Getting on the Same Page About Book Bans

Earlier this year, Minnesota adopted a new law “banning” book bans. This Banned Books Week, we want to consider what that might mean for Minnesotans—and how book bans affect and reflect our larger society.

Associate Professor Lianna Farber teaches the English department’s popular class on banned books (ENGL 1004) twice this year. We asked her some questions about this nuanced issue and the power of books.

First, what is a book ban? What isn’t one?

It’s a good question because there isn’t a single definition. Most people would say a state law that prohibits public libraries or schools from shelving certain books is a ban. And many would say the same about school boards that remove particular books from their districts. But what about a library that places controversial material aside, where you can borrow it if you ask for it? Or a school that removes a book from a multi-age general library but lets teachers of older students keep and teach the book? Or, conversely, a school that removes a book from the official curriculum because of its content but leaves it in the library? And what about a book that is temporarily removed from libraries or classrooms when a school board considers a challenge, but is then returned? And does your answer to those questions change depending on whether the book is openly supportive of or hostile to same-sex relationships, political activism, or any given person or period of history?

Some people consider any restriction at all a “ban,” while others believe that none of the situations I described counts as long as a book can be legally sold, and is therefore technically available.

Who is doing this book banning? Where are the books being banned from?

Let’s start with the “where,” because that’s more straightforward. Books are most often banned from schools—this can be school libraries, classrooms, or both. Increasingly they are banned from public libraries. There are some states where lawmakers and other officials are trying to regulate how books are sold, by attempting to institute mandatory rating systems, for example.

As for the “who,” it depends on whether you’re thinking procedurally or about larger forces. In a transactional sense, books are and have been banned by state legislatures and local school boards, as well as the various bodies of municipal and county governments that oversee public libraries. In terms of who drives those bodies to act, some people say that in the past, it was individual parents who objected to a book found in a child’s backpack, whereas now it’s large political action groups. That’s not entirely true—groups successfully circulating lists of books that they urge others to ban go back more than 50 years—but the internet certainly makes it easier to disseminate lists and information, and book bans have become deeply politicized.

Today, the answer to the larger “who” is often groups of adults acting together. Some of them may be only cynically interested in using this issue for larger political reasons, while others are genuinely concerned about what the books teach and say. Some people fall into both camps. And there are still places for an individual parent to become upset and instigate a challenge. I think it’s also important to note that even though this issue has been seized by many on the political right, people on the political left also have supported and do support bans, broadly understood, even though there is little agreement between the two parties about which books should or should not be included.

Which parts of your class most challenge your students as readers and citizens?

It’s often challenging to realize that although book bans can be political, they are not only political, and the issue is difficult rather than easy. Our polarizing culture makes it simple, even almost necessary, to take a side. And although that is, of course, possible, and perhaps convenient, I don’t think it's terribly interesting. The history of banning books is very long—Plato advocated book bans in The Republic. He took that position because he thought that books were incredibly powerful and were therefore dangerous. Christine de Pizan, at the turn of the fifteenth century, wrote about books’ ability to change the way people think about themselves.

This belief in the power of books is often shared both by the people who most fervently want to remove books from places where they can cause harm and also by those who most fervently oppose book bans because of books’ potential to do good. In other words, both sides impart this tremendous agency to books. Do books hold that kind of power? If so, how and why do they wield it? And if they do, is it our responsibility to regulate either books themselves or who has access to them? I mean, in this day and age when we all have much more than a library’s worth of information constantly accessible from a device in our pockets, it can seem almost quaint to worry about books in libraries. Is worrying about this issue the modern equivalent of debating carriage safety regulations after automobiles ruled the road? I don’t think these are straightforward questions.

In my class, we read books that make people uncomfortable—books that use racial slurs and racist stereotypes, or see the world through the eyes of a pedophile, or advocate violence. We also read books that speak to my students’ idealism, and some that they think are innocuous, or even banal. After all, a book isn’t good just because it’s banned, and some don’t appear controversial or consequential to most of my students. The challenge is, if you believe that books do nothing, why would you worry about what’s available or not available? Neither access nor bans should be of much concern. And if you believe that they do something, perhaps many things, how do you formulate a position that can apply equally to all books, rather than falling back on “books I find helpful should be allowed but books I think are harmful should be banned”? That kind of juvenile thinking doesn’t make good law or policy, however popular it might be.

What do you think the new state law "banning" book bans will mean for Minnesotans?

I think it could help librarians feel safer, and I’m always in favor of that. But it isn’t really the “ban on book bans” that advocates promise and opponents fear. Even though it prohibits book banning, the limitations include, and I’m going to quote here, “legitimate pedagogical concerns, including but not limited to the appropriateness of potentially sensitive topics for the library's intended audience.” And that question of what’s “appropriate” is, of course, at the heart of the dispute, which in turn means that most books can still be challenged. Is a book “appropriate” for a school or public library if it includes a romantic kiss? What if the kiss is between two boys? What if it’s between a middle-aged man and a prepubescent girl? The law often invokes a “community standard” about what’s acceptable in cases like this, but, of course, these questions only become urgent when the community doesn’t agree on a standard.

Which "banned books" do you wish more people would read and why?

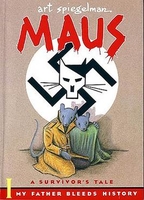

It’s hard to go wrong with anything Toni Morrison has written. Beloved is currently near the top of most lists of banned books, and, personally, I’d say that anyone who hasn’t read it, should, and anyone who has might want to re-read it. Art Spiegelman’s Maus is stunning. But mainly, for me, it’s more about how you read. I’m in favor of thinking consciously about whether a book changes your mind, whether it moves you, entertains you, makes you angry, or gives you ideas. And if it does give you ideas or change your mind, by what means does it do that, and to what end? In the way that you think the author intended? Can it make you believe or understand something, whether a feeling or a person or an idea or an emotion, that you otherwise wouldn’t have? I think it’s hard to have a sensible discussion about banned books without thinking more about the power and limitations of books in general.

Read and learn with us

Registration for ENGL 1004: Banned Books in spring ‘25 opens on November 12 for enrolled students and December 6 for non-degree-seeking students.