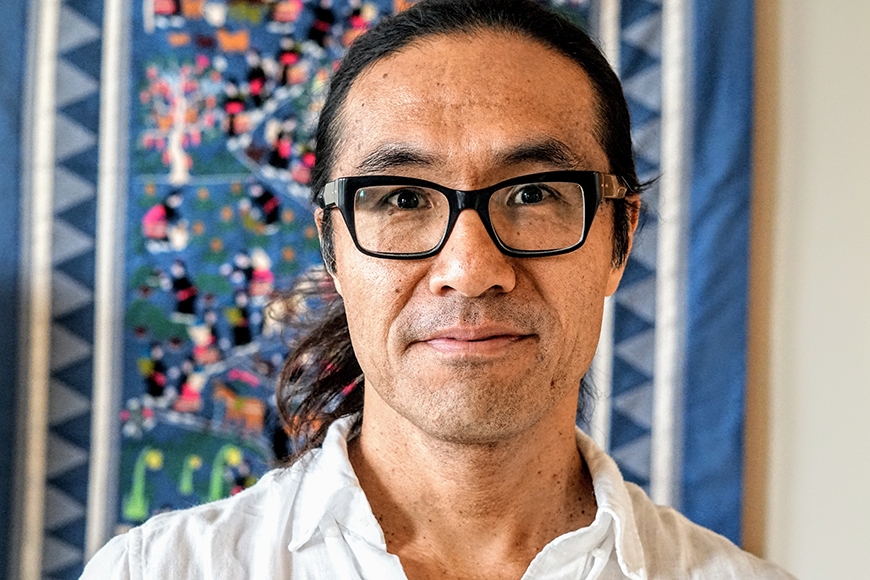

Q&A with Yuichiro Onishi

Yuichiro Onishi is an associate professor in the Department of African American & African Studies (AA&AS) and the Program in Asian American Studies. He’s an African Americanist trained as a historian of modern America. In this interview, Onishi discusses the importance of his research, teaching, and the AA&AS department.

What do you think other people should know about your research?

My work specifically centers on the study of Black thought and struggles in relation to Japan and Okinawa. I am continuing the work I started in my first book, Transpacific Antiracism (NYU Press, 2013). It rests on the question of liberation, on the one hand, and “the problem of the color line,” as W. E. B. Du Bois pronounced at the turn of the twentieth century amid a triumphant rise and expansion of colonial modernity, on the other hand. I explore the relationship between the two: the question of how to be free and learn to live together in a highly unequal and uneven world where race—a marker of difference and a mechanism of differentiation—dynamically imbricates relations of domination and emancipatory strivings.

This dialectical inquiry takes a specific passage for me. I make an inroad into the domain of modern political and cultural formation that I call transpacific phylon, which is conceptualized as a point of contact and entanglement between the Afrodiasporic world of critical thought and Japan and Okinawa. Phylon is the Greek word for race. I consider transpacific phylon as a modality through which the question of liberation can be taken up, both politically and ethically, to fashion a distinct Black philosophical discourse that can help discern how to reconstruct democracy in a world built by race.

Can you describe one of your current or recent research projects?

The current project is a collection of essays. It introduces, in an idiosyncratic way, manifold Afro-Asian linkages to explore such topics as Du Bois’s conception of the moral law, a political theory of mutual aid, Marxism in the United States, Du Bois’s sociology, Black feminist theory and practice, and aesthetics. The importance of a book of this kind is that the discussion of Black, Japanese, and Okinawan thinkers and artists’ engagement with transpacific phylon is not strictly philosophical. Rather, it engenders a metanarrative of liberation that can inform those entering into the world of organizing on matters of solidarity. It issues a challenge to work through ethical demands of liberation, which involves learning how to become together in opposition to systems of domination by reaching across differences in experiences and histories. Afro-Asian solidarity, for this, is not an end. Instead, it is better understood as a means to an end; there are many itineraries and detours, too.

My work considers what it takes to think through differences to resolve what Du Bois once called “the problems of human living-together.” I recently co-authored some of my preliminary thoughts with colleagues in Japan: Du Bois’s connection with Toyohiko Kagawa in the 1930s, the father of the modern cooperative movement, and the artistry of Paule Marshall and Abbey Lincoln, especially their labor of creating literature and music in relation to Japan as a point of entry into Afrodiasporic feminist thought.

What are some ways that your research influences your teaching and vice versa?

Students who come to the Department of African American & African Studies and Asian American Studies Program do so with deep desires on their part to explore the fundamental problems of the modern world that are tethered to the legacies of colonialism and chattel slavery, as well as ongoing militarism and empire-building. Far from unloading the dead weight of discontent, our intellectual work encourages students to dig deep so that they can begin to construct critical agency. It guides students in sowing the seeds of passion for justice, as well as openness and readiness to actually construct new futures in the present.

My goal in both teaching and research is to carve out such a space of inquiry for “futuring,” the notion coined by environmental justice activist-scholar Bunyan Bryant. It has helped me get at the imperative of fashioning critical agency, and I learned this particular category of struggle from reading Grace Lee Boggs’s Living for Change. In the back of my mind sits, for instance, critical thoughts of James Baldwin and Martin Luther King, Jr., especially their perspectives on militarism that they articulated during the Vietnam War era; writings of W. E. B. Du Bois, C. L. R. James, and Charles W. Mills, as well as the poetry of Aimé Césaire and Jayne Cortez that upend Eurocentrism and other types of normativity; Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama’s life in the struggle; and the aesthetic, cultural, and political authority of A Grain of Sand, the Asian American Political Alliance, Asian Americans for Action (co-founders, Kazu Iijima and Minn Matsuda), and Blue Scholars’ “50 Thousand Deep.”

I believe in Césaire’s provocation: “Poetic knowledge is born in the great silence of scientific knowledge.” It is at the core of what I do as a scholar and a teacher.

What is something not many people know about AA&AS?

AA&AS represents a cross-section of the totality of the humanities, social sciences, and the arts; our faculty contribute to African studies, African American studies, Caribbean studies, and African diaspora studies. Our work is not at all about identity politics, although this perception is widespread. It is entirely of the mainstream; I actually think of it as a subterfuge to devalue what we do. The irony, of course, is that whiteness derives its authority from identity politics, which is tied up with, historically and to this day, private property interests buoyed by individualism—that is, access to power, privilege, knowledge, and wealth. We fundamentally critique this problem.

We have scholars trained in history, comparative literature, sociology, political science, economics, music, critical ethnic studies, archaeology, ethnohistory, and cultural studies. But our interventions are always quite specific. We center African and African-descended peoples’ lives, livelihoods, pasts, sociality, struggles, politics, artistry, poetics, critical imagination, and worldliness to transform the whole knowledge structure created and perpetuated through domination. What we do becomes flashpoints and sites of transformative education.

AA&AS is also home to incredible linguistic heterogeneity. We offer two African languages: Somali and Swahili. These are less commonly taught languages that are connected to diasporic communities in Minnesota. In addition, our faculty and staff speak Somali, Arabic, Swahili, Yoruba, Wolof, Oromo, Tigrinya, French, German, Portuguese, and Japanese. Many of our students come from multilingual milieus as well. This specificity makes AA&AS singular within the College of Liberal Arts, and I do think dynamic cosmopolitanism resides here.

This interview was conducted by an undergraduate student in Backpack. Meet the team.