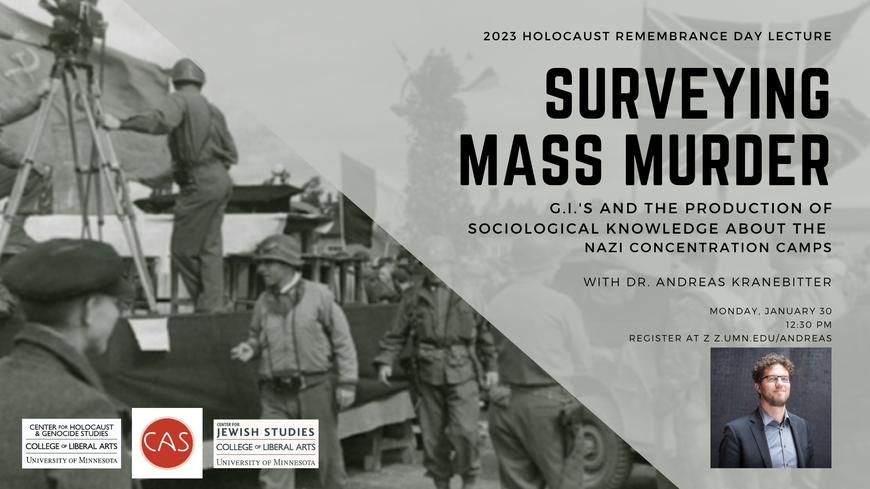

Surveying Mass Murder

Soldiers of the U.S. Army (GIs) were among the first to scientifically deal with concentration camps upon their liberation when writing intelligence reports for the Psychological Warfare Division (PWD) of the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) or the Office for Strategic Services (OSS). The PWD and OSS teams consisted mostly—but not always—of GIs who had been trained at the Military Intelligence Training Camps “Camp Ritchie” and “Camp Sharpe” in Maryland and Pennsylvania. Many of these soldiers, known as Ritchie and Sharpe Boys, had been forced into exile from Germany and Austria as Jews and political opponents.

From 1942 on, they were trained in intelligence, interrogation techniques, close combat, photo interpretation, etc., a knowledge they used for the interrogation of POWs and the production of leaflets and radio broadcasts intended to destroy the morale of the Wehrmacht. When these teams eventually arrived at the recently liberated concentration camps in April 1945, they were often tasked with investigating the camps' history. Along with the memoirs of the camps’ survivors, these reports represent the first kind of “scientification” of the concentration camps. From the perspective of a sociology of knowledge, this research could be called a “third culture” of knowledge production—a knowledge production beyond the more individual literary or juristic evaluations, a social scientific, methodologically thoughtful investigation into a collective experience aiming at theoretically understanding the concentration camps.

In this talk, I want to focus on this early research on the camps before, while or immediately after liberation, i.e., before they were history. What was this type of “third culture” research on concentration camps? What methods and concepts did they use in their research? What were their findings, and how relevant are these reports for today’s research on concentration camps? Writing the history of their practice means writing the history of scientific and military resistance against the Nazi regime.

Andreas Kranebitter, political scientist and sociologist, currently serves as the acting head of the Archive for the History of Sociology in Austria at the University of Graz and has most recently been appointed the new director of the Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance (DÖW) in Vienna. Recent publications include “Authoritarianism, Ambivalence, Ambiguity. The Life and Work of Else Frenkel-Brunswik” (editor of a Special Issue of “Serendipities. Journal for the Sociology and History of the Social Sciences”) and “Die Konstruktion von Kriminellen. Die Inhaftierung von “Berufsverbrechern” im KZ Mauthausen” (Vienna: new academic press; in preparation).

Organized by the Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies and the Center for Austrian Studies. Presented with the Center for Jewish Studies.