Making it in Minnesota

“Minnesota? Are you nuts?”

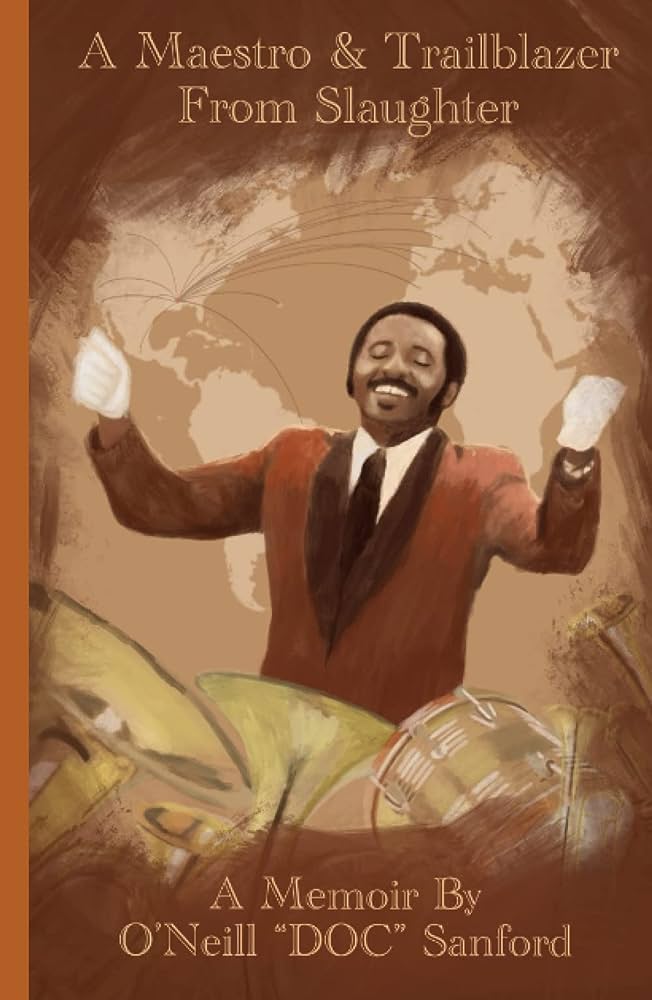

“Doc” O’Neill Sanford recalls the coffee date that changed his life.

It was 1976. The marching band director position had been posted at the University of Minnesota and one of his colleagues was encouraging him to apply. “Somebody has to open up this field for African Americans,” his colleague had argued. “Maybe it’s you.”

But Sanford had already experienced a whirlwind of milestones, graduating from Southern University, starting a family, and landing a position as director of bands at Virginia State University. Not to mention, Minnesota was cold—in more ways than one.

“Are you nuts?” Sanford remembers saying. “No way am I going to Minnesota in the cold weather where 99% of the students and faculty are white.”

The two finished their coffee and the matter was seemingly dropped until a few weeks later when Sanford received a letter from Minnesota, thanking him for applying and asking for additional materials.

“My friend had sneaked around and sent my resume to the University,” he laughs. “He said, ‘I really think you could do this job, what do you have to lose? Send your stuff up there!’”

So Sanford conceded. He submitted his materials and was named a finalist before eventually being offered the position. Sanford was in disbelief, but thoughtfully considered his options: stay in Virginia and “wade in the water” or move to Minnesota and see if he could “go out into the ocean.”

Up until that point, there had never been an African American marching band director in the Big 10—was he prepared for the exciting, yet terrifying opportunity to be the first?

In the end, he says, “I made the decision to see if I could swim.”

“Hey, I want to play that!”

Ironically, Sanford’s journey into music education began with a rejection.

He had failed his rhythm test as a high school freshman and wasn’t permitted to join the band. Although he had never played the trombone, his instrument of choice, he spent his childhood falling in love with its sound.

“Every summer, my mom would put us on the bus to visit my great aunt in New Orleans,” he shares. “I had five sisters and was the only boy, so when my aunt would take my sisters shopping, I’d get dropped off at Louis Armstrong Park. That’s when I first became familiar with the trombone.”

Sanford looked forward to these visits every year, watching the brass bands perform throughout the park and especially gravitating towards the powerful sound of the trombone. Soon, he came to the realization, “Hey, I want to play that!”

But back home, in a rural community outside Baton Rouge, Sanford had flunked his rhythm test and made the decision to pivot to football. (Then, when he experienced his first run-in with a 230-pound lineman, Sanford promptly pivoted out of football.)

His luck would change the following year. A new director arrived and agreed to let him join as long as his parents could buy him a trombone.

“My dad looked at me and asked, ‘son, do you really want to do this?’ And I knew that once I committed, I couldn’t quit. So I said, ‘yes!’ and we went that same night to buy a trombone.”

One trip to Sears Roebuck and $75 later, Sanford finally had his beloved instrument and, most importantly, permission to join the band. By the end of his sophomore year, he had also racked up some impressive accolades, being named president of the band association and its most accomplished musician.

Sanford went on to study music education at Southern University in Baton Rouge. He served as the director of bands at Ferriday High School in Louisiana and at Mississippi Valley State University before he was hired at Virginia State, a historically Black college and university (HBCU).

“Southern University equipped me with the necessary tools and basic fundamentals of music to survive in the profession. My direction and success were motivated by my professional mentors, high school and college band directors, and two of my best friends and fellow trombone players in college, Mr. Paul I. Adams and Moses Hall.”

O'Neill Sanford

His biggest adventure was just around the corner.

“When you played music, it didn’t come out Black or white, it just came out as music”

After he accepted the position in Minnesota, Sanford remembers feeling as if the whole world was watching. And disapproving.

"The eyes and ears of the instrumental music education world were watching, listening and scrutinizing the success of my work. It was terrifying.”

“Some Black directors were upset because I was leaving the HBCU schools. They kind of thought, you deserted us, we need you here,” he shares. “And then, I knew there were other people who weren’t happy that an African American had gotten the job in Minnesota. The eyes and ears of the instrumental music education world were watching, listening and scrutinizing the success of my work. It was terrifying.”

The move also marked an unsettling first—it was the first time in Sanford’s life he had gone against his father’s wishes. He had been raised to respect his elders’ advice, but when his dad told him, “I think you’re making a mistake,” Sanford remained steadfast in his decision.

“I had to do it because I had to find out if I could do it,” he says. “I couldn’t afford to walk away from the opportunity.”

Thankfully, Sanford’s big risk reaped big rewards.

He describes the University of Minnesota as the place where his feet became planted on the ground; where he was exposed to a comprehensive, instrumental music program—one of the best in the country—that bolstered his skills as a young director. Along the way, he discovered his own untapped talents in arranging and writing music.

I developed more in Minneapolis than in any other place I have been. It was one of the best decisions I ever made.

O'Neill Sanford

Sanford acknowledges his time in Minnesota had its challenges, too. “It was 1976 and crazy stuff was going on all over the country. I did run into a few racial issues, but also learned that music can calm the wildest beast. When you played music, it didn’t come out Black or white, it just came out as music.”

During his nine years with the Pride of Minnesota, Sanford’s students challenged him in meaningful ways. His faculty peers Dr. Frank Bencriscutto, Dr. Lloyd Ultan, and Dr. Austin Caswell mentored and guided him through the process of securing tenure. He befriended high school band directors across the state. And in time, he even won over his toughest critic.

“My dad visited and had the chance to interact with the whole staff. I called him on the phone when he got home and he said, ‘Son, I was wrong. Those are some great people and I felt their love, their respect. I gave you some bad advice and I’m proud of you.’”

“A bona fide nutball for music”

Sanford jokes that he never should have left Minnesota, but another extraordinary opportunity was headed his way—rebuilding the band program at the University of Pittsburgh (and discovering polka music for the first time!).

Serendipitously, he would also find his way back to the HBCU community. Sanford served as director of bands at Norfolk State University and Jackson State University, experiences that would leave a lasting impression.

“After going back there, I discovered that many HBCU programs had not advanced beyond what I graduated from 40 years prior. My goal was to make sure that every student who came out of that university did not lack any experiences and to make sure they were exposed to a comprehensive program before they left.”

Sanford founded the HBCU National Band & Orchestra Directors' Consortium to “collaborate & develop strategic plans for success in instrumental music.” The organization has held in-person conventions in Atlanta nearly every year for the past two decades, bringing together directors and students from historically Black colleges, universities, and high schools. He considers it one of his proudest achievements.

And after three retirements and 55 years in music education, Sanford still wakes up with the desire to create, sometimes in the middle of the night.

“I’ll wake up at two in the morning with a certain sound, a certain musical chord in my head, and I’ll have to get out of bed and play it on the piano,” he laughs. “My wife describes me as a bona fide nutball for music.”

Commemorating the March on Washington

The Pride of Minnesota welcomed back Professor Emeritus O’Neill Sanford on August 31, 2023 for a special Motown-themed halftime performance. This show was presented as part of the College of Liberal Arts’ Dream Initiative, celebrating the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington. Read more about Sanford's homecoming in "A Marching Band Legacy Returns to the Field."