On Purpose: Portrait of Classical & Near Eastern Studies

בְּרֵאשִׁית

In the beginning...

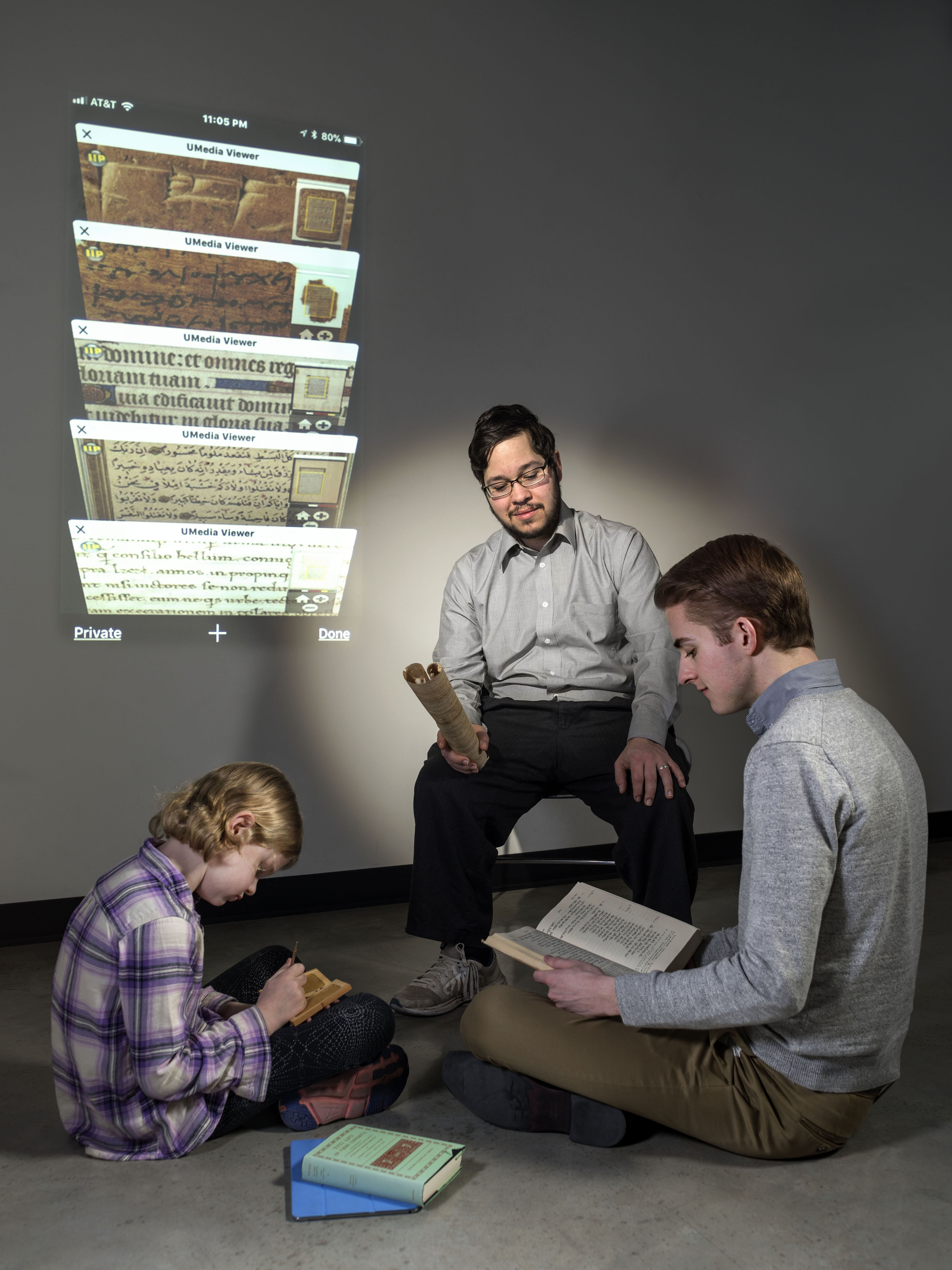

Humanity likes to keep records. We have written notes to ourselves for thousands of years, preserving everything from tax receipts and official speeches to narratives of war and songs of praise. Any medium could be pressed into service: clay tablets (Mesopotamia); papyrus rolls, broken potsherds, or wax tablets (Egypt, Greece, and Rome); parchment codices and printed books (late antique, medieval, and early modern eras). Most recently, we have reverted to scroll and tablet with digital media.

The Department of Classical and Near Eastern Studies explores the peoples of the ancient Near East and Mediterranean. Their writings survive in some cases on the clay or paper or stone used by the original scribe, and in other cases through a long chain of copies. We study works that have survived largely complete, like the Iliad and the Aeneid, and works that are now fragmentary, like the epic of Gilgamesh. We study sacred texts (including the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and the Qur’an) and secular texts, like love poetry, comedy, and satire. Our students might learn about politics in Cicero’s Rome, or law and (dis)order in the ancient Near East, or gender roles in the Bible.

The ancient world can seem both remote and disconcertingly akin to our own. Letters from third century BCE schoolboys asking their parents for money could be translated and sent as an iMessage from a Middlebrook dorm room to Eau Claire today without changing a word. Contemporary theater, like the recent Rarig Center production of Welcome to Thebes, can draw on Greek tragedy to examine modern warfare. The political upheavals of the past year in Britain and the US have produced an explosion of blog posts and op-eds invoking the Greek historian Thucydides or famous (and infamous) Roman emperors. Students in our courses on death and the afterlife or gender and sexuality are often shocked more by the similarities to our own practices than the differences. But, as the Roman comic playwright Terence said, we have a common bond: homo sum, humani nil a me alienum puto, meaning “I’m human: I don’t think anything human is foreign to me.”