Meet the World’s First Dakota Language Majors

The University of Minnesota’s new Dakota language major connects both heritage and non-heritage students with the Dakota language and traditions.

Introduced in fall 2023, the major is part of the movement throughout Dakota communities to increase the number of Dakota language speakers and teachers. It immerses students in the Dakota language and culture to gain a high proficiency in the language. With only about five first-language speakers born and raised in Minnesota and about 20 first-language speakers outside the state, there are more second-language learners than first-language speakers. The program prepares students to have a sophisticated understanding of the Dakota language while giving them the skills to fulfill the growing need for immersion teachers.

Vicente Diaz, chair of the American Indian studies department, explains why this program is critical. “Launching this degree program and continuing to fight to ensure that it receives the resources—like faculty and staff that know Dakota realities—that it needs to thrive are absolutely essential for advancing Dakota peoplehood, because that's the right thing to do, and for advancing the field of Native studies, because Dakota language and culture furnish us rich and inspiring material for intellectual and academic excellence,” he says. “It is also important to ensure the success of the Dakota degree program because it provides the material to transform the University of Minnesota and Minnesota society from the settler colonial values and perspectives that founded them if we are truly committed to true social justice and decolonization.”

At the end of their first year, three of the first students—in the world—to major in the Dakota language reflect on what the program means for their personal language journeys and for the future.

A Language Linked with Culture

The land Mni Sóta Maḳoce is home to the Dakota people, with many names of locations in the State of Minnesota coming from Dakota words and traditions. From cities like Mankato, Shakopee, and Wayzata to natural landmarks like Minnehaha Falls, these words are rich in meaning and express volumes about the land and histories of the Dakota people.

“It's the language that connects with those places. There's so much history behind it because you have families who have gotten married there. You have these stories that come along with these names, and these names for places,” says Summer Jensvold, a Dakota language major. “The word Minnesota describes lands that were like cloudy water, but it goes way beyond that. It talks specifically about when the water is very glassy and there's no waves and you can see sky mirroring directly with the water. The language goes so much deeper and explains more about the world and how Dakota people had always interacted with it prior to colonization.”

The U is part of that colonial legacy. It was built on stolen Dakota land, displacing people who had lived and cared for the land for thousands of years. Investment in American Indian studies and the Dakota language program is “a step in the right direction” toward acknowledging the U’s history.

“[The major] opens that door for more people to learn, which in general will help language revitalization and help the language to survive and thrive at the same time,” Jensvold adds.

Jensvold, whose Dakota name is Eagle Road Woman, is from the Pejuhutazizi (Upper Sioux) community. Her grandmother was an immersion teacher in 1997 in Minnesota’s first and only Dakota immersion school, so Jensvold grew up learning the Dakota language from her. Her first words were in Dakota, and she spoke it as a child. Even at an early age, Jensvold understood the importance of knowing and learning the language.

“It's hard to be Dakota without the language. They're synonymous with one another. When you separate the two, you lose a lot of nuance and culture behind the language,” she explains.

She continued studying in high school under the teaching of Carrolynn (Kunsi Carrie) Schomer, a first-language Dakota speaker and former UMN professor in the Dakota language program. Jensvold wanted to pursue studying the language post-secondary education, and learned about the Dakota language major while looking into the Native American Promise Tuition Program.

“I'm one of the last few generations that's going to have that direct connection to a first language speaker,” she says. “I need to do this for my own children, for my own grandchildren, and for my community.”

Jensvold has been learning the Dakota language for 18 years and is in a class for intermediate to advanced speakers. She attends classes from 6:30 AM to 4:30 PM every day, but even in her free time, Dakota words fill her mind, sometimes coming to her unexpectedly. “That's kind of how the language is and how it works into the Indigenous way of being. It's like the language is a living breathing thing. And so that carries on in your every single day,” she says.

Jensvold also enjoys learning in an immersive environment, especially when she gets hands-on lessons about making things. She discovers new words all the time while crafting and learning how to describe the process.

“You're always learning something new and I really, really love that,” she says. “It's a little tough at times, but it's the beginning of a journey for me, and I look forward to it.”

A Grounded Worldview

Evelyn Ashford, pursuing a double major in American Indian studies and Dakota language, reflects on the importance of learning the language as someone outside of the Dakota community. Ashford is white with Indigenous Sámi heritage, and is also on a personal journey to reclaim her own heritage. She learned about the Dakota language major from her language instructors C̣aƞte Máza and Ṡiṡókaduta while originally taking coursework for the Daḳota Language Teaching Certificate. By studying the language, she hopes she can understand more about what the Dakota people have gone through, both in the past and presently. “I’m here supporting the language and supporting the Dakota people,” she says.

Ashford hopes that with time, the Dakota language major can bring the Dakota language back into common use for heritage and non-heritage speakers, and hopes to help. Knowing the language also gives one a better understanding of Dakota ways of thinking, which she believes can be beneficial to all.

“Dakota thought carries sustainable, environmentally sound practices, and conveys being in good relationship by caring for all of our neighbors and relatives,” she explains. "Our world is in desperate need of such grounded, caring thought and worldview.”

Building a Future for Dakota Speakers

Wakiƞyaƞ Waƞbli also envisions a future where Dakhódiapi or Dakhód is spoken more widely, which begins with creating more accessible spaces for the language to be spoken and learned.

An enrolled member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, he has been recognized as a dedicated student of Dakota from an early age. “My grandparents supported my language journey as a child by providing connection, care, and culture on the Sicangu Oyanke or the Rosebud Reservation,” he says. He was awarded an internship from the Leech Lake Tribal College to study Dakota and would commute four hours to attend lessons immersed in Dakota with language specialists like C̣aƞte Máza. He graduated from the Leech Lake Tribal College with an associate’s degree in Indigenous leadership. He knew the University of Minnesota offered a Dakota language certificate, but he wanted to pursue it as a major.

“I was persistent in asking my teachers when the Dakota language program was going to have a degree,” Wakiƞyaƞ Waƞbli recalls. “For every class period, I would stay after class to speak with my instructors in Dakhódiapi. That's how I formed that relationship and then started to learn about how much work they were doing behind the scenes in order to make that a reality.”

Wakiƞyaƞ Waƞbli spreads awareness that Dakhódiapi was systemically oppressed, disrupted by colonialism, and stolen from the Dakota Relatives. “It’s great to recognize all of the relationships that have protected our ways of being with Dakhódiapi and the systems of reciprocity that generations have developed with the future being at the forefront,” he says. He wants to remove barriers and create more safe communal spaces for Dakota to be spoken in public spaces. That is why he chose to focus on content creation through social media platforms and is committed to honor his home community, Hiƞhaƞ Suƞ Wapaha Oṫunwe.

“I appreciate everyone who has held space and shared their time,” he says. “I have been able to communicate and facilitate with the other dialects of Dakhódia. We have all held space and shared conversations in Dakhódiapi.”

Wakiƞyaƞ Waƞbli facilitates a safe language space called Wóksape Wednesdays online, which originally began at the Dakhota Lodge Division of Indian Works in Midtown Minneapolis. It’s a place for Indigenous folks to share a space and learn together.

“It's definitely built my confidence and worked towards stabilizing the Dakota or the Lakota language and it's also welcomed a lot of different perspectives with other languages. They’ve openly shared in this communal space. “We gather and share experiences with the community together. And we are true to ourselves by sharing all of our thoughts about every person's language journeys.”

Wakiƞyaƞ Waƞbli honors his relatives by creating, understanding, and developing kinship bonds while supporting Indigenous peoples in their language journeys—including his responsibility to his children to connect the language and culture with his relationships in the community.

“The language means everything to my well-being, to my spirituality, to my mental health, to my spiritual health, to my wellness, and to my connections. I strive to continue that with my children and share every opportunity that I have with them because they're the ones that are going to be coming up speaking, recognizing,” he says. “When I'm gone, I want my children to have as many relatives as possible. They'll cherish the lifetime of memories and their relatives will love and respect them, and honor them. As we have always provided great care for our children and family." Mitakuye Owasin.

Could you share some Dakota words and phrases?

Apaĉeĉe is the word I've always been taught for “fancy.” So back in 2014, when everyone was like, “Oh, that's so fancy,” we would use the word apaĉeĉe for something that's fancy. And then another student taught me this when we were at the Dakota language roundtable: the word “period.” A lot of people have been using the word “ye,” which is what you use at the very end of sentences if you're female. So, from time to time, they'll just be like, “period.” It's really fun to see that the language can evolve into a more modern way of speaking. It just makes it so much fun to learn.

One thing about my language journey is I write a lot; I have many notebooks full of notes. And I think it's important to realize that I have so many different ways to communicate in Dakodia or Lakoliya when it comes to an expression with the uniqueness of Dakhód. When I am no longer here, it's my children that are going to look at my books and notes and they're going to wonder, “What was my father talking about all this time? What was he saying that day?” And it'll be there for them to pick up and to understand. My favorite ways to express myself are MaLakota, which means “everything as spiritual being connected to the human experience,” and a new one is Oháƞ waná iblábde, which means, “Okay, I’m going to leave now.” Also, wólakota, which is “practicing a peaceful life.”

All Minnesotans already speak some Dakota words in everyday life. These place names are derived from Dakota traditions and/or Dakota language: Minnesota, Minnetonka, Mankato, Chaska, Chanhassen, Winona, Red Wing (named for a Dakota chief), Cokato, Shakopee, Black Dog (a park in Bloomington, named for an old Dakota village), Minnehaha Falls, Waconia, Wayzata, Owatonna, and many, many more. Why not learn more? Zitkada is bird, oti is house, ṡuƞktaƞka is horse. Keep it going!

Fall 2024 courses

- Our courses are available to both degree-seeking and non-degree-seeking students.

- The American Indian studies department offers scholarship opportunities and Minnesota residents aged 62 or older can enroll in courses for $10 a credit through the senior citizen education program.

- Not at UMN? Students at Big Ten Academic Alliance schools may be able to enroll through the CourseShare program.

DAKO 1121 - Beginning Dakota I (5 credits)

DAKO 3123 - Intermediate Dakota I (5 credits)

DAKO 3125 - Introduction to Dakota Linguistics (3 credits)

DAKO 4121 - Beginning Dakota I (3 credits)

DAKO 4123 - Intermediate Dakota I (3 credits)

DAKO 5126 - Advanced Dakota Language I (3 credits)

DAKO 5226 - Dakota Mastery I (3 credits, capstone)

AMIN 1001 - Introduction to American Indian & Indigenous Peoples (3 credits, fulfills Diversity and Soc. Justice in the US)

AMIN 1003 - American Indians in Minnesota (3 credits, fulfills Diversity and Soc. Justice in the US and Historical Perspectives)

AMIN 3001 - Public History (3 credits)

AMIN 3141 - American Indian Language Planning (3 credits)

AMIN 3201W - American Indian Literature (3 credits, fulfills Diversity and Soc. Justice in the US, Literature, and Writing Intensive)

AMIN 3312 - American Indian Environmental Issues and Ecological Perspectives (3 credits, fulfills Environment)

AMIN 3602 - Archaeology and Native Americans (3 credits)

AMIN 3871 - American Indian History: Pre-Contact to 1830 (3 credits)

AMIN 4994 - Directed Research

AMIN 4996 - Field Study

AMIN 5141 - American Indian Language Planning (3 credits)

AMIN 5602 - Archaeology and Native Americans (3 credits, fulfills Diversity and Soc. Justice in the US)

Support Dakota language study at UMN

You can support students in the Dakota language program by making a gift in any amount. This fund may be used for scholarships, awards, programming, or other uses.

Stay connected

Dakota language program on Facebook

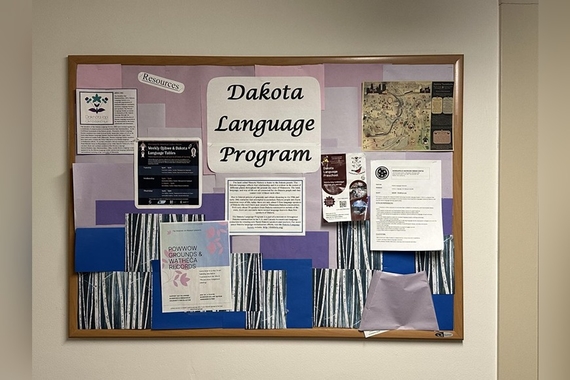

Dakota and Ojibwe Language Resources (UMN Circle of Indigenous Nations)

This story was written by Lily Zenner, an undergraduate student in CLA.