Remembering Catherine Ella Blanshard Asher

Catherine B. Asher, professor emerita of art history at the University of Minnesota, passed away in her Minneapolis home on April 14, 2023. An expert on premodern South Asian and Islamic art and architecture, Professor Asher—or Cathy, as she was lovingly called by everyone from undergraduates to senior colleagues—published important scholarship and taught and trained hundreds of undergraduate and graduate students. Her research engaged a wide range of topics in South Asian art and Islamic art around the world, covering the 7th century to the present.

Leading by Expertise

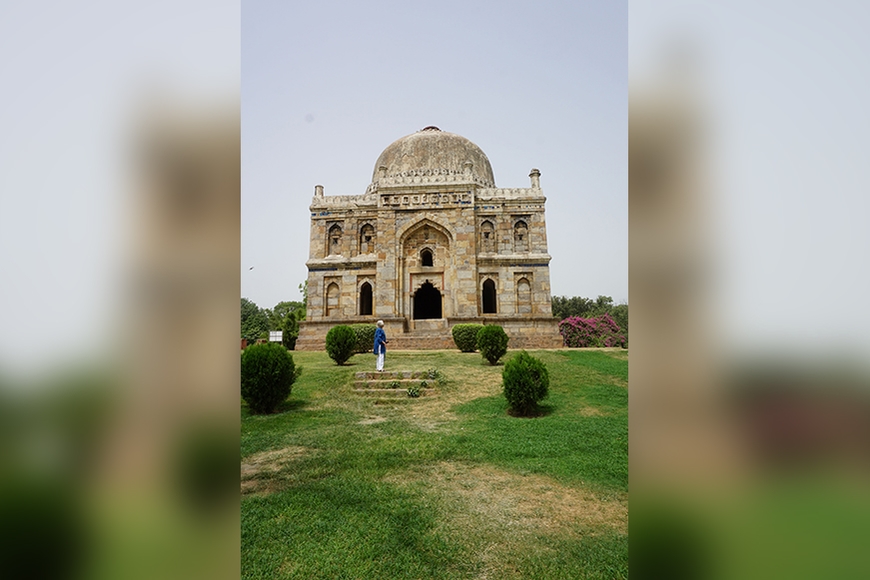

Her global approach toward Islam, its past, and its cultural heritage was exceptional and truly visionary both within the discipline of art history and within Islamic studies more broadly. At a time when Islamic art and history focused overwhelmingly on the Middle East, Cathy’s dissertation, “The Patronage of Sher Shah Sur: A Study of Form and Meaning in 16th Century Indo-Islamic Architecture,” brought to light the architectural patronage of Sher Shah Suri in its Indian contexts. Sher Shah was a powerful warlord who took control of northern India, after defeating in 1540 the Mughal emperor Humayun, who was then forced to live in exile at the Safavid court in Iran. Cathy’s groundbreaking study identified the significant contributions to architecture and public works by a figure remembered only peripherally to the famed Mughals.

In a similar vein, Cathy’s first book, the Architecture of Mughal India, as part of the New Cambridge Series on the History of India, braided together well-known monuments and personalities of early modern northern India with those previously little-studied. Still the major reference book on the subject, it was commissioned when she was a graduate student, concurrently testifying to the thoroughness of her research and the charming clarity of her writing. It was revised and republished in 2001.

Cathy’s latest book, Qutb Complex: The Minar, Mosque and Mehrauli was published in 2017 by Marg Publications. In addition, together with Thomas Metcalf, she co-edited Perceptions of South Asia’s Visual Past in 1994, and with Cynthia Talbot she co-authored India before Europe, a kaleidoscope of India’s cultural history from 1200 to 1750, published by Cambridge University Press in 2006 with several subsequent reprints, and a new revised edition in 2022.

Having authored many important entries in the foremost reference works in both art history and Islamic studies, such as the Oxford Bibliographies in the History of Art, the Encyclopedia of Islam and the Encyclopedia Iranica, Cathy also wrote significant research articles that have had a lasting impact within South Asian and Islamic art histories. For example, “A Ray from the Sun: Mughal Ideology and the Visual Construction of the Divine,” (in The Presence of Light: Divine Radiance and Religious Experience, ed. Matthew Kapstein, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004) appears on most syllabi on Mughal history and has now become required reading for many historians of premodern Islamic art in India and elsewhere.

Cathy’s list of publications is long and impossible to mention here in full. An overview of the titles of her articles, lectures, and other academic contributions nevertheless gives a glimpse of the expansiveness of her interests and her defiance of superficial categorizations. These testify, as a result, to her bold but airtight arguments that strived to push standard temporal, geographic, political, and cultural boundaries within Indian and Islamic art histories. Cathy’s scholarship rejected narrow understandings of religious identity and artistic production. Her books and articles ranged freely from Sufi shrines to Hindu temples. Her scholarship on the Taj Mahal and its afterlives engaged directly with the politics of religion, identity, and nation.

As evidence of her diligence, Cathy worked on her last article until her last day of life. That final article, “New Policies, Changed Attitudes: Temple Construction under the Mughals,” will be published posthumously in the foremost journal in the field of Islamic art and architecture, Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Cultures of the Islamic World, in the fall of this year.

An Adventurous Approach

A model scholar and a world-renowned expert on Mughal architecture, who shared her work freely with academic and lay audiences around the globe, Cathy was an inspiration to her faculty colleagues. Her pragmatism and integrity in departmental leadership and governance were invaluable, and she was a trusted mentor to her junior colleagues, especially the women for whom she served as a beacon. Jane Blocker remarks that “it was easy to love Cathy for her genuine kindness, limitless generosity, devotion to the department, and unpretentious brilliance. She was such a lovely human being that you forgot to be intimidated by the enormity of her CV.”

It was these qualities of character as much as expertise that made Cathy’s classes captivating. Former student Sinem Casale, now associate professor of Islamic art at UMN, recounts: “I remember always trying to find a seat in one of the front rows, to be able to see more clearly the incredible number of images she would show in each class, to not miss anything in my notes.”

In addition to the obvious depth and breadth of her knowledge, she was also a gifted storyteller. The scholar of Ottoman architectural history, Nina (Cichocki) Macaraig recollects how Cathy taught a collection of animal fables originating in India that became widely popular in the Near and Middle East, the adventures of the two clever jackals Kalila and Dimna. In a memory book her former students prepared for Cathy a few months before her death, Nina wrote: “I am still laughing about the way you narrated Kalila wa Dimna!” Indeed,Cathy’s classroom lectures were often interrupted by bursts of laughter, but they did not just provide entertainment. By drawing students into the narrative, she had an ingenious plan to teach them a fundamental tool of art historical study: the skill of close looking, sustained by an eagerness to learn every bit of an artwork’s charms.

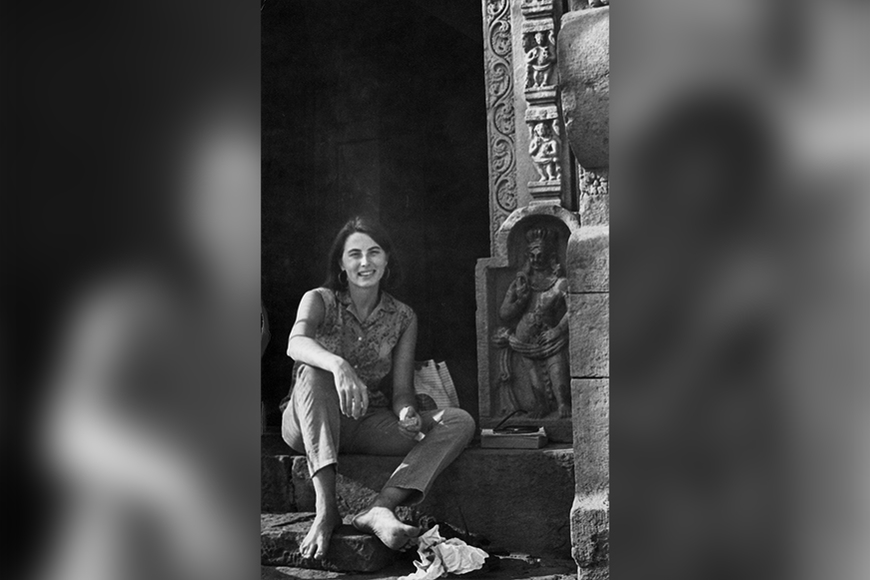

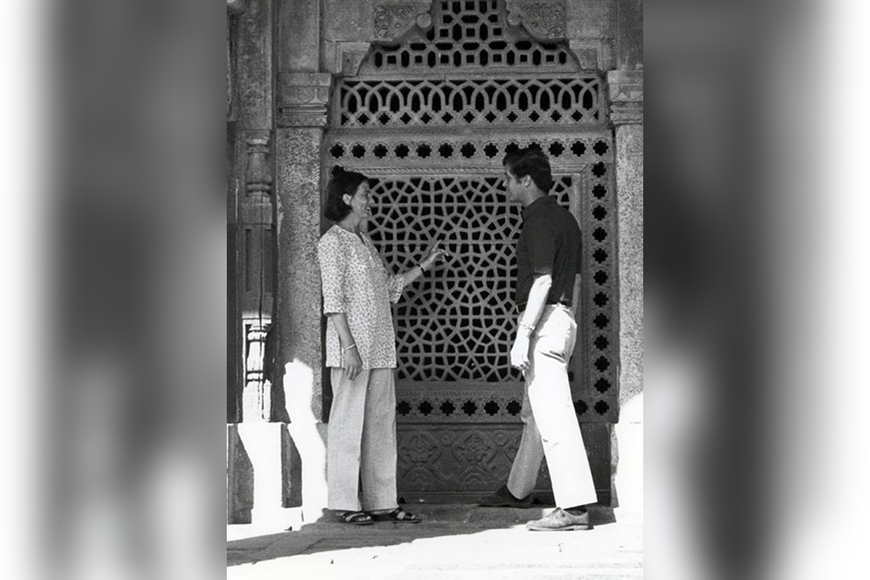

In Cathy’s classes, objects and especially buildings were both enlivened and made memorable because she so often added something personal about her visits to them. Acutely aware that many students in her classes had not traveled to the mosques, temples, palaces, and other monuments she showed (and perhaps never would), Cathy described her own adventures. Those personal narratives about going to and being in those spaces gave students so much more than what is typically included in textbooks and specialized studies. It also became apparent that many of the photographs she showed in classes were taken by her, at times under very difficult circumstances. These involved crossing deserts in taxis and traveling to remote villages on unpaved roads. After discussing a particular temple, she said that Rick (the late Prof. Frederick Asher, her husband and renowned UMN professor of Indian art) had told her that they might be able to reach it, but that he highly doubted if they would be able to make the trip back safe and sound. With typical sardonic brevity, Cathy concluded that “it was a somewhat hard journey.” Her perseverance allowed students to see and study sites oceans away in Minnesota. Persistence in the face of difficulty was, to many, one of Cathy’s most defining traits--in life as in scholarship.

Field trips became part of the Ashers’ way of living and travel frequently included their children. Major scholars in the field have shared fond memories of meeting with all of them in India. The eminent Austrian scholar of early modern India, Ebba Koch recollects: “Cathy, her husband Rick, and their children Tom and Alice visited India repeatedly for longer research stays in association with the American Institute of Indian Studies. Our common interest in Sultanate and Mughal architecture brought Cathy and me together and we often met in our house in Amrita Sher Gill Marg in New Delhi for lively discussions and interchanges. We also visited monuments together, memorable was an excursion to Varanasi, then still Benares, and Rohtasgarh in November 1981.”

Likewise, the prominent Bangladeshi scholar of Indian architecture, Parween Hasan also highlights Cathy’s friendship and collegiality: “It was probably 1978 when Cathy and Rick visited Dhaka with their children and were frequent visitors in our home. I went on my first field trip with them to North Bengal and learnt from them how to measure a mosque. I had always held their scholarship in very high esteem but was amazed at the generosity with which they shared their knowledge and expertise with others.” Over the years, in those countless research trips, Cathy and Rick amassed a large and important collection of photographs and ground plans. They now constitute the Frederick and Catherine Asher Archive at the American Institute of Indian Studies in Gurgaon in India.

Round-the-Clock Advising

Cathy and Rick cared genuinely for each one of their graduate advisees, whom they tended to mentor together. Many realized only much later what a privilege it was to have found in Cathy much more than a model scholar. Venugopal Maddipati (UMN PhD, 2011), now an assistant professor at Ambedkar University Delhi, remembers how she read his papers, draft after draft, insisting that he learn to write clearly: “And that's the thing about Cathy. She was incredibly perseverant. She would call a spade a spade. And she would simply never give up. Helping me improve as a writer must have been an arduous task, if for no other reason than the fact that I stubbornly clung on to dangling clauses for nearly six years as a graduate student!”

As an undergraduate, John Jochman took only one class with Cathy, but the Minnesota anaesthesiologist still remembers how precise and witty she was: “I first met Prof. Asher in 2004 in a course on Islamic art. She was incredibly warm, approachable, and highly knowledgeable on the material. The class was fantastic. I remember writing a very long paper and trying to keep it within the recommended page limit by widening the margins and narrowing the lines. She graded and returned it to me with a note to keep the spaces standard because ‘I don't care how long it is!’ I just found that so funny, and it has stuck with me since.”

Graduate students likewise remember the legendary dress rehearsals they had to perform before formal presentations at conferences. While these so-called “dry runs” were standard procedure for all PhD students, in the case of Cathy’s students there were often dry runs in preparation for the dry run! These took place wherever it made sense: in her office, on the phone, or at her house. By the time of the actual conference, which she often attended, Cathy had already spent hours listening to each of her students’ talks. No one graduated with a PhD supervised by Cathy Asher without perfecting the art of argument-driven and perfectly timed presentations.

Prolific in her scholarship, Cathy had little patience for pretentiousness and worked hard to make everyone feel welcome. Natalia Vargas Márquez (UMN PhD, 2020) recounts: “My fondest memories of Cathy are in meetings, talks, and workshops. Sitting next to Cathy was always a treat, telling it like it is, and making us, grad students, in many cases from communities that were marginalized by academia (women of color, international students, queer students) feel seen and welcomed.”

And, in the spirit of her lively lectures, she did not tolerate dullness even in the delivery of a most brilliant argument. Former student Riyaz Latif (UMN PhD, 2011), now an associate professor at Flame University in Maharashtra, India, recalls being seated next to Cathy at an art history seminar at another institution: “when she slips me a hastily scribbled note at the peak of the speaker’s scholarly exposition: ‘This guy is boring the life out of me!’ I had to make a rigorous effort not to chuckle and draw attention to myself.” Jennifer Marshall, Professor and Chair of the UMN Art History Department, confirms that “sitting next to Cathy always tested your skills of decorum. Her asides were always so deadpan and delicious!”

In the months since her death, Cathy’s students have offered their memories of sharing both laughter and tears with her, reflecting especially on the privilege of spending incalculable hours at their advisor’s office. Not everyone gets lucky enough to have an academic mentor who always makes time to listen, whether the issue at hand, in the case of Cathy’s advisees, was about getting a driver’s license, renting a house, buying a winter coat, obtaining a visa, or structuring material for their dissertations.

Many of Cathy’s students came to the University of Minnesota from India and elsewhere, just to study with her. Despite the distance and, for some, the exoticism of Minnesota, all students found a genuine home away from home in Cathy and Rick’s generosity and hospitality—especially at their unforgettable dinner parties. Former student Deborah Hutton cites Cathy’s sense of humor, devotion to family, scholarly intellect, and dogged work ethic, as some of the fundamentals that she embodied and instilled in everyone she mentored. Cathy’s former students—who in time became colleagues and friends—are today spread out all over the world. Many of them now hold professorships and are training new generations of students in Islamic and South Asian art histories. May her warmth, her wit, and her no-nonsense brilliance continue to guide both the pedagogy and study of the places and people she loved so much.

By Sinem Casale, UMN Associate Professor of Art History,

and Anna Seastrand, UMN Assistant Professor of Art History