POLICY BRIEF: Current Workers and Retirees

I. INTRODUCTION

This brief continues our example of applying principles of economic analysis to evaluate the tradeoffs in public pension policy. Our earlier briefs proposed that there are five main constituencies affected by public pensions policy. The first of this series of briefs identified the five main constituencies, and proposed analyzing the effects of closing a public DB plan to new hires. That brief went on to discuss the implications on new hires of replacing the DB plan with a DC plan. The second in this series of briefs discussed a second constituency, future generations. That brief analyzed the impact of legacy debt from the current DB system on future generations.

In this brief, we consider the impact of closing the DB plan on the remaining three constituencies: retirees, current public employees and taxpayers. We begin by identifying the four main policy choices, and continue by showing the impact on each of these constituencies of different choices.

As in the other two briefs, we do not propose a specific policy in this brief. Rather, our goal is to identify the key tradeoffs and analyze the impact of these choices. It is worth remembering that with underfunded pension plans, there are no obvious choices that will make all constituencies better off. Policy makers must identify tradeoffs and make choices accordingly.

II. MAIN POLICY CHOICES

Closing a public DB to new participants has the effect of reducing the number of choices open to policymakers. Our analysis will focus on four main choices. Many of these are self-explanatory, as are their effects on each constituency. Our four policy choices are:

- Freeze, or reduce, cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) for retiree benefits

- Eliminate any potential for future, unexpected, retiree benefits (the so-called “13th check)

- Commitment to paying the Annual Required Contribution (ARC)

- The contribution split between current workers and retirees

It should be noted that the commitment to paying the ARC, combined with the ability of the fund to achieve their target investment returns drive whether the DB pension plan creates a debt for future generations. Thus, the main tool for policymakers who are concerned about this legacy debt is the commitment to paying the full ARC.

Notice that one variable that we haven’t included is the investment return on a fund’s asset portfolio. The main reason that we haven’t included it is because policymakers cannot control actual investment returns, even though they can control the target that they set for the returns on their investment portfolio. Moreover, each of these four choices feeds back into the target return. For example, lower target returns imply higher contributions. In our view, policymakers should focus on the policies they can actually influence, and then determine the target return on the investment portfolio.

III. Freeze COLAs

The first policy we’ll consider is reducing COLAs. Although pension benefit guarantees are stated in nominal terms, many states and municipalities have offered COLAs (either full or partial) to their retirees as a mechanism to maintain real. Purchasing power. The impact of reducing COLAs is very straightforward. Because nominal purchasing power is fixed, real purchasing power during retirement declines when the COLA is reduced. Decreasing real purchasing power affects both (a) the present value of real consumption expenditures and (b) the economic welfare of those expenditures. Moreover, reducing COLAs decreases welfare not just for retirees but also for current workers. The main reason for this welfare reduction is because of its impact on lifetime income and spending decisions.

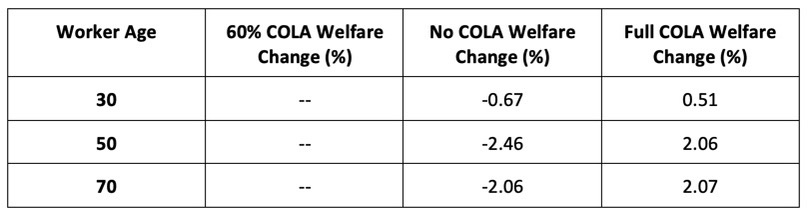

These points are illustrated in Exhibit 1 below. The exhibit shows the present value of consumption and economic welfare for three ages of public workers (a 30-year old, a 50-year old and a70-year old retiree) under three COLA regimes (a COLA paying 60% of inflation, no COLA, and full COLA). As is evident from the exhibit, all public workers are adversely affected on both measures when the COLA is eliminated. Similarly, all public workers gain when the COLA is increased. We chose not to show the impact of COLAs on private sector workers here. However, the impact on their welfare is the exact opposite- private workers gain when public sector worker COLAs are decreased, and lose when they are increased.

The financial implications for current public employees and retirees of reducing COLAs are self-evident. Equally, it should be evident that taxpayers gain when COLAs are reduced, as real expenditures on pensions decline. This second point leads to a relevant policy implication: for underfunded pension plans, reducing COLAs becomes an attractive mechanism for policymakers to reduce the fiscal burden of underfunded pensions without (potentially) running afoul of the constitutional protection of pension benefits.

V. Eliminate unexpected benefit optionality

One important feature of DB plans has been the ability to re-negotiate pension benefits, and/or offer an unexpected extra retirement payment to retirees. The former has occurred during salary and benefit negotiations between public union officials and policymakers. The latter has happened during periods of pension funding surplus. The broad feature of re-negotiating retirement benefits is never guaranteed, meaning that it has an option-like characteristic to it. In the terminology of option pricing, pension beneficiaries have an option on future benefit increases. This option is underwritten by taxpayers.

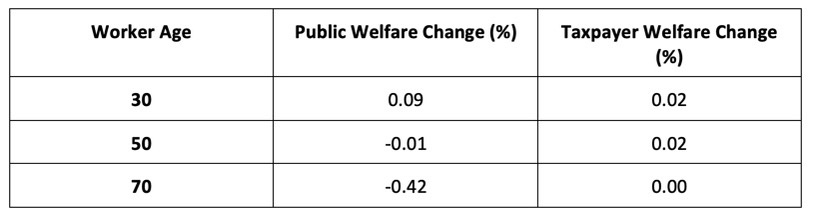

Not surprisingly, eliminating the option on future retirement benefits reduces the expected present value of consumption for public workers and retirees, and increases it for taxpayers. This point is illustrated in Exhibit 2. The exhibit uses the same classifications of public workers as in Exhibit 1 (i.e., a 30-year old, a 50-year old and a 70-year old retiree), plus taxpayers.

Although the impact of reducing or eliminating unexpected pension benefits is self-evident, there are nevertheless two additional points to be made. First, increasing pension benefits during contract negotiations is a second-best solution for public workers. According to standard lifecycle models, workers would prefer increased wages during working years and constant retirement benefits, versus constant wages and increased pension benefits. Second, the second-best solution is preferred by policymakers because it reduces short-term fiscal pressures.

VI. Commit to Making Required Pension Contributions

In our earlier work, we documented that over the past two decades, contributions have averaged around 83% of the amount required to maintain full pension funding. Naturally, there is variation across states in the regularity of making full pension contributions. Some states (e.g. Wisconsin and South Dakota) have a long history of making pension contributions. Nevertheless, on balance most states have not done so.

The main reason that pension contributions are important is because they (along with investment returns) affect the solvency of the pension plan. Fund solvency requires that pension contributions be made, even when investment return targets are met.

It turns out that analyzing the welfare consequences of committing to make required pension contributions depends on two additional policy choices. The first is the commitment to paying the ARC (which affects legacy debt), and the second is the split between taxpayer and public worker contributions. These will each be discussed in the next section.

VII. Level of Legacy Debt and Contribution Split

In the previous brief, we showed (and not surprisingly) that future generations’ welfare improves when the level of legacy debt decreases. In that brief, we illustrated this point with three specific policy choices from today’s policymakers. All three cases assumed that the DB plan is closed to new entrants. By closing the DB plan, the level of legacy debt depends on (a) the commitment to paying the ARC; (b) the level of optionality in pension benefits and (c) whether target returns are met. In all of our examples we assumed that the level of optionality in pension benefits was eliminated. For our first example, we assumed business-as-usual, i.e. 83% of the ARC is paid and target returns are not met. In the second example, we assumed that 100% of the ARC is paid and target returns are not met. In the final example, we assumed that the ARC was fully paid and that target returns are met. Only in the third case is there no legacy debt left for future generations.

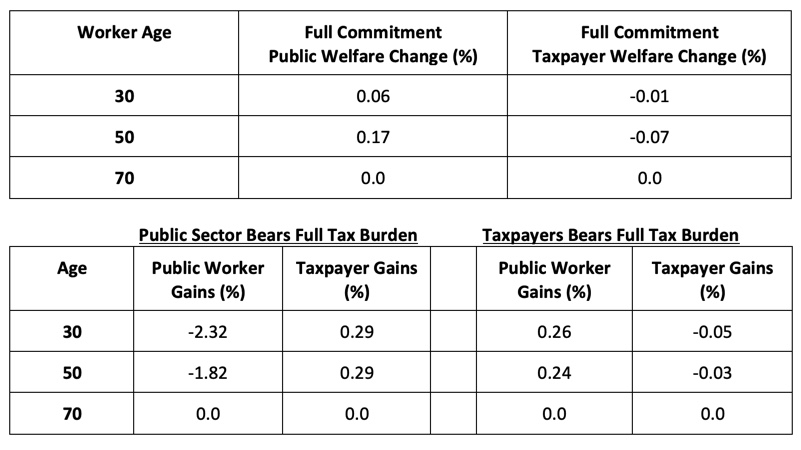

The impact on each of these choices on current taxpayers and current public workers depends on how the contributions are split between these two groups. The limiting cases are very straightforward. At one extreme, policymakers can choose to hold public worker wages and contributions fixed, and pass on any increased contributions to taxpayers in the form of increased taxes. At the other extreme, policymakers can choose to hold taxes and public sector wages fixed, and pass on contribution increases to current public workers.

Exhibit 3 shows the impact of these policy choices for each of our three commitment strategies (which are also choices about legacy debt). As in the earlier exhibits, we consider the impact on three ages of public workers and taxpayers. Not surprisingly, welfare increases for all constituencies when the level of legacy debt increases. Taxpayer welfare decreases when they pay a higher share of contributions.

An interesting result is the impact of the contribution split on retirees. In this example, retirees are indifferent as to how the contributions are split. The main reason for this is because our model is set up so that retirees (a) receive no labor income and (b) aren’t taxed on investment income. However, when retirees are taxed on investment income, then there will be a clear preference to shift the burden to current workers.

VIII. Conclusions

This brief discussed the impact on current and retired public workers, and taxpayers of alternative pension reform policies. Our examples maintained the assumption from earlier briefs that the public DB plan is closed to new entrants. Closing the plan simplifies the choices available to policymakers to (a) how much legacy debt is left to future generations; (b) how current pension contributions are to be split between current workers and taxpayers; (c) the level of cost-of-living adjustments provided to retirees, and (d) whether retirees can receive unexpected pension benefit increases.

Our analysis focused on considering the impact on economic welfare of different choices. Not surprisingly, when COLAs and retirement benefit optionality are reduced or eliminated, public worker and retiree welfare decreases and taxpayer welfare increases. When the level of legacy debt decreases (brought about by a commitment to full pension funding), then the welfare impact depends on which group pays the increased contributions.

As with our earlier briefs, we do not favor one policy choice over any other. Rather, we chose these examples to illustrate how our models can be applied. Furthermore, by choosing to use economic welfare as our measure, we can make comparisons across multiple constituencies. Our next brief summarizes the results of our policy experiment on all five constituencies.

AUTHORS

Kurt Winkelmann is a Senior Fellow at the University of Minnesota where he leads the Heller-Hurwicz Economics Institute’s Pension Policy Initiative. He is also founder and CEO of Navega Strategies, LLC. Prior to starting Navega, he was Managing Director and Global Head of Research at MSCI and a Managing Director at Goldman Sachs Asset Management. Kurt earned his Ph.D. in economics at the University of Minnesota, and is the chair of the Heller-Hurwicz Economics Advisory Board.

Jordan Pandolfo worked as a graduate research assistant before earning a Ph.D. in the Department of Economics at the University of Minnesota.