The Forgotten Women of Animation

When you think of animated films, which ones come to mind? Frozen? The Lion King? Maybe Up? Rarely do you think of films created by female animators, whose work has been overshadowed by that of male-dominated, major animation companies like Disney and Pixar, especially when it comes to creative control over films.

Recognizing a hole in the history of animation, Vanessa Cambier, a PhD candidate in the Comparative Studies in Discourse and Society program in the Department of Cultural Studies & Comparative Literature, decided to dedicate her dissertation to the study of female-animated films. Creative and politically-charged, these films are not your average Disney movies.

The Lack of Recognition

Cambier developed her interest in feminist film topics during her undergraduate career at the University of Minnesota, majoring in cultural studies and minoring in studies in cinema and media culture, as well as gender studies. Then, in 2015 as a graduate student, while working on a summer research project on experimental female filmmakers, Cambier further found an interest in experimental female animators. “Each semester, the project grew a bit more and ultimately became my dissertation topic,” she says. Today, her research focuses on female filmmakers from the 1970s to now, who use experimental animation to critique gender politics.

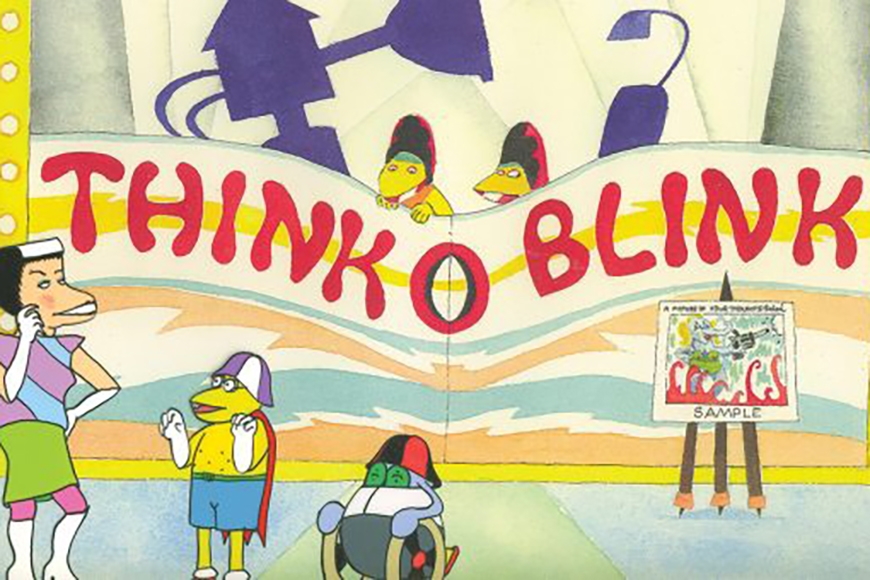

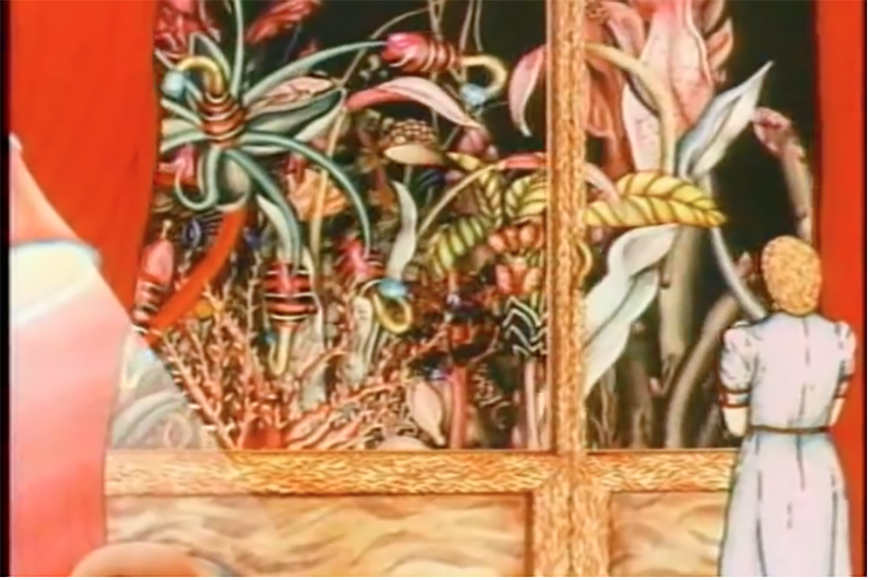

The early animators she studies, such as Sally Cruikshank and Suzan Pitt, worked primarily in the 1970s and ‘80s, and used animation in unconventional ways to break into the avant-garde scene, which was dominated by men at the time. Their films are considered experimental because they were produced outside of the studio system and are non-narrative in structure, opting to focus on concepts and construction rather than scripts and plot.

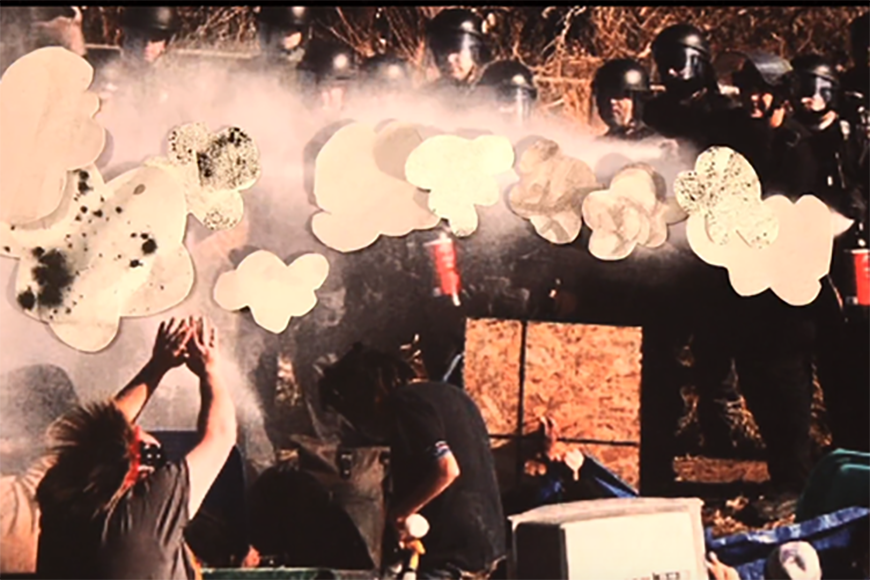

Cambier has found that Pitt’s and Crukshank’s successors, modern female animators, use many of the same techniques for storytelling and political protest. This is evident in more traditional animation styles, like that of Lisa Hanawalt, creator of the dark comedy series BoJack Horseman, as well as in more unexpected forms of animation, like that of Martha Colburn, who combines images from modern political movements with outdated and stereotypical images, especially of indigenious people, from history textbooks.

Despite novel contributions to the field of animation that still influence animators today, these female animators are still battling for recognition in the film industry and academia, 50 years later. Cambier argues that the combination of film form and gender in these animated works creates a powerful critique of life under the patriarchy, which has been overlooked. She says, “these films have been fundamentally misrecognized in both feminist film and animation scholarship.”

Advocating for Deeper Analysis

Wanting to bring well-deserved recognition to these animators and their work, Cambier set off to retrieve as many female-created films as possible. By scouring the internet and interviewing animators, she discovered an immense amount of animation made by women, and built her own library of female-animated films in the process. “Bringing things together in this project is my own attempt at a type of ‘archive,’” she says.

In her analysis on how the films are represented in the media, Cambier found that these animated films are often pigeon-holed into broad categories like “women’s animation,” and not viewed seriously for their stylistic or thematic elements.

“Scholarship about these films paints them with broad strokes and often focuses on general narrative themes such as ‘female experience.’” She argues that these generalizations overlook the way these films use experimental animation to make a visual statement on stereotypical representations of women. Instead, Cambier wants to see female-animated films categorized based on their content and construction rather than just their gender.

Fortunately, Cambier has found that her research has the power to break down preconceived notions about female-made films. “The shift is that people who read my work, hear a talk, or see these films begin to embrace the notion that women’s animation is often much weirder, more imaginative, and darker than expected,” she says.

Introducing Audiences to Experimental Animation

Cambier wants more people to watch experimental and independent films made by women, and hopes these films will change the way viewers think of female filmmakers and their work. “I want to expand notions of feminism and feminist films; I especially want to encourage more mainstream audiences to engage with the history of feminist ideas, especially as they relate to film,” says Cambier.

To introduce more people to female-animated films, Cambier holds screenings of the films she researches, like Stand with Standing Rock by Martha Colburn and Asparagus by Suzan Pitt. Viewers always enjoy the films, and are often shocked by the dark and political content of them. “I have had the good fortune to screen groups of my case-study films for audiences and the response is always surprising—and very positive,” says Cambier.

By bringing awareness, and thus justice, to these films, Cambier hopes that viewers will discover a plethora of animation that they didn’t know existed. “My goal is to get more people watching these films and knowing the names of more women animators,” she says. To Cambier, this is more than just a dissertation—it’s giving female animators and their messages the recognition they deserve.

This story was written by an undergraduate student in Backpack. Meet the team.