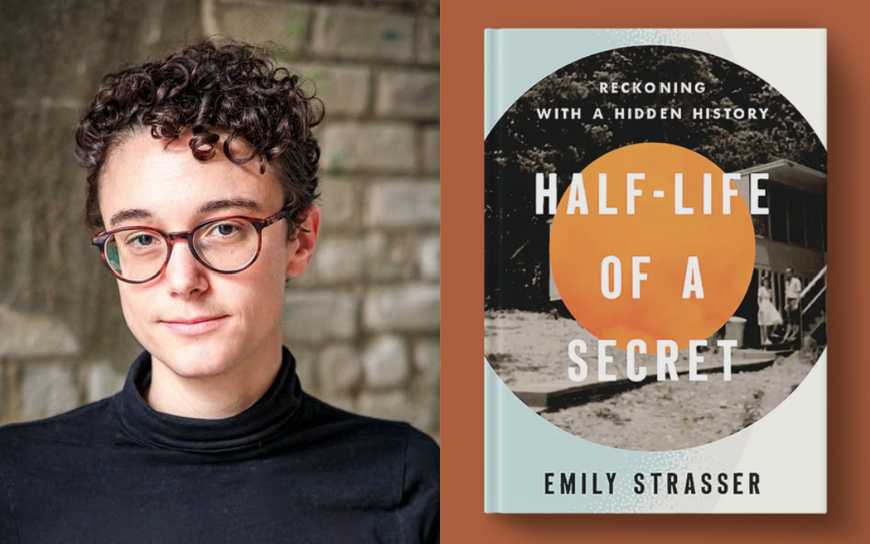

MFA Alum Spotlight Interview With Emily Strasser

In Emily Strasser’s debut book Half-Life of a Secret: Reckoning with a Hidden History, she delves into the secretive history of her grandfather’s work with the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The book required vulnerability and conversations that were long overdue. Strasser sifts through her family’s memories and travels the world in order to rebuild the story that no one wanted to tell. Now, the book has won the 2024 Reed Prize in Environmental Writing from the Southern Environmental Law Center and is a finalist for the Minnesota Book Award.

Emily is an alum of the University MFA program where she spent time researching and writing Half-Life. Her work has also appeared in Catapult, Ploughshares, Guernica, Colorado Review, The Bitter Southerner, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, and more. She received an AWP Intro Award and was a McKnight fellow among many other accomplishments.

Impressed by her work and recent award, I invited Emily for a Spotlight Series interview:

Hannah Karau: Emily, it’s nice to have you here. Thank you very much again. So your book Half-Life of a Secret: Reckoning with a Hidden History just won the Reed Environmental Writing Award and is a Minnesota Book Award finalist! Huge congratulations for that. The book is quickly gathering prestige. Can you tell me about the writing process and how it felt to divulge into those secret histories?

Emily Strasser: Yeah, thank you. This book took me about 10 years to write. It was very intensive and took a lot of research. So the book traces my journey to reckon with the legacy of my grandfather's work building nuclear weapons in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which is a secret city built by the Manhattan Project to build the first atomic bomb.

It involved me learning about a lot of things that I knew nothing about. I did not study science at all, so I had to learn about nuclear weaponry, World War Two history, physics, all kinds of things. I traveled widely: I went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I went to the Nevada test site outside of Las Vegas, where they would test the nuclear weapons. I also spent a lot of time in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where my grandfather had lived and worked, and did a lot of archival research. So it's both deeply personal and has a much wider scope than that. I did a bulk of that work over my time in the MFA.

Then you asked about what it was like to divulge these hidden histories. So for a little bit of context, this was not a story that my family spoke much about. And in many ways, this history is still sort of suppressed nationally. Oak Ridge was built as a secret project and was a secret during World War Two. Of course, after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it was no longer hidden, but there's still a culture of secrecy around it and a lack of national reckoning about it. I was also divulging and exploring some more personal, family secrets around mental illness. So yeah, it was quite vulnerable to publish a book that was both so personal and so political. And I think I was able to write it because I tricked myself into thinking no one would ever read it. I mean, I did have readers along the way. I had my MFA colleagues, I had friends and family who read it, editors, people like that. But it wasn't until I had a publisher secured that I was gripped by the pure terror of what would happen when real people who have real connections to this history read this book. I felt quite vulnerable, but the response has been quite lovely.

I’ve gotten to hear from a lot of people who have personal connections to this history or who have their own family secrets that they are interested in that they have shaped the textures of their lives. People resonate with the book in a variety of ways. So my worst fears about its publication have not yet come to pass.

HK: I'm glad that the response was better than you were expecting. I think it’s normal to have fears about publishing personal things. So it's really good when that goes better than planned. I'm curious, you said it took 10 years. Wow! How much time during your MFA did you have to go traveling, researching, and meeting people?

ES: Well, a great thing about the MFA program at the U—I don't know about all of them—is that there are opportunities for research funding. There are lots of pots of money both within the program itself and within the university at large. So I applied to a lot of different grants and I was able to go both to the Nevada Test Site and to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They both happened while I was in the MFA program over the summer. I applied to some grants that were external to the university as well, but there are opportunities within the program.

HK: Awesome. All right. So you have a lot of other great accomplishments to your name as well. The McKnight and Olivia B O'Connor fellowships, writing in Best American Essays, the AWP Intro Award and plenty more. How have these successes impacted your life and writing since?

ES: Yeah, of course, winning awards is lovely validation, especially when you're working on something very hard for a very long time. And it's solo work often, so it's always nice to be recognized. But it can be a bit of a double edged sword, like you never want to be writing for the sake of getting recognition because you're always going to have moments when you don't win the thing. For everything that I've won, I've not won ten other things that I applied for.

I think it's important for people to know that it is a game of numbers. It's a game of a lot of things. Looking at a list of people's successes, you can think “Oh, it's easy.” I just don't want people to be discouraged if they haven't yet gained external recognition. There is the element that it resonated with people, and it resonated with people who have the power to confer some honor. It’s wonderful when that happens, but also it's so random. Like who are the people who have that power?

It's important not to let awards and recognition be the driving force. You know, for one example, I won the Ploughshares emerging writers award with an essay in 2015, and then later it was an honorable mention for Best American essays. I had submitted that essay to that same contest, or different contests, like three or four years in a row. I revised it between submitting each time because I knew that it could get better, and it got better, and eventually it won. And then agents started contacting me based on that essay, but it took persistence.

HK: That’s so encouraging!

ES: If you believe in it, you know, keep at it.

HK: That's really great, Emily. So to take a turn here, as an alum of the University of Minnesota MFA program, can you share what parts of the program have been most beneficial to your writing career so far?

ES: Sure. I think the biggest thing was time and space to write. Not all MFA programs are funded, so some of them you have to pay for. The University of Minnesota MFA is funded, which means that you teach undergraduate classes or some people get a fellowship instead. So I did teach the whole time in exchange for tuition and a small stipend. It’s not a lot of money, but people manage to make it work, or they do side hustles and make it work. That is a huge gift to have.

It’s three years—a lot of MFA programs are only two years—where your main job is reading and writing. I’d say that's the biggest benefit. But certainly, the mentorship I gained there was huge and also developing a great writing community. I'm still friends with a lot of the people in my MFA program, and they're still people who will read my work, you know, and who I exchange work with now. Those are the biggest things, then we already mentioned research funding, but that was super helpful, too.

HK: Awesome. That's really good to hear, too—that that community outlasts the MFA program. It’s great that you really get to keep up with those people and keep having those writer friends.

ES: Yeah! The cohorts are small, and a lot of people move for the program, so when you come and you don't know anyone in the city you have built-in friends.

HK: So You form friendships quickly. You can't help but get close to them. So now that you've been done with school for a bit, and you're doing quite well in your field, what advice would you give to writers who are beginning their career and who may be interested in an MFA?

ES: Yeah, I think MFAs are great, especially if they're funded. I wouldn't advise anyone to go into debt to get an MFA. It's not a degree that has any guarantee of financial payoff. In fact, it has more of a guarantee of financial insecurity if you decide to pursue the career of being a writer. So take that for what it's worth.

I took a few years between undergrad and grad school, and I'm really glad I did. It helped. I was interested in an MFA when I graduated, but I decided not to apply right away. And I think it helped to make me more focused and dedicated when I got there. It also gave me a little bit more life experience. It can be hard if you've been in school so long, to just go straight to more school. And if the reason you're going is because you're not sure what to do next. You're gonna bring a different level of motivation and dedication, than if you're sure that you want to be writing in a serious way. Some of my colleagues did come straight from school, and they're amazing writers, and they were very dedicated, so I'm not trying to say anything negative about their paths. But for me, it was really good that I took the time in between and it kept me motivated and focused.

HK: Yeah, I think you're right that with it being a degree that doesn't necessarily guarantee financial stability, that it is a good idea to be 100% Sure.

ES: And that said, people do different things after the MFA. Because nobody has full time writing without another job. Unless you're–

HK: Stephen King or something?

ES: Stephen King, exactly. But some of them are high school teachers, or managing nonprofits or teaching college courses, like there's a lot of different things, and people manage to keep up a writing life in a lot of different ways.

HK: Yeah, there's still plenty you can do. So back to you, Half-Life has been out for almost a year. Can you tell me about your next writing project, or the next big thing that you're working on or thinking about?

ES: So it's still early stages, I'll say that. Half-Life took me so long that I was really tired when I finished. They also don't tell you that when a book comes out, the writer has a lot of work to do as far as publicity, which is not something that I like to do, or that I'm good at. So it takes a lot out of me. Although things like doing events have become easier than it was at the very beginning. So I'm grateful for that.

Anyway, I'm only in the early stages. But I'm working on essays broadly linked by climate grief. And I won't go deep into it, because it's very much a baby. But I will say that I'm excited to work on it. I'm not envisioning this as like a single narrative, the way that Half-Life was. I think I need to shift my pace a little bit to working on essays that can be kind of published one off or finished more quickly than a whole book.

HK: No, that makes sense. And I think that's a good and interesting topic. I know it's a baby project, but can you tell me a little bit more about grief over climate change?

ES: Yeah, so it spurred from my own experience a few years ago of reading something that really touched my heart and kind of blew me wide open. My thinking went to sort of a transcendent place of a lot of gratitude for my life and the beauty of the world, and also a place of deep despair about, what if it's too late, you know? And that sent me on a journey of reading and seeking out spiritual frameworks for thinking about climate grief. So it will be sort of circling around those experiences and picking up different threads related to that.

HK: Very cool. Thank you for that. I think that's all the questions I have for you, but I really appreciate your time and thoughtful answers! And the insight on your upcoming work, of course. Good luck with the final round of the MN Book Awards as well!