We Who Are AA&AS

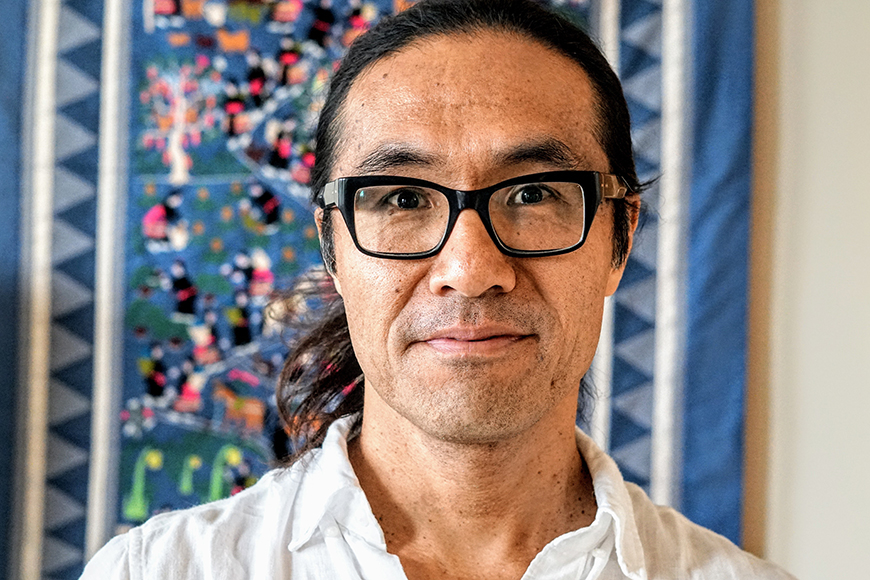

Associate Professor Yuichiro Onishi

My name is Yuichiro Onishi. I teach in the Department of African American & African Studies (AA&AS) and Program in Asian American Studies at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. I just stepped in as chair of AA&AS. I want to thank my dear colleague Tade Okediji for chairing AA&AS for the last four years. I will be following in his footsteps to go on strengthening our intellectual rigor.

A Transformative Education

It is a great honor to lead the very academic unit that helped shape my political consciousness. AA&AS was one of the key nodes. Back in 1996-99, I was a graduate student in history who transgressed the boundaries of traditional disciplines.

I went to AA&AS on the eighth floor of the Social Sciences Building.

Rose Brewer, now my colleague, was one of my teachers. We read Patricia Hill Collins’s Black Feminist Thought (1990), Paul Gilory’s The Black Atlantic (1993), Joy James’s Transcending the Talented Tenth (1997), and many more, both classic and cutting edge. I also took seminars with Angela Dillard and David Roediger. The first week of reading in Dillard’s African American history seminar was W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction (1935), plus Elsa Barkely Brown’s essay “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom” (1994). In the directed reading group led by graduate students and Roediger, we took up CLR James’s corpus. Many of us were involved in union organizing, too, with the Graduate Student Organizing Congress (GradSOC). I found incredible fellowship, and all these spaces of learning presented a very different language with which to talk about freedom, including its problems, contested history, and alternatives.

We approached Black thought and history with a kind of seriousness that helped chart the process of becoming. Just to be clear, it had little to do with identity formation. Rather, this world of becoming was about knowledge, engaging with it to expand the mind. We read, discussed ideas, and listened to each other. I, for one, learned how to think, politically and historically, like an internationalist.

We were in the Clinton years (1993-2001) and contending with the interconnectedness of various forces: the fast erosion of the welfare state and attendant social goods; mass criminalization; rapaciousness couched in terms of triumphant colorblind meritocracy; and globalization that furthered underdevelopment and impoverishment at home and the world over.

AA&AS encouraged new formations against these currents. Black thought was tenacious, and the experience was transformative. I bring this memory back for a reason.

A Radical Revolution of Values

In a given moment, however small, self/structure undergoes what Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called “a radical revolution of values.” In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, we are occupying such a moment. We are rapidly indexing where we are, what we are, and who we are. Multitudes of people have taken to the streets to engage in concerted activity, mutual aid, collective self-defense, solidarity-building, and direct democracy at the grassroots, day in and day out. In fact, many of the organizers and activists have been moving from strength to strength, at once, since the 2014 Ferguson uprising and a wave of protests against the police state that followed in 2015-16 and long before all the contemporary insurgencies. There is a longstanding tradition of historical struggles pulsating in the present. AA&AS possesses such a pulse.

Similarly, fifty years ago, in the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, key advances were made. AA&AS’s emergence, we know, is tightly bound up with the vortex of the late 1960s. On January 14, 1969, the members of the Afro-American Action Committee and its supporters carried out direct action against the University of Minnesota. They took over Morrill Hall. Black student leaders, the late Rose Mary Freeman, Horace Huntley, and many others, were tired of the University's tepid responses to their demands to radically transform a “historically white” land grant institution.

Much was at stake then. The US war in Viet Nam was raging, and antiwar resistance was galvanizing. Black Power was staging a new politics. Dr. King, who carried forward the Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s and 1960s, too, was issuing a call for “Freedom Now,” but with a very different tenor. He spoke out against the war, poverty, systemic impoverishment, and racial injustice, and framed the nucleus of the pressing problem in global anti-capitalist and anti-racist terms: “the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism.”

The day before Dr. King was gunned down, he was in Memphis to stand with 1,300 sanitation workers struggling for the dignity of labor and workers’ rights and democracy. He told the crowd in the address remembered as “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” that he was happy to be living in the moment where “the world is all messed up.” He said, “The nation is sick, trouble is in the land, confusion all around.” All the while acknowledging that “that’s a strange statement to make,” he explained poetically that “somehow...only when it is dark enough can you see the stars.” His vision of new futures, or revolutionary change, was dialectical.

He was specifically referring to new directions engendered by struggles of sanitation workers in Memphis and mass movements for democratization all over the world. “The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis Tennessee, the cry is always the same: ‘We want to be free.’” His message was that what better place than where we were in Memphis to start what he called “the human rights revolution.” He said, “Now I’m just happy that God has allowed me to live in this period, to see what is unfolding. And I’m happy that he’s allowed me to be in Memphis.”

The day after this address, Dr. King was murdered.

The Struggle at UMN

The Monday after, amid the conflagration in cities across the nation, the Afro-American Action Committee issued the following seven demands to the University of Minnesota. John S. Wright, Professor Emeritus of African American & African Studies and English, was a principal writer.

- We want the establishment of at least 200 full scholarships made available to the graduating class of Black Minnesota high school students this year.

- We want full consideration of the proposal to eliminate tuition for underprivileged Black high school students.

- We want the establishment of guidance counseling and recruitment agencies especially geared to the needs of Black students.

- We want the establishment of a board to review the policies of the athletic department toward Black athletes.

- We want serious consideration of the possibility of using Martin Luther King’s name for the new West Bank library.

- We want a representation of Black students on major University policy determining groups.

- We want the educational curriculum at the University to reflect the contributions of Black people to the commonwealth and culture of America.

For over six months, these seven demands remained unmet by the president’s office. Such was the context behind nonviolent political action called the Morrill Hall Takeover, the beginning of the “human rights revolution” at the University of Minnesota. This struggle is far from over. The student struggles in various formations in recent years—from Whose University? (2010-2011) to Whose Diversity? (2014-2016) to Rename/Reclaim (2017-present)—have called out institutional and structural harms done to Black and minoritized students and their communities and presented radically different ways of knowing, being, and banding together.

I bookend these moments of violences and deaths—then and now—to make it clear that in these times when multiple crises are converging, from COVID-19 to policing to economic, AA&AS will be, as in the past, a site of becoming and possibility and of transformative education.

Where are we now after more than a half-century?

What are the demands for our time?

What do Black visions look like?

Our Commitment

We who are AA&AS are always here to respond to myriad political challenges still unmet. Our faculty are stellar teachers and engaged scholars. We are trained in history, comparative literature, sociology, political science, economics, music, critical ethnic studies, archeology, ethnohistory, and cultural studies. We center African and African-descended peoples’ lives, livelihoods, pasts, sociality, struggles, politics, artistry, poetics, critical imagination, and worldliness to transform the whole knowledge structure created and perpetuated through domination. What we do becomes flashpoints.

Dear Students, Cultural Workers, Organizers, Educators, and Community Members:

We welcome your lived experiences and passion for knowledge, justice, and curiosity; steadfast engagement to become an incubator to bring critical awareness to systemic racism and initiate fundamental changes, both institutional and structural; and deep desire to share and learn from stories, aesthetic sensibilities, experiences, and histories of global African peoples to scale up the tradition of our own struggles—all in hopes of articulating a different language of freedom to give forms to new futures.