Canoes: Indigeneity, Relocation, and Maintaining Tradition

Over 1,000 years ago, Tahitian mariners crossed the Pacific to Hawaii. The expert navigators used stars and waves to help guide their voyages across the Pacific Ocean, which covers over one-third of the Earth’s total surface area and is larger than all the continents combined. In 1976, a Micronesian sailor named Mau Piailug set out to retrace that historic route by traveling from Hawaii to Tahiti, a distance of almost 3,000 miles, using the same navigational techniques of his ancestors.

As an undergraduate at the University of Hawaii, Vicente Diaz watched the 1983 documentary The Navigators, an experience that had a profound influence on the trajectory of his career.

Diaz was moved by Piailug’s accomplishment, especially because of the geographical connection. Piailug has lineage to Pohnpei, an island in Micronesia, and Diaz was born and raised in Guam, a US island territory in the region. The documentary inspired Diaz to explore the nuances and idiosyncrasies of Native peoples, and by extension, explore his own Native identity and culture.

Engaging Indigenous Practices

The documentary and Diaz’s personal connection to the people in it helped him realize that he did not know a lot about his Native culture. This “coming to consciousness,” as he calls it, continues to drive his research decades later. Diaz runs three ongoing projects centered around the building and sailing of Native canoes.

Diaz teaches a class called Native Canoes of the Pacific and the Great Lakes. The hands-on ecology course focuses on building and operating Native-style canoes, as well as studying the art of long-distance navigation. Diaz created this course hoping to “juxtapose Native watercraft and water traditions in Oceania and Native traditions in the Great Lakes.” The students use indigenous water technologies and water traditions to explore questions of indigeneity and the environment. Exposure to canoe customs allows the students to develop an individual relationship with the canoes and Native culture.

Diaz also founded a canoe program through the Department of American Indian Studies. This program combines the water traditions of Native Americans in Minnesota and the canoe and sailing traditions of Pacific Islanders to help community relations and engagement.

Climate change has caused sea levels to rise, resulting in coastal erosion and flooding, forcing groups of Native Pacific Islanders to leave their homes. That relocation could “spell the demise of their sense of who they are and their cultural practices around water,” since the move forces the loss of a familiar ecosystem. Relocating poses a threat to water navigational practices and canoe traditions.

Diaz aspires to save water and canoe traditions by connecting Native Americans of Minnesota to relocated Islanders. The Islanders want to adjust to the northern plains and its water, and Diaz wants to help them. His project will help Pacific Islanders and Native Americans use combined knowledge of the land and canoes to continue canoe building and navigation traditions that contribute to the identities of Native Islanders.

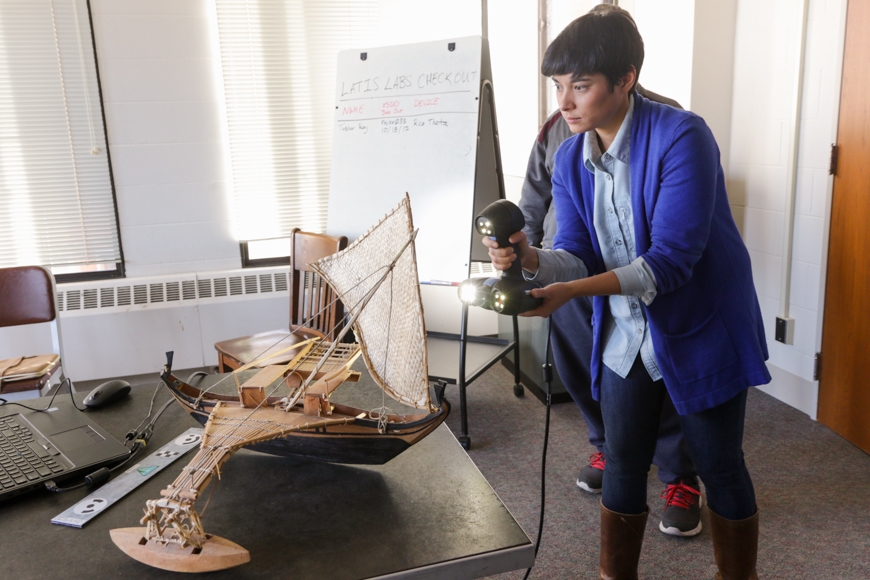

Diaz’s third project, called Digitizing Ancient Futures, utilizes augmented and virtual reality technologies to create canoes to take on simulated voyages to islands. Using virtual reality to build and sail Native canoes “address[es] cultural loss in atolls in the Pacific that are endangered because of rising sea levels,” says Diaz.

With this unique blend of traditional knowledge and state-of-the-art technology, Pacific Islanders who were forced to leave their homes are able to create islands that are interactive and maintain a relationship with the land.

Unstuck

Professor Diaz’s interest in canoes, traditional knowledge, and navigation is rooted in concepts of mobility and travel as ways to redefine how people talk about Nativeness.

“I think one of the sins of settler colonialism was to define Natives as stuck in certain places, including stuck in the past, and to confine Natives to specific places, like reservations, like romanticized ideas of nature,” Diaz says. “But when you understand Natives in terms of travel and mobility, you understand that Natives have traveled long before Europeans came. They were constantly moving.” Diaz’s passion and dedication to his work have helped him to anchor Native identity and culture on canoes.

Navigating the vast Pacific Ocean is no small feat, and the interconnectivity between Pacific Islander culture and water traditions makes continued navigation a central point of concern and pursuit for Diaz.

Continuing canoe and navigation practices, despite necessary relocation, will ensure the endurance of a people whose history and present spans distances of thousands of miles. Diaz’s three canoe projects work together to transcend stereotypes, to maintain a tradition that is closely linked to identity, and to help people transition to the “Land of 10000 Lakes.”

This story was written by an undergraduate student account executive in CLAgency. Meet the team.