistic abilities” ignores linguistic diversity, often conflates language use with immigration status and other identity markers, and “fit[s] too neatly within the narratives of deficit discourse” (68). Deficit discourse suggests that students’ identities are problems rather than resources, and that these students need to be remediated. If students are viewed as needing to be remediated, the hierarchy between student and tutor becomes more pronounced, and the student has less power, or perceived power, in the consultation.

Although all students who visit the writing center must, to some degree, face the basic stigma associated with being A Person Seeking Help, students from one or more marginalized identities face actual micro- and macro-aggressions related to race, class, nation, language, ability, gender, ethnicity, and so on. Writing centers have become more aware of their own role in mitigating these aggressions, as Jacob Herrmann noted in his discussion of the need for “brave/r spaces” for LGBTQ+ writing center clients: “These students need to feel safe from negative repercussions based on their gender and sexual identity. They need to feel welcomed within the writing center, while also having a space in which to discuss and develop their writing and personal writerly identity.” Similarly, in their discussion of stereotype threat in healthcare settings, Aronson et al. suggest that attending to “a patient’s individuality and strengths” could help disconfirm the relevance of stereotype threat (54). Further, Mary C. Murphy and Valerie Jones Taylor suggest that a critical mass of “identity-safe” or “identity-affirming cues” (26) in academic settings could reduce stereotype threat. Given the importance of supporting individual identities within an institutional setting, then, we wonder if our optional and editable Student Profile tool could be one way of reducing such threats, as well.

It is our hope that with the Student Profile tool’s being open to what students want to disclose as well as being editable whenever the student chooses to add, revise, or remove information, student users are offered a way to experience agency in identity-claiming. Students can share information about themselves beyond how the larger university data systems classify them, and this information can serve as a countermeasure to the identities associated with help-seeking and with what kinds of students belong in a university. Yet, as the many self-critiques writers include in the “About me” text box show, the tool still does not outweigh the power of institutional contexts where writing center clients are constructed—by themselves and by the larger legacy of schooling—as deficient, remedial, or in need of “fixing.”

This is not surprising, after all, since the Student Profile tool is designed and hosted by an institution: it determines which categories are relevant. Further, in many ways, it has moved up parts of the institutional discursive moment of diagnosis—"Who is the client? Why [are they] now in contact with the institution?” (Agar 149)—from an in-person interaction to a digital one. Although a digital interaction on the surface can feel more institutional and less personal, we hoped online access to the Student Profile would feel less coercive and grant students the privacy and time to consider their responses. Nevertheless, students are most likely to see the Profile and its prompts for information about their identity when they are already planning an institutional encounter (a writing consultation), and so are primed to think of the Profile as another arm of institutional power. Ideally, the information a student provides in the Profile could open up a conversation between the student and the writing consultant or allow the consultant to approach the initial interaction in a way that respects their claimed identity. For example, the consultant would call the student by their preferred name, pronounce their name correctly, use appropriate gender pronouns, and acknowledge the information they share in the “About me” text box.

That “About me” information is, in many ways, the most interesting element of the Profile, since it gives students an opportunity to claim and reveal aspects of their identity that they see as relevant for their interaction with the writing center, often in ways that surprise us. For example, one student wrote, “I’m a musician,” which did not fit into any of our codes (we ultimately classified it under a new Writer Identity subcode, Other). A few students have made jokes in the “About me” box like “I am horrible with commas,” (making sure to end the comment with a comma, not a period).

Even as writers have made the Student Profile tool their own, we recognize that the very act of putting text into the “About me” field can fix one’s identities in problematic ways. For instance, one student wrote, “I am freshman, and a foreign student, and I am still learning how to write essays, as I don’t know how to.” If this student does not revise their Profile, they will remain in our system as a first-year foreign student who does not know how to write. It is our hope that through experience in coursework, as well as visits to our writing center, this student will develop confidence in their ability to write essays. Yet this student’s statement marks a moment in time that has potentially been immortalized in our system. If a student’s Profile remains unchanged over time, our consultants may approach their interactions with misconceptions about what could happen. For example, this student’s response links their student identity with specific consultation goals: “I am a new PhD student and want to improve my writing skill. So, I’d like to meet regularly not for a specific writing assignment but for correcting overall writing pattern and style.” In this instance, improving writing skill might be the goal for as long as the student visits the writing center. But very shortly after writing this, the student will no longer be a “new PhD student.” Both of these students, as first-year undergrad and first-year PhD, imply that they are not already writers but are in need of instruction and correction; if they do not update their information, they risk freezing their identities in the Profile. Even the act of creating a data set we could study required us to set a date at the end of each academic year in which we would export the data to represent that year’s student clients, with no ability to know if what was written in their Profiles was what had been freshly edited or was unchanged since their first visit many years ago.

Yet, as Amy Burgess and Roz Ivanič note in their study of adult learners, writerly identities always shift through time, especially in interaction with readers:

Over time, possibilities for selfhood combine and recombine; new discoursal resources become available; and context-specific patterns of privileging shift. For example, writing may at one time be seen as something that is not done by members of a particular group on a vocational course; over time, however, values might change so that to be seen writing might become a marker of group membership, and taking on a literate identity might become highly admired as a marker of business acumen. Such a change, however, can only happen as a result of one of the group being seen writing, and what she writes being read by others who see it as holding out possibilities for selfhood to which they might aspire. (24)

If students take advantage of revising their Profile as their identities shift and change, then an online tool that accounts for writerly identity is uniquely poised to support writers as they are “seen writing”—a goal of any writing center.

To resist freezing an identity in the moment of disclosure, Stephanie Kerschbaum posits a more dialogic understanding of identity disclosure. Specifically, Kerschbaum asks us to “orient to difference as rhetorically negotiated through a process named here as marking difference” (619). This processual and dialogic approach to difference accounts for changes over time: “[I]t is with markers of difference that people create, display, and respond to changes in self and other and the perceived relations between them. To acknowledge individuals’ yet-to-be-ness is to maintain an openness to one’s own and others’ identities and to refuse to take identity markers as fixed” (626). In its current form, the Profile risks being a fixer, not a marker, of difference.

Accordingly, to acknowledge and respect the fluidity and complexity of student identities, we’ve determined one significant change we’d like to make to the Student Profile tool. We plan to incorporate a pop-up window to alert students to the tool the first time they access our system each semester and remind them that they have the ability to make changes to their Profile at any time. A reminder will hopefully serve to challenge the idea of fixed identity and to acknowledge, as Justin Hopkins describes in his account of the Franklin and Marshall College Writing Center’s policy of asking for gender pronouns, that student “choices may change between filling out the form and the session” (10). Most importantly, we hope regular encounters with the Student Profile will encourage students to exercise their agency throughout their development as writers who work with Student Writing Support.

Our good intentions, as Nancy Grimm reminds us, are not enough; this is ongoing work. No matter what new opportunities for agentive identification the Student Profile affords, the fact remains that the tool, the students, and the writing center all remain participants in and subject to larger systems. We would like to think that the tool we developed would also remind those of us who are (or who serve the interests of) white, cisgender, middle-class, (English) monolingual and/or any other number of intersecting powerful and “comfortable” identities in academia not to rest within the comfortable, whitely idea of what is the norm. Nonetheless, stereotype threat is always a risk in a PWI; misgendering is always a risk in a cis-centric culture. In isolation, the Student Profile tool cannot overcome larger institutional and structural systems of oppression—and may even reinforce those systems in some ways.

After all, the Profile’s very focus on individualism can reinforce problematic beliefs that struggles with writing are merely individual, not the symptoms of being in an oppressive system that requires people to write in a certain (white) way. Asao Inoue notes that one core characteristic of whiteness as a discourse is “the Individualized, Rational, Controlled Self,” where (among other things) “individuals have problems and solutions are individually-based; both success and failure are individual in nature; failure is individual and often seen as weakness” (147). Another way of looking at those “About me” responses by students, then, might be as responses to an institutional invitation to blame oneself for one’s own struggles with writing. In other words, we still have some work to do with the Profile—which individuals does it call out to? Which (raced, classed, gendered) individuals does it make space for? Which (raced, classed, gendered) audiences—that is, writing consultants—do clients imagine will read their Profile responses?

We recognize that the Profile is part of larger intentional and reflective work that needs to be done in our and other writing centers. We work to recruit, hire—and, crucially, learn from and retain—consultants of color, consultants with disabilities, consultants who are multilingual, consultants who are nonbinary. We work to disrupt the tendency to make assumptions about gender identity, whether by deliberately sharing gender pronouns (if any) in staff meetings, including pronouns (if any) on public-facing nametags, and developing instructional materials that deliberately deconstruct gender binaries (for example, we include singular they in our subject/verb agreement handout, and, among the typical resources on APA style and semicolons, we have an entire handout devoted to using nonbinary gender pronouns). We work to amplify the voices of people from marginalized or multiply marginalized identities, whether in assigned readings or in leadership positions. We also continue to make mistakes.

The conversations that arise, with both staff and clients, help us start to uncover, name, and discuss the contested intersections of identity, social location, power, and privilege that have always been there. Even as our institutional authority puts us in unequal power relations with clients, the porous space of the writing center is also an opportunity. We are, of course, subject to institutional constraints, but we who work in writing centers are also in a position to challenge the ways in which higher education constructs student and writerly identities. We can do this in our own daily work, including but not limited to tools like the Student Profile. We must intentionally create and expand space for clients to claim and express their own identities in and against the university.

Notes

When we became aware of some of the political and safety implications of the first language question, particularly for refugee students who had faced danger based on their language identity in their home countries, we took the baby step of including an “undisclosed” option in case writers did not wish to share a “first language.” However, when we asked this intake question in person, we never formalized the idea of saying “Would you like to share your first language?” Instead, we continued asking “What is your first language?”, forcing the writer to be the one to introduce the possibility of refusal—a difficult move for the less powerful person in the educational institution.

As Inoue points out, “language carries with it—through our judging of it—imaginary bodies that are hierarchized in our social world. We do this unconsciously. We cannot help this associating of racialized bodies with language practices” (139).

We thank Co-Director Jasmine Kar Tang for first sharing with us this important observation about our website and database, which she made when she was a writing consultant during her graduate program at UMN. That the Profile now gives students agency to identify their multiple languages acknowledges those languages as resources, as discussed in the growing body of writing center scholarship on multilingual writers, specifically Bobbi Olson’s “Rethinking Our Work with Multilingual Writers” (Praxis vol. 10, no. 2, 2013), Ben Rafoth’s Multilingual Writers and Writing Centers (Utah State University Press, 2015), and Shanti Bruce and Ben Rafoth’s Tutoring Second Language Writers (Utah State University Press, 2016).

Works Cited

Agar, Michael. “Institutional Discourse.” Text, vol. 5, no. 3, 1985, pp. 147–168.

Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.” Lenin and Philosophy, and Other Essays. Translated by Ben Brewster, Monthly Review Press, 1971, pp. 127–186.

Aronson, Joshua, et al. “Unhealthy Interactions: The Role of Stereotype Threat in Health Disparities.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 103, no. 1, 2013, pp. 50–56.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice, Routledge, 2010.

Burgess, Amy, and Roz Ivanič. “Writing and Being Written: Issues of Identity Across Timescales.” Written Communication, vol. 27, no. 2, 2010, pp. 228–255.

Cirillo-McCarthy, Erica, et al. “‘We Don’t Do That Here’: Calling Out Deficit Discourses in the Writing Center to Reframe Multilingual Graduate Support.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, 2016, pp. 62–71.

Grimm, Nancy Maloney. Good Intentions: Writing Center Work for Postmodern Times. Heinemann, 1999.

-----. “Rethinking Writing Center Work to Transform a System of Advantage Based on Race.” Writing Centers and the New Racism, edited by Laura Greenfield and Karen Rowan, Utah State UP, 2011, pp. 75–100.

Grutsch McKinney, Jackie. Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers. Utah State UP, 2013.

Harris, Muriel. “Talking in the Middle: Why Writers Need Writing Tutors.” College English, vol. 57, no. 1, 1995, pp. 27–42.

Hermann, Jacob. “Brave/r Spaces Vs. Safe Spaces for LGBTQ+ in the Writing Center: Theory and Practice at the University of Kansas.” The Peer Review, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017.

Hopkins, Justin B. “Preferred Pronouns in Writing Center Reports.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, 2018, pp. 9-11.

Inoue, Asao B. “Friday Plenary Address: Racism in Writing Programs and in the CWPA.” WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 40, no. 1, 2016, pp. 134-154.

Kerschbaum, Stephanie. “Avoiding the Difference Fixation: Identity Categories, Markers of Difference, and the Teaching of Writing.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 63, no. 4, 2012, pp. 616–644.

Kohli, Rita and Daniel G. Solórzano. “Teachers, Please Learn Our Names!: Racial Microaggressions and the K–12 Classroom.” Race Ethnicity and Education, vol. 15, no. 4, 2012, pp. 441–462.

Lape, Noreen. “The Worth of the Writing Center: Numbers, Value, Culture, and the Rhetoric of Budget Proposals.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, 2012.

Lerner, Neal. “Counting Beans and Making Beans Count.” Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 22, no. 1, 1997, pp. 1–3.

Murphy, Mary C., and Valerie Jones Taylor. “The Role of Situational Cues in Signaling and Maintaining Stereotype Threat.” Stereotype Threat: Theory, Process, and Application, edited by Michael Inzlicht and Toni Schmader, Oxford UP, 2012, pp. 17–33.

Patton, Michael Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed., Sage, 2002.

Salem, Lori. “Decisions… Decisions: Who Chooses to Use the Writing Center?” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 2, 2016, pp. 147–171.

Schendel, Ellen, and William J. Macauley. Building Writing Center Assessments that Matter. UP of Colorado, 2012.

Shih, David. “What Comfort Tells Us about Racism.” 1 Apr. 2015, professorshih.blogspot.com/2015/04/what-comfort-tells-us-about-racism.html.

Appendix

Figure 1: Student profile with explanatory tooltips. The figure below is the student view of the default Edit My Profile page, supplemented with all the explanatory tooltips. On the live site, each tooltip becomes visible only when the user hovers over the question mark to the left of each prompt.

Table 1: This table lists each Student Profile prompt and its associated explanatory tooltip.

Table 2: Development of codes over two sets of data. Themes, Codes, Sub-codes (number of times the code appeared in the data)