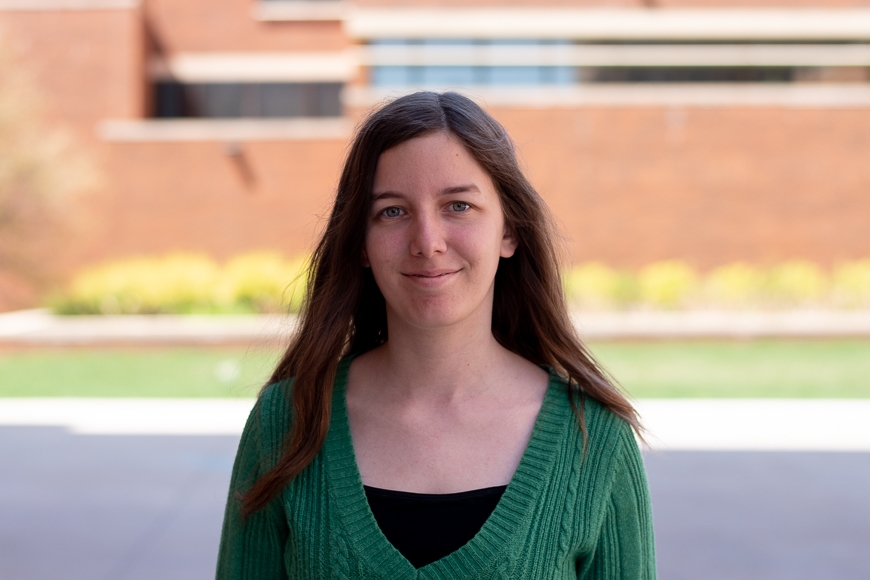

Conway and Locke on Personhood

What makes someone a person? How is someone the same person today that they were yesterday? These questions might bring to mind the seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke, who famously raised them in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Locke, however, was not the only early modern philosopher to grapple with such questions. According to philosophy graduate student Heather Johnson, Anne Finch Conway also investigated the nature of persons and their persistence in her Principles of Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy. But Johnson points out that Conway has been largely overlooked by scholars of the early modern period until relatively recently, leaving her reflections on personhood, identity, and persistence unexplored and underappreciated. To remedy this, Johnson plans to devote the first part of her doctoral dissertation to reconstructing Conway’s theory of personhood and comparing it to Locke’s more familiar theory.

Is a Rock a Creature?

Johnson began to wonder about the role of persons in Conway’s philosophy in Fall 2017, when she took Jessica Gordon-Roth’s course on Conway. She explains that getting clear on Conway’s conception of personhood is no easy task. “It’s a bit of a mess,” she says, “not least because she doesn’t explicitly use the terminology of persons or personhood.” Whereas Locke provides a (more or less) straightforward definition of “person,” Conway does not seem to introduce any synonymous term. But Johnson maintains that Conway does have a theory of personhood, even though she might not formulate it in the Lockean vocabulary so familiar to us today. “She’s talking about a lot of the same things as Locke,” says Johnson, “and it seems to me that the easiest way to talk about these ideas is through the lens of personhood.”

Though Conway doesn’t speak explicitly of “persons,” she does talk about “creatures” and their capacities. For Conway, creatures are all those entities created by God— everything from animals to rocks, from human beings to angels. “All creatures are composed of living spirit for Conway,” explains Johnson, “but they might have very different capacities.” These differing capacities arise from the various ways in which living spirit can be organized. Angels and human beings, for example, have certain capacities—such as rational thought—that rocks lack, since the spirit composing angels and human beings is more ethereal than the comparatively dense, crass spirit composing rocks. As far as what these sorts of capacities are, Johnson admits that she is not yet sure, but she suggests that they might be something like the capacities we often associate with personhood, such as rational thought or exhibiting complex emotions.

The Threshold of Personhood

Immediately, we encounter a crucial difference between Conway’s conception of personhood and Locke’s; while Locke provides a fairly clear-cut definition of “person,” under which any given entity either falls or not, Conway’s picture seems to allow for a more indeterminate conception. “There is an inherent vagueness to Conway’s spectrum of creatures,” explains Johnson, “and it’s possible this vagueness also applies to her theory of personhood.” Rather than laying out a set of definite criteria for deciding one way or the other whether a given creature is a person, Conway’s views might suggest a kind of gradient of personhood, in which some creatures are more or less of persons than others. As Johnson points out, Conway discusses horses and dogs at length and notes that such creatures share a number of capacities—rational thought, memory, emotion—with human beings. Thus, on Conway’s view of personhood, these creatures could be more of a person than a rock but less of a person than an angel or a human being.

But Johnson suspects that there is a certain threshold of personhood for Conway, a point on the spectrum of creatures separating persons from non-persons. However, unlike for Locke, Johnson suggests that there might not be any necessary conditions for passing this threshold. In other words, she thinks that for Conway there are no capacities that a creature must have in order to count as a person. Instead, Johnson speculates, there might be only sufficient conditions for personhood—capacities that guarantee a creature’s being a person but are not in themselves required for it. “Certain capacities—perhaps rational thought or exhibiting complex emotions—might be sufficient to cross the threshold of personhood,” she explains, “but that is not to say that any one of these capacities is required to be a person.”

Where the Theories Diverge

But where Conway and Locke really part ways is not on the issue of persons but on the nature of their persistence. “Conway and Locke disagree pretty drastically in how the persistence of a person is supposed to work,” says Johnson. For Locke, a person’s remaining the same at different places and times is closely connected to memory and consciousness; someone’s being the same person today as she was yesterday consists in her possessing the same consciousness at both times, which is itself intimately connected to her memories.

For Conway, on the other hand, consciousness and memory play no role in the persistence of creatures. As Johnson points out, Conway’s conception of persistence is deeply interwoven with her view of transmutation, according to which all creatures, upon their death or destruction, are reborn as new creatures. “Nothing really dies for Conway, but is rather recycled back into the world through transmutation,” explains Johnson. For Conway, it’s not having the same consciousness or memories that accounts for a person’s persistence but rather having the same soul, an entity that inheres in each creature and accompanies it from transmutation to transmutation.

For Conway, as for Locke, the persistence of persons is not merely a metaphysical question but has ethical relevance. “According to Conway, every creature is a moral agent with a law inscribed into its nature by God,” explains Johnson, “and what sort of entity a creature will be reborn as upon its death or destruction is determined by its accord or discord with this moral law.” A less than moral human being might become a slug, for example. An exceptional human being might be reborn as an angel. Thus, for Conway, the persistence of creatures is essential to their receiving appropriate Divine reward or punishment. “Conway takes it to be very important that creatures remain the same over time in order that they receive Divine punishment or reward in accordance with how they’ve exercised their moral agency,” says Johnson. But she is quick to point out a potential problem with this picture—one Locke certainly could have raised: If a creature’s memories are destroyed in transmutation, how can the reborn creature be held responsible for actions of which it has no memory? Does not Conway’s view, Johnson asks, in a distinctively Lockean phrase, confuse punishment with misery? Johnson provides no definitive answers to these questions, but simply raising them illuminates Conway and Locke’s shared concerns and divergent approaches to the issues of persistence, morality, and Divine punishment.

But despite their overlapping concerns and questions, the reception of Conway and Locke among historians of philosophy could not be starker. Though each was an active, engaged thinker of the early modern period, only Locke would be incorporated into its canonical figures, leaving Conway’s thought largely overlooked by subsequent generations of philosophers. “The way the canon has been constructed—focused on only a few, purportedly most important, figures—obscures what was actually going on at the time,” Johnson remarks. In particular, the exclusion of women philosophers such as Conway from the early modern canon creates the false impression that women simply weren’t interested in the questions which motivated the likes of Descartes, Locke, and Spinoza. But as Johnson is quick to point out, there were a number of women grappling with the same questions, engaging their male colleagues as equals through discussion and correspondence. “Yet even as these figures were doing work very similar to that of their male counterparts,” she adds, “they’ve been erased out of the history of philosophy.” Johnson, therefore, emphasizes the importance of reconstructing and reappraising the work of these overlooked philosophers: “Missing out on the views of these early modern women only gives us an impoverished understanding of the period.”

This story was written by an undergraduate student content creator in CLAgency. Meet the team.