The March on Washington for Jobs & Freedom: A History Revealed

Historian and professor William P. Jones wrote the book, literally, on the March on Washington for Jobs & Freedom. And as CLA prepares to commemorate the 60th anniversary of this emblematic event, Jones’ research proves that remembering history also means revealing it. From the profound role of Black women in the movement to the intentional ambiguity of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech, Jones shares eight facts about the march that your history books might have missed.

The march was initially about jobs; freedom came later

There’s a narrative that the civil rights movement started out addressing issues related to racial equality, desegregation, and voting rights, and that as the movement evolved, it became more expansive both in terms of region and issues.

What I found through my research was that, from the very beginning, it was a national movement. The people who started what would become the march were northern activists from New York, Chicago, Detroit. And the initial focus was actually the demand for jobs before it evolved to include issues we often see as the primary issues for civil rights: integration and voting rights.

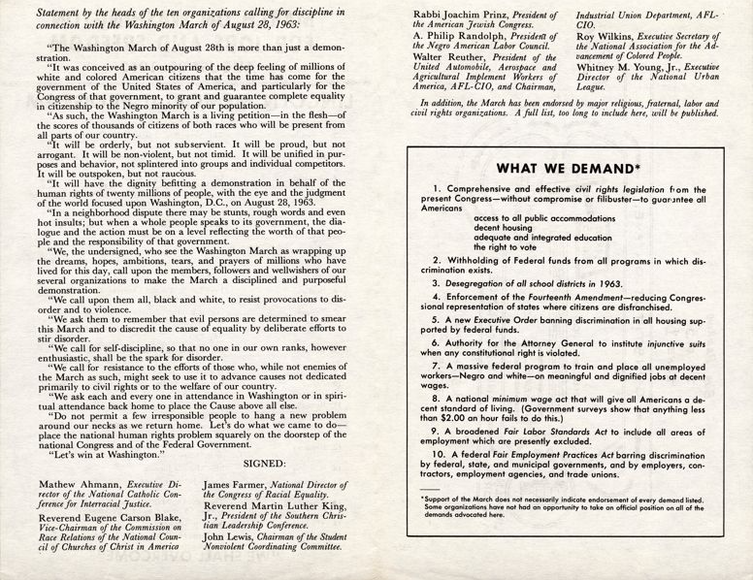

Organizers wanted to make the point that none of these things could really be achieved in isolation; it was critical that racial and economic justice be fought together.

Its history dates back to the Great Depression

The immediate call for the march came in early 1941, but touched back into the 1920s–30s. The US wasn’t in the Second World War yet but President Franklin D. Roosevelt had called on the country to become an “arsenal of democracy.” In other words, we’re not going to enter the war but we’re going to produce the weapons and equipment to supply our allies.

This became a massive federal investment—turning auto plants into airplane manufacturers and ramping up production of ships and tanks. As a result, it dragged the US out of the Great Depression and the country went from high unemployment to low unemployment rates.

African Americans, though, were almost entirely shut out of these jobs. Employers refused to hire Black workers and many unions excluded them from membership. So, Black workers were still in the Depression while white workers were emerging from it. The president was saying “we’re going to fight for democracy;” Black workers were saying “it’s not democracy if we can’t participate.

A woman is credited for having suggested the march

There was a draft, African American workers started to resist it, and there were protests in cities all across the country. A. Phillip Randolph, a prominent civil rights and union leader at the time, led a meeting to talk about what to do, and an anonymous woman shouted, “let’s march on Washington!” Everyone thought that was a good idea.

Randolph’s union, composed of mostly African American members, mobilized during the spring of 1941 and later that summer, it was estimated that 100,000 people were going to participate. The organizers had two demands: integrate the armed forces and prohibit employment discrimination.

The original 1941 march was canceled just a week beforehand

Initially, the president refused to meet with organizers and said something to the effect of “I’m not going to negotiate with a gun to my head,” but at the last minute, just a week before the march was supposed to take place, he conceded. He agreed to meet one of their demands and issued an executive order banning discrimination.

This was a huge victory at the time, some even compared it to the Emancipation Proclamation, but the provision itself was pretty weak. The president set up what was called the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC), gave it little money and offered little enforcement. It was also a war-time emergency order so when the war was over, it expired.

The march was called off with the acknowledgement that, if things got really bad, they could always march again.

Minnesotan Anna Arnold Hedgeman advocated for a broader slogan

It was really in the 1960s when the level of frustration rose to a new level. There had been a series of intense conflicts over segregation and it seemed like little progress was being made. The economic situation for African Americans was beginning to decline again, and unemployment rates were starting to tick up, particularly in northern cities.

A. Phillip Randolph said “these are the long-term effects of discrimination—if we don’t address this, it’s going to get worse.” We need to set up this fight for fair employment and qualifications not based on race.

When they said they were going to march for jobs, the person who said we need to broaden this message was Anna Arnold Hedgeman, a civil rights leader who had grown up in Anoka and attended Hamline University in St. Paul. She had led a campaign for a permanent FEPC and established an office in Washington to lobby for the law. She had said” this is important, we should march for jobs, but we should also march for voting rights and integration.” She proposed the slogan “For Jobs and Freedom.”

Her work really helped to reignite a feminist movement. Particularly for Black women, there had always been this question about how much do you push on fighting for gender equality in a movement that’s fighting for racial equality. It led Black women to take a much stronger position on fighting for gender equality after the march.

At the time, it was the largest march in US history

In writing the book, I wanted to show how hard it was to actually build this event. It took 20 years to form the kinds of networks and relationships that came from getting people to go. It was important for me to understand how that happened and the meticulous planning that went into bringing 200,000 people to Washington.

Through my research, I discovered records of union activists. Union leaders had these built-in networks in cities across the country, which meant they could say to their members, “this is really important, let’s all go,” and charter buses, trains, or—in some cases—planes, that would actually move people to Washington. It was a weekday so people took off work that day, but some unions actually negotiated with employers to give them the day off.

When we think of it today, we think of it as this event where people just showed up, but it’s vital to remember how they got there, why they got there, and what was at stake.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech was intentionally vague

MLK has been centered, you frequently hear the event referred to as “MLK’s March on Washington.” And MLK was a really important figure at that march, his speech was by far the best, but I think the way in which we think of it as the sum of the march overlooks a number of important things.

He was just one leader and, at the time, wasn’t seen as the most important leader. It’s important to recognize how many people’s expertise and experience went into building this—people like A. Phillip Randolph, a socialist union leader from a much different generation, people like Bayard Rustin, who was the technical strategic organizer of the march. It wasn’t just MLK saying “meet me at the Lincoln Memorial.”

We also know his speech very well but we have to remember that his was the last of ten major speeches. His charge was to rile people up and send them home eager to keep fighting. So by the time he got on stage, he didn’t have to say what the goals of the march were; they had already been said over and over again in the other nine speeches.

His speech is often taken as, “this is what the whole civil rights movement was about,” but it was purposefully vague: “This is our vision of a world in which everyone is treated equally”’ without specific mention of the march’s actual demands.

Civil Rights legislation was expanded to include gender equality

One of the most important outcomes of the march was to build support for a federal anti-discrimination law (which becomes Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act). President John F. Kennedy had opposed a fair-employment provision, but after his assassination in November 1963, it was added under President Lyndon Johnson. That was a really important addition and perhaps the central goal of the march.

That law was changed in the process of passing, too. The same Black women who had been excluded from official march leadership advocated that the law be expanded to also prohibit gender discrimination; initially it was going to prohibit employment discrimination based on race and national origin.

Now, that’s viewed as one of the most important parts of the law. The fact that it prohibits gender discrimination as well as race discrimination dramatically increased its impact.

Revisit the March on Washington

Access uninterrupted coverage of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom via OpenVault, the only complete audio coverage of the broadcast in existence.