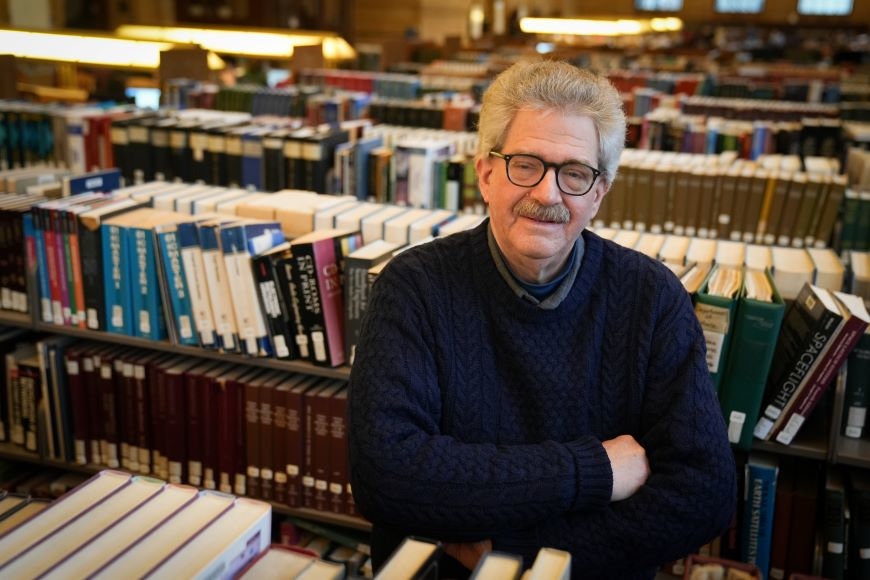

For the Love of Learning

James Parente was in 10th grade, in suburban Philadelphia, when he developed his first curricula—a kind of intellectual exercise. If he were teaching a course on, say, ancient history, what books would he assign? Herodotus? Thucydides? Plutarch?

Books were beginning to accumulate in his house and in his mind. He kept a ring binder with a long list of novels to read by Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Dickens, Conrad, Dreiser, and Thomas Mann. In high school, he studied ancient Greek, German, and Russian—in addition to the Latin he acquired through his Catholic school education—so he could read even more.

“I was very bookish,” Parente says, “very interested in learning.” His mother introduced him to opera (“A decision she lived to regret,” he jokes) and he became drawn to drama—the hard stuff, of course: Shakespeare, German opera, Norwegian plays. By the time he went to Haverford College, a few miles from home, he knew exactly what he wanted to be: a high school teacher.

Parente, who retires this January after three decades in the College of Liberal Arts, has been many things: professor of German, Scandinavian, and Dutch; associate dean for faculty and research; dean of CLA, director of graduate and undergraduate studies, director of the Center for German and European Studies. He never did teach high school.

“After two semesters at Haverford, I thought, ‘I want to be one of these professors,’” he says. “‘They have a lot of cool books on their shelves.’” He ended up specializing in the Renaissance and early modern period, where many of his interests intersect. This meant more languages to learn: Italian, French, and then—as his studies drifted northward—Dutch, Old Icelandic, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish. “I’ve just been accruing the languages I need based on my interests,” he says.

Parente settled intellectually in premodern Germany, the story goes, the first time he saw a map of the Holy Roman Empire, with its hundreds of little principalities. It looked complicated—just what he wanted. “Real understanding of this period demands intense study,” says history professor Howard Louthan, the director of the Center for Austrian Studies. “You have to get these languages down, and then if you’re working with 17th-century German material in the archives you have to learn to read the old scripts, which are difficult to pick up. At the end of the day, you have to work really, really hard.”

After earning his PhD at Yale and teaching for several years at Princeton, Parente took a job in the German department at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1986. He enjoyed the cold, dark winters—the better to stay in and read—but found his thoughts drifting to an even colder, darker place: “Look at those lucky people in Minnesota.” When the University of Minnesota hired his wife, Arlene Teraoka, a now-retired scholar of German literature, Parente was happy to follow.

The Interdisciplinary Dean

It was an adjustment, dealing with frozen pipes and dead car batteries. Parente’s position at the University, too, took some ironing out. Hired in 1990 as a visiting associate professor of German, it wasn’t until 1993 that he was brought on as a full professor. By 1998, he was the chair of what is now the Department of German, Nordic, Slavic & Dutch.

Two years later, he was recruited to be the associate dean for faculty and research. It was stimulating work, figuring out how to build up departments and research capacities. Parente helped conduct some 40 to 50 faculty searches a year, many outside his expertise, and he would read up on the candidates and their work—learn their language, as it were.

“Candidates would be astounded at the level of detail he had gleaned,” says Evelyn Davidheiser, director of the Institute for Global Studies. Within a few years, the number of CLA faculty had swelled, likely to its highest-ever level.

Becoming dean of CLA in 2008, after a year as interim dean, felt like the culmination of lifelong interests. And then the economy collapsed. Parente dove into the College’s myriad departments to help in the hunt for resources. “I was really quite fascinated by what was going on in each of the fields,” he says. “How would we advise the students? Where would we get the money for this?"

There were hard choices, hard feelings. Professor of Sociology and Ohanessian Chair Joachim Savelsberg says Parente was inclusive, effective, and fair. “Within CLA are all these very diverse branches, from music to dance to literature to social sciences,” Savelsberg says. “Yet he understood what people were talking about and was receptive to their suggestions and ideas.”

Parente represented his field as the rare dean with a literary background, and he proudly cut the ribbon on Folwell Hall’s renovation in 2011. (Folwell houses four departments focused on languages, literatures, and cultures from around the world.) He stayed in touch with former graduate students as they progressed in their careers, keeping an eye on job openings, offering suggestions for their next steps. “There aren’t many scholars left in premodern German studies,” he says. “I want them all to be successful.”

But he especially enjoyed bringing people from different disciplines together, and watching the intellectual sparks fly. “Others in his field might stick to their disciplinary boundaries, focusing on literary questions,” Louthan says. “Jim’s not like that all…he’s so widely read, so interested in theater and art and political developments.”

“He thinks big, not just beyond disciplines but beyond colleges,” Savelsberg says, recalling when Parente asked him to help lead a human-rights initiative with CLA, the law school, and the Humphrey School of Public Affairs. It resulted in annual funding for human rights research and a master’s program in human rights—the first in the country jointly run by a liberal arts college and a school of public affairs.

In 2013, Parente decided to return to the faculty. But after more than a decade away, and with the perspective this afforded him, his work took on new dimensions.

Challenging Expectations

In 2014, Parente became director of the Center for German and European Studies, which he had helped create in the late 1990s. Like most academic centers in CLA, it is an “interdisciplinary space,” Davidheiser says, drawing faculty not just from CLA but also other colleges at the University and neighboring institutions. “Oftentimes they’re introduced to colleagues they didn’t know existed.”

Supported administratively by the Institute for Global Studies, the center is part of an international network of scholars. Parente championed exchange programs for American students and faculty to go to Germany, and vice versa. He helped organize transatlantic forums on violence and other big topics. “It mattered to him that CLA is the international college at the University,” Davidheiser says, “and he made sure that the role we play in this work was front and center.”

Professor Henning Schroeder, who will take over as director of the center in January 2023, calls Parente “a true Renaissance man” in his instinctive bridging of boundaries and borders, “a true searcher in the tradition of the humanists.” Indeed, Parente recently helped bring Schroeder, who had been teaching pharmacology, into his own department to teach a course on contemporary Germany, recognizing the German native’s interest.

Parente’s own research has taken on a broader focus as well. In recent years, he has examined the ways that Europeans imagined their past in literature, shaping national histories. He has explored the idea of Europe itself—how this larger identity developed in historical writing, subsuming local interests. And he has traced the flow of literature, particularly Dutch and German, across boundaries, revealing how texts and ideas circulated throughout Europe.

Much of his recent work has centered around the Dutch Golden Age of the 1600s, when a newly prosperous Netherlands spurred a cultural flourishing. Only recently has the source of that prosperity—the slave trade, colonization—been widely acknowledged, complicating the narrative. It’s the kind of reckoning that Parente relished discussing with students.

“I liked to challenge their expectations of something they think they know well,” he says. “We could talk about big, controversial subjects—the Reformation and the papacy—and it’d be mind-blowing to students coming out of high school. Providing this kind of neutral space to talk about difficult topics is so important—increasingly so, given the polarization in our society.”

If there is always more to learn, as new perspectives emerge, there is also more to unlearn. “When we’d interpret a literary text,” Parente says, “and everyone would agree it’s great, I’d ask, ‘How would you read this if you were a Marxist or a feminist scholar? How would Trump read this?’ There has to be a willingness to hear the other side. We need to find more common ground.”

This openness, which has driven so much of Parente’s work, is one reason he’s not quite ready to be done—even in retirement. He will still research, still publish, still pursue his interests into unknown territories. “In my mind, I think, ‘don’t overcommit,” he says. But his curiosity has always had a mind of its own.