Genetics Lab to Revisit the Past

Today with personal DNA testing kits and in-depth health screening, accessing genetic information is easier than ever. The anthropology department, however, is advancing our understanding of ancient genetics through anthropological genetics lab. By integrating principles of genomics, archaeology, and anthropology, the lab uses surviving genetic material to reconstruct histories and draw connections between ancient and modern civilizations. Lab Manager Dr. Carrie Miller and Principal Investigator Dr. Maria Nieves-Colón discuss this project and its goals of revisiting understudied populations to better understand “what it means to be human.”

What question is at the heart of your project?

Our anthropological genetics lab is pursuing multiple projects that apply ancient DNA research techniques to explore what it means to be human. This means using information contained in genetic material from archaeological remains (most frequently bone and teeth) to reconstruct the histories and experiences of peoples who lived in the past and understand how they connect to present-day communities. We are especially interested in tracing ancient migrations and population encounters (and the genomic impacts of these encounters), specifically resulting from colonization in the Caribbean and Latin America.

How would you describe your project?

Our lab focuses on answering questions related to human population history by integrating insights from genomics, archaeology, and anthropology. We seek to understand the impact of transformative processes, such as migration and colonization, on the genetic variation, culture, and health of historically understudied populations in the Caribbean and Latin America. We take an integrative approach to reconstruct the histories of these communities in order to characterize their adaptive evolution. To achieve this, we generate and analyze ancient and modern human genome datasets to reconstruct past migration and the resulting introduction of new genes, trace connections between past and present populations, detect selection signals, and investigate the impact of adaptive variation on health and disease susceptibility.

How does your work reflect, confront, or otherwise call attention to problems facing our society?

In our research, we strive to dismantle colonial narratives about the past by calling attention to the experiences of populations that have been marginalized or misrepresented in history. By doing so, we hope to contribute to a broader understanding of human biological variation. We accomplish this by working in partnership with descendant communities in the Caribbean and Latin America so that their voices are heard and considered within our research designs. While our genetic methods help unearth the histories of these populations, the living descendants contribute to decisions of how these stories are told. They help develop research questions that better consider the potential ethical ramifications of our methods and gain experience in the methods we apply through workshops. Our transparency ensures that stakeholders understand what we are doing and why we are doing it every step of the way.

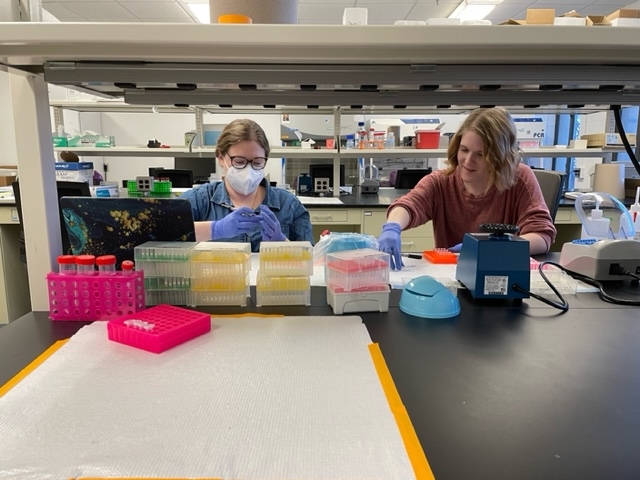

Furthermore, our lab includes staff members and trainees at all levels. This means that in addition to our research goals, we are also a training center for people with different academic and personal backgrounds. Our lab even extends beyond the University; our first workshop was offered in Puerto Rico in the summer of 2022 in collaboration with faculty colleagues at the Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico. Students in our lab receive training in genomics and STEM that can be applied beyond the time they spend in our lab. Genetics is everywhere now. It is a major focus of biomedical research, forensics, and even direct-to-consumer testing. We aim to equip all members of our lab with the tools to critically evaluate what DNA information can and cannot say about their health, identity, and ancestry to better understand themselves and others around them.

Does your project have an outreach component? If so, could you describe it?

Our lab is committed to sharing contributions and developments in the field of ancient DNA and paleogenomics through science communication. We report the results of our research to local populations and institutions with which we collaborate and who have a stake in our research. The descendant communities we work with may be impacted by ethical, legal, and social issues (ELSI) that arise when studying human populations. As partners in our research, we believe it is vital to present our research projects to stakeholders in the sites where we work. This includes translating our research and results into accessible presentations, videos, animations, and artwork.

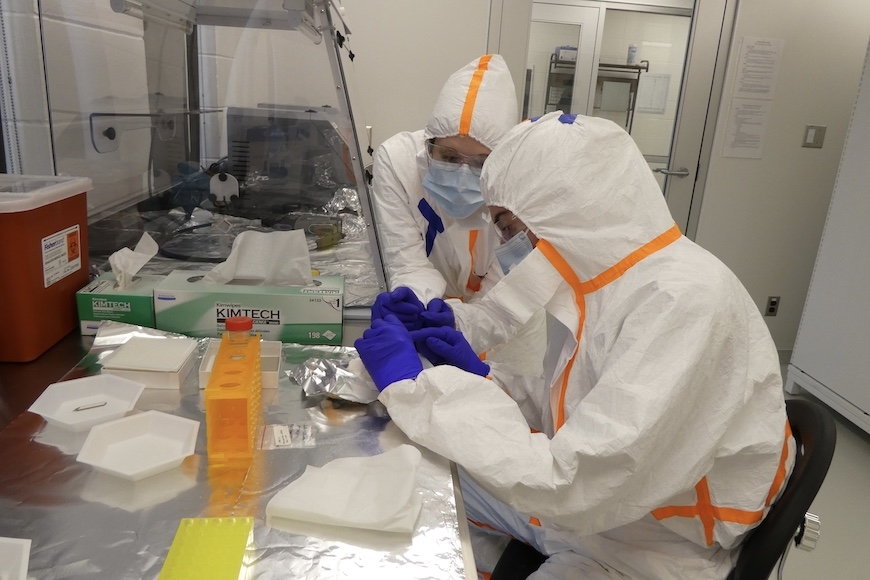

For example, two of our graduate students used a GoPro to record their lab work and produced a short video highlighting the main steps of sampling and extracting DNA from ancient human remains. The video was later presented at a stakeholder meeting so that the community members could see what we we’re doing with the remains of their ancestors as if they were right there with us. We strive to engage in constant communication with descendant communities and stakeholders to ensure that all possible ELSI outcomes are considered before publishing work that might otherwise cause harm if these voices were not given the space to be heard. This example is just one way we achieve this.

In addition to working closely with Latin American and Caribbean communities, we also provide local students with opportunities to learn about what it means to do ancient DNA research. This research helps them understand what a future in this particular field of STEM might hold. Through classroom and outreach opportunities, we hope to teach students how genetics and evolutionary thinking impacts their daily lives, in everything from finishing a course of antibiotics to interpreting the results of an ancestry test.

Our lab members all participate in outreach and education, integrating genetics with anthropology through a variety of directed topics, including epidemics and human evolution, fundamentals of anthropology genetics, and introductory material on human evolution. We are constantly thinking about how to teach and learn from each other, and we provide time, space, and tools to those who want to learn more about studying ancient DNA.

What does your research look like? What methods do you use?

Because the process of obtaining ancient DNA is inherently destructive, we first work in partnership with descendent communities, archaeologists, and anthropologists to consider how best to ethically sample remains. Once we have reached a consensus with all stakeholders, we then sample the dense tissues shared with us, such as teeth and bone, as they are most likely to survive the decomposition process and preserve DNA after the death of an individual. To accomplish this, we have to destroy a fragment of bone or teeth in order to isolate and sequence the DNA that is preserved inside. However, once we have destroyed that fragment, the piece of tissue is gone forever. This means that in every stage of our research, we have to carefully consider the ethical ramifications and make sure that we have consulted with stakeholders, such as descendent communities, museum curators, and other scientists before engaging in destructive sampling.

Despite its destructive nature, we do ancient DNA analysis because it can reveal novel information that is often not readily available. By combining field, museum, and laboratory work in addition to collaborating with descendant communities, we can reconstruct ancient migrations and encounters between peoples, examine patterns of kinship and relatedness, and uncover information about ancient health.

What's next?

Our lab is growing! With that comes several new and exciting research projects as we expand into new topics (e.g., human health and disease, microevolutionary processes in humans), new regions (e.g., Florida and Mexico), and new research protocols (e.g., sampling DNA from other parts of the skeleton and improving computational techniques). We are currently working on a project that uses ancient DNA to investigate the histories of enslaved African and Afro-descendant peoples who lived and worked at Hacienda La Quebrada, a historic sugar plantation located in the San Luis district of the Cañete Province, Peru.

Working with this same population, two of our current graduate students will expand the scope of this study. Laura Pott will assess how the human genome changes in response to historical processes like colonization. In doing so, she hopes to determine the degree to which the introduction of new genetic material in a population (i.e., admixture) can transform the adaptive evolution of our immune systems.

Jaime Zolik aims to reconstruct health and disease patterns in 18th-century La Quebrada by combining ancient DNA sequencing of the individuals in the burial ground with the analysis of historical texts that describe the conditions that may have allowed infectious diseases to thrive. If she is able to identify the presence of disease-causing pathogens, then she will compare past and present genetic sequences to examine how these pathogens have evolved over time. Both research projects will further contribute to our lab's efforts to study the evolution of human health and disease, which is often difficult to assess over deep time without the assistance of genetic techniques.

Outside of Peru, our work continues in regions of the Caribbean, Latin America, and even North America. We are starting a new project that will use ancient DNA to characterize the genetic diversity of the first human communities in the Caribbean islands in order to address questions related to their origins and interactions as well as their legacies and connections to present-day Caribbean peoples.

Related to this project, one of our undergraduate researchers, Emma Ulrich, is collaborating with researchers from Vanderbilt University and using genetic data gathered from modern DNA to explore the genetic ancestry of individuals who identify as Afro-Puerto Rican. Her work contributes to the vital stage of genetic research that comes after the many steps of DNA extraction, purification, and amplification: analyzing the resulting genetic data. Her broader goal is to improve computational resources by developing a pipeline for analyses that can be applied to both modern and ancient DNA data through the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute (MSI).

Our other undergraduate researcher, Margaret Hassler, is also contributing to the development of methods that are new to our labs. She is recovering ancient DNA from two unidentified victims of the 1928 Hurricane in Okeechobee, Florida. In an effort to repatriate the remains, she will develop protocols for extracting ancient DNA from the petrous portion of the skeleton as opposed to sampling from teeth.

Finally, our newest graduate student, Miguel Contreras Sieck, will address questions related to the timing and pattern of the populating of the Americas, and the subsequent adaptations to new settings. He will explore genotype-to-phenotype interactions by incorporating ancient and modern DNA methodologies in combination with 3D scanning to explore microevolutionary patterns in communities living in the Basin of Mexico. In doing so, he hopes to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the complexities of our species’ microevolutionary history.