Sound In Art

“Sound Art orients us to listening as a mode of creating and experiencing art. It can transport us in time and space while introducing new perspectives, sensations, and ways of knowing," says Diane Willow, a professor and the director of graduate studies at the Department of Art.

In her course, Art and Sound, students are introduced to an eclectic range of contemporary artists who work with sound as their artistic medium; each person is encouraged to expand their engagement with art to center the sonic. “[It’s] like someone removed a veil and… wow, there’s this whole other color in the rainbow I never saw,” says Camden Stevens, a junior Art BFA and Product Design minor in the class.

Organized with a sequence of three themes—Site Sound, Embodied Sound, and Independent Projects—students in the Art and Sound course are guided through the process of deep listening, inspired by the work of composer Pauline Oliveros, as they develop their personal relationship with sound as an artistic medium. The Site Sound project invites students to approach their everyday environments anew by tuning into every sound that they can perceive.

Through this practice, they listen, record audio, imagine, and create new sites of sonic experience. Whether it's the ambient sounds of a coffee shop, the flurry of morning birds, or the receding sound of pedestrians walking down Pleasant Avenue, students focus on what they hear rather than what they see and realize that there is a whole new layer to be discovered in that sound. In Embodied Sound, the focus is on the physicality of sound as a tangible medium that may center material or sculptural approaches, performance, installation, or the ways that their own bodies produce, respond to, or experience sound.

With a uniquely innovative format, each student's sound artwork conveys their particular aesthetic, social, cultural, ecological, or phenomenological relationship with sound.

The Plant Wave

In the Spring 2023 Art and Sound course, students were introduced to a technology called Plant Wave that translates biodata from plants into sound. Inspired by the electrical energy in biological bodies and her own recurring engagement with plants and plankton in her artistry, Willow guided students in creating art pieces inspired by plants, the electrical energy in living organisms, and possible relationships between the sonic and the tactile.

In these biologically inspired sounds, students explored sonic relationships that interested them while conceptualizing unique pieces that they shared with the class. Undergraduate students Andy Hanson, Leah Hallett, and Andje Post made a participatory sound installation inspired by the Plant Wave technology, as well as their interests and expertise in architecture, fabrication, and environmental science.

Using a gridded, vertical array of metal rods, in the spirit of Harry Bertoia’s sculptures, they created a semblance of artificial plant forms that acted as a sonic instrument and was responsive to human touch. Like how a breeze might move an organic flower, every human touch of the metal flowers activates a different sound, creating a garden of tones that generates a different composition by each person or group of people who interact with it.

Heartbeats and the Soul

Other students worked independently or collaboratively, with many focusing on intimate personal experiences. For their Embodied Sound Projects, Salma Ibrahim and Kali Barry each shared their discoveries of self and soul through sound.

Ibrahim is a Junior Art major, and her project focused on the stories of heartbeats. Inspired by the term Embodied, she chose to look within bodies to see what these sounds reveal. By inviting each student to place a digital stethoscope to their chests, she amplified and presented in surround sound, each person's heart beat—how fast, how strong—a personal, ephemeral, and rhythmic portrait. Wondering why each heart beats differently in that moment, in heartbeats, Ibrahim found a window into a person's soul. “Listening to someone's heartbeat is kind of intimate in a way… you get to learn more about the person and their story,” says Ibrahim.

Her sound artwork revealed that some students' hearts beat faster while some were slower. Some had a quieter heartbeat while others were loud. Ibrahim’s own heart beat more rapidly than anyone else's, revealing her anxiety as she took an artistic risk to realize her sonic concept. “The sound of a heartbeat is art because it expresses our emotions… I feel like everyone should have a chance to listen to their own heartbeat.”

Chalk and Childhood

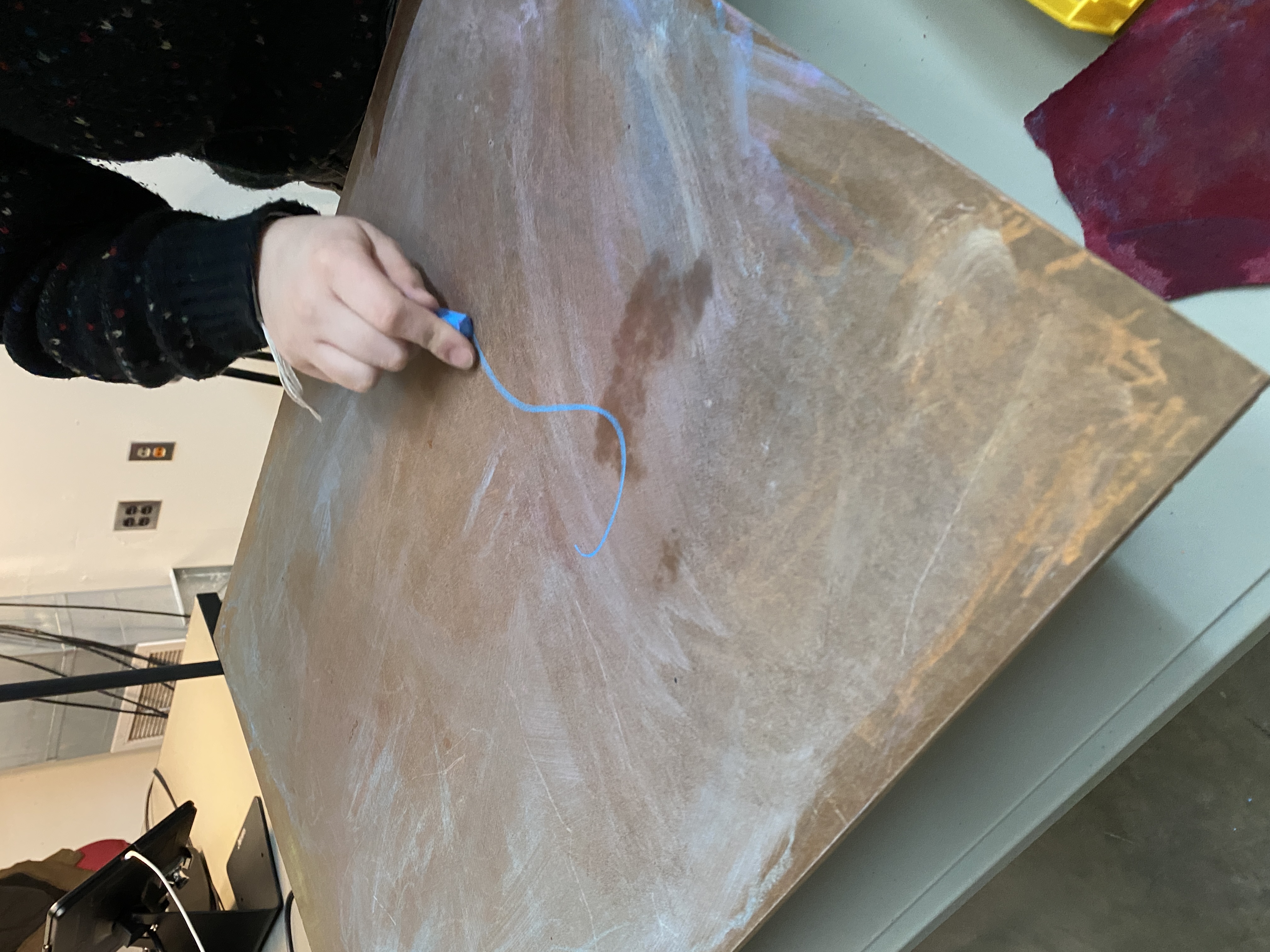

Barry, a junior individualized studies major with a Filmmaking

emphasis, chose to focus her Embodied Sound Project on the sounds we create when we interact with the world. Inspired by a childhood memory of drawing chalk on the sidewalk, she invited students to participate in her performed presentation, using an amplified board, chalk, and an invitation to draw freely. See (and hear) for yourself in this video clip Art + Sound: Embodied Sound.

As they drew, the sounds transformed the room. She asked the class to close their eyes and imagine how the sounds were created and who was drawing them. Some tapped, some scraped, some circled. Some drew with more pressure or less. Each sound revealed more and more about how a person was drawing, the energy of their gestures, and how, in that moment, they were drawn to interact with chalk and drawing as a creative medium, and how, in this process, they resurface such an iconic remnant of childhood.

Through this artistic medium, Barry invited people to open themselves to childhood memories and to see and hear what parts of themselves were unveiled. “When I drew on the sidewalk it was never the same,” says Barry. “I wanted to recreate memories of when my friends and I would work hard on a chalk piece. Chalk is fairly memorable, it has a very distinct texture and stains the skin, kind of like how memories can be very distinct and can become ingrained into our minds.” When those memories are opened up again, they can take over and bring back the unique child in every person.

Sounds into Art

The Art and Sound course introduces a new medium through which students can explore their relationship with art, experiment with new modes of creative inquiry, and reveal the power of all things sonic. Through sound, they learn to see art, bodies, and the world in a different form.

“My goal is to encourage each student to develop or deepen their relationship with sound and sound art,” says Willow; “ to invite people to participate in the process of creating sonic experiences that reflect their individual and collaborative sensibilities while also sparking a sense of artistic connection with themselves and one another.” Through her annual Spring Semester class, offered as ARTS 3230 and ARTS 5230, students at the University of Minnesota continue to reveal the power of sound as an artistic medium.

By Zayna Amanat

This story was written by an undergraduate student in CLA.