Black Abstraction in the Midwest: Q&A with alumnus, artist, and curator Gregory J. Rose

Change is God-Take Root Among the Stars: Black Abstraction in the Midwest is a group exhibition of 17 artists, including several UMN MFAs, at Soo Visual Arts Center in Minneapolis. The impressive roster of talent includes Lela Pierce (MFA '22), Stephanie Lindquist (MFA '22), Marcus Rothering (MFA '25), and incoming Lecturer Christopher E. Harrison, among many other exceptional artists. The curator, Gregory J. Rose, also has ties to the Department of Art, having earned his MFA here in 2004.

The exhibition, according to SooVAC, "seeks to discover what shifts are occurring within the canon of abstraction through the lens of the Black experience." On view are works in painting, ceramics, textile, performance, assemblage, and mixed media installation, encompassing a variety of approaches to contemporary abstraction.

Ahead of an artist panel discussion and closing reception this Saturday, July 30, 5-8pm, we caught up with Rose to discuss the exhibition and the questions it raises.

Russ White: Abstraction, by definition, has an antecedent – an inspiration, a starting point from which to explore – and several of the works in this show use the body as that starting point. There is Sarah White’s projected performance moving her body in and out of bondage, Monica J. Brown’s colorful extrapolation on two people embracing, and the hint of hidden faces in Ta-coumba Aiken’s tondos, among others. How did the body, particularly the Black body and its history in figurative art, fit into your approach in conceptualizing and curating this exhibition?

Gregory J. Rose: It's interesting that you asked that question, Russ. The way I went about this exhibition was that I don’t feel that I am the leading authority or academic to define "Black Abstraction/ Abstraction" so to speak. But working in the history and context of "Black Abstraction/ Abstraction," I feel that my vision and the exhibition has shed light onto this! The fact is, "Black Abstraction/Abstraction" is not fixed, nor are its inspirations/subjects/concepts/philosophies/materials(media) or processes.

From the beginning I have been and still keep engaged in the conversation that this exploration of "who my peers are" has arrived at. Which brings me to the body. The vessel we use to travel, we move our feet, use our eyes and ears, our mouths for taste and hands to make, work, and survive. In fact, we can argue that we use all of our five senses to survive – as we search for ways to sustain and thrive. Our bodies, black bodies, female black bodies, children, and men historically began as just an innocent life. Yet, historically we know in the order above our bodies have been commodified, industrialized, focused on scientific, spiritual, and philosophical investigations, interrogations, and elimination.

Rather than curate this exhibition in the ways of our Western, White, Colonial, and hyper masculine culture, I decided that I wanted all the artists to come "Home" – to bring their bodies, minds, and creative attributes here to Minneapolis, the starting point of what I would say is Baldwin’s "Fire Next Time," the killing of George Floyd and the start of a national movement with BLM leading a lot of the way – the uprisings lead by BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, those who we at time say for lack of better words live on the fringe/test the water/challenge the status quo, and specifically ARTISTS who are from the main groups listed above along with our allies.

Meeting with the artists and again, not curating under the conditions of the historical academic and western art world canon, I wanted the artists to take the - Risk!!!! To make the work and talk about those inspirations that they have been/we have been historically unable, disallowed, kept from, nor supported in. What came of most of these phone calls, Zoom meetings, and studio visits was this main thread. Most if not all of us started our journey in the arts in some way talking visually about and clearly representing – for reasons of survival, protest, activism, education, spiritual, or religious reasons, and searching for one’s identity and home – the black body.

I myself started as a self portrait artist – starting off with the history of African American limners, moving to Alan Locke, W.E.B Dubois, and the Harlem Renaissance, and moving from inspirations like William H. Johnson to Robert Duncanson and the Ohio school painters, finding black abstract expressionism, and loving Basquiat by the time I was graduating my undergrad in 2000 at Penn State University. By the time I applied to the U of M, my stepmother, who was a white woman and who raised me from when I was the age of two, died during my last year of undergrad from complications from scleroderma. So, again to your question: when I made work after being in mourning for about half of my last semester in undergrad, all my color left, all the representation or literal representation of the black body or the inspirations and ideas behind my marks, images, textures, colors – everything went black. My work began to form around a larger and at times a more universal way to talk about "Blackness" in all its glory, definitions, contradictions, and possibilities.

I feel these artists all share similar shifts in many different contexts and from different origins. But the first story we all began with was about and from our bodies, their identities, and the possibilities that come from us as black vessels. The limited options, the ways in which "others'' are able to dismiss what we bring to the audience as just "black" issue(s) or just "Black" culture, is reconfigured and the conversation becomes more layered, complex, nuanced, and at times universal in the space and world of abstraction. The body, mind, spirit , philosophies, and ideas around black bodies and where it meets black abstraction – well yes, for me, they should and can be attached to the body. How much of this is literally seen, talked about, or found evident in the processes and materials? That’s just one of the conversations and/or spaces this exhibition starts to fill.

Are there other starting points that the artists in your show used that you would like to highlight?

Yes. Naima Lowe – Black/Queer/ Feminism/Abolition/ storytelling and quilting – her didactic of how we all can raise our own flags of identity is so powerful.

Amirah Cunningham, Bruce Armstrong, and Alexandra Beaumont, I would say are working form a new Black minimalism.

Marcus Rothering – tension between African American object and artifact.

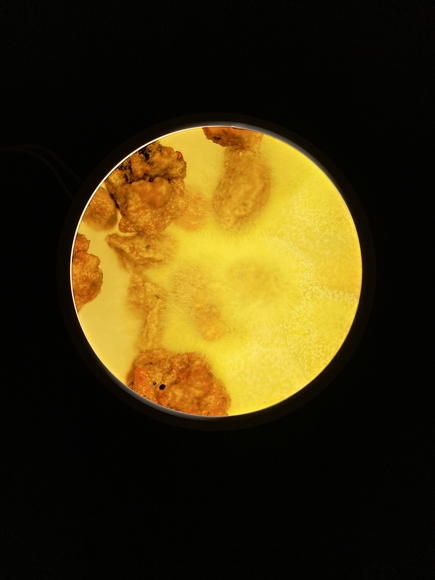

Stephanie Lindquist is very interesting because she is mixing science (using real earth from different geographies) to then make abstract/photorealistic images of molds/real living organisms from the petri dishes she grows them in. For what you see as the connection between the Black woman/family/ history, the earth, life, song…

Erica Maria Littlejohn, Art by .E Lewis, Kehayr Brown-Ransaw, and Nicole Davis – all that conversation within textiles, storytelling, history of and new ideas in quilting.

Ta-Coumba Aiken, Christopher E. Harrison, and Lela Pierce – About the portals or vortexes, pathways to new worlds, new galaxies, transformation, transportation, and metamorphosis.

How do you see this group of works speaking specifically to life in the Midwest? How does the concept of "home" find expression in this exhibition?

Specifically with the colors, the crispness of choices and textures, the risk-taking, and the otherworldly visuals made in the exhibition. I find the focus on blackness, but the way in which it has been ingrained yet hidden to the masses to a degree, very midwestern. The Midwest for me is a different conversation than the coasts when we speak of "Black Abstraction/Abstraction." Our conversations and creative works have to function in a very passive aggressive, very violent and insidious, racially biased system. We function within the highest disparities for education, jobs, housing, and food access. These Midwest artists are the new pioneers, the new "great migration." We are the pathfinders and the scouts in a hostile world. Yet, per our Black culture, our spiritual connections, our food, dress, sounds, and stories, we still make things beautiful, loving, engaging, complex, simplified, but thought provoking; magical, historically sound, and connected experiences. I am glad we are talking and writing about these artists and this exhibition, but what I find particularly Midwest and connected to home is this: we all met at the family table (i.e. over Zoom, studio visits, phone calls). We will break bread, drink, laugh, and tell stories, make songs and celebrate no matter the circumstances we live in or that are in front of us in our life’s journey as Black abstractionists/Black Creatives.

This is what can’t be captured in academia or in a book or via critique. This is about what I have so longed to articulate since arriving in art school. We are a family based on life experiential activities. Art made from the knowledge of common experiences that deserve the time and care given to them by these black artists.

Lastly: Christopher Harrison accompanied me to Senegal, Africa, for an Artist's residency with The Global Art Project founded and ran by Carl Heyward out to the Bay Area. Short of it is, we share fragments and make solo and collaborative work and we function mostly on social media other than meeting up for these residencies (Venice, Italy, Mazatlan, MX, and Senegal, Africa, for me). So, fragments are important to me and this work; family/community/social interaction is important to me and this work. For Chris and I, working and living here in the Midwest, we went "Home" to the motherland together, we swam off the coast of Senegal in the Atlantic almost with tears in our eyes. Chris and I ate from the same bowl as the locals and were adopted by the Baye Fall muslim sect in Senegal.

This exhibition is my way of bringing us "home" to a place like Africa for Chris and I. A way back to our histories and families, foods and love. Sounds, and colors, connections to the earth, water, and sky. Back to ancient ways though we live in the here and now. This exhibition is the beginning of the conversations and pathways back to each other. Back home, for us the Midwest is home. Like these artists, like Chris and I’s trip, we gather our fragments, we bring material, ideas, and processes together for community for a sense of belonging. A way to actually live and engage rather that long for – Home. I wanted to give my people that feeling I had when I first stepped out of the plane and smelled the air and felt the sun in Africa. I wanted to finally feel at home – here in the Midwest. I wanted this to be my response to the death of George Floyd. I wanted to take the start of the body, the protests, the activism, and frame it in a way that the world couldn’t ignore or deny.

You are a practicing artist yourself. How do you describe your own work, and do you see curation as an extension of your studio practice or something entirely separate?

I feel my work is best described as abstraction with a deep critical eye for the representational. I live and thrive within that tension of where the representation tears apart to a new time, place, and space. My work is rooted in the fragmentation of histories and processes, materials, ideas, and philosophies. My work is always rooted in Blackness and life experience. Visually I take from the literal street. I look at the "street" two ways – As my grandmother and elders have always said, keep out the streets and never bring the street to the house. Second is the "Street" where we all meet – the rich, poor, addicted, dominant, uneducated, or genius; folks who work or who are out of work, with whatever gender or pronoun or identity you choose. The street is where socially, community-wise, and even educationally we can thrive.

For example: Visually, the city paints over a tag, and then the art center gets a grant to make a "real mural," and then the mural gets tagged again but by the gangs. Then we let the place fall to disrepair because of the geography and politics. Next thing we know it's a neighborhood communication board. Posters and ads, information gets stapled and glued to the wall. After a time, mother nature takes over, and you see weathering and patinas from iron from the metal structure above staining all those visuals that have changed over time. So, what I am saying is I love experiencing the spaces, geographies, and cultures of different worlds. I like to see what I call the battle over territory played out on city, town, community walls, buildings, and streets.

After talking to so many outlets and artists and family and friends about this exhibition, I feel I am no longer able to say I am an "artist" per se. But rather I feel I am a "creative." I put out an album in 2011, I have done voice-over work since 2005, I have been in art education since my undergraduate work at Penn State, and have been teaching in Minnesota since grad school. Consistently for the Minnesota State College system for 18 years and counting, I’ve done work in the community and the private sector focusing on the Arts and Arts education – which includes activism at times. I work collaboratively with over 60 different international artists with a platform on social media outlets like Facebook and Instagram. Now, yes, outside of the academic setting I have curated this exhibition with the help of SooVAC, Clarence Morgan, and I can’t forget Caroline Kent as mentors. So at times, I am still a student. I see no difference between studio, curation, voice-over, the collaborative work, the education piece – and being open to growing more as I learn and experience more. I feel I just live the life of a Black Creative.

All artwork is an abstraction, in a way – flattening out our lived realities into two dimensions or rendering them as objects, even in the most "photorealistic" work – but obviously some artists embrace abstraction more than others, yourself included. Zooming out from the diverse approaches to abstraction from Black artists in this exhibition, I wonder if we can extrapolate the concept of being a "Black American" as an abstraction as well, a simplification of something much larger and deeper? Perhaps "America" itself – socially, culturally, and in its erasure of histories – is the real abstraction?

For me I explain it like this, the same way I teach my students. How can you abstract what you do not actually know? On what basis are you making your shifts, your moves, your material choices? What are you reading or experiencing that is informing the visuals you want your audience to engage with?

Imagine: your whole educational and art training being from your head as a child (meaning what most folks tell you is good art and what you should make), your experience in K-12 and then your college career. That whole process was rooted, focused, arranged, and funded based on what I would call reverse Critical Race Theory, but within my whole education. Not just CRT focused on law and law interpretation, which I believe is the only real place CRT is used on the daily – I could be wrong, but that was my understanding.

All the philosophies, ideas, images, and histories are from the white, Western, male, violent, and money-driven culture. A lot of times based in and on hate for women, BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, our migrant communities, and the physically and mentally vulnerable. Then on top of it, we have our histories, images, philosophies, ideas, inventions, and pathways stolen, raped, sold, and colonized. All for us to have to pay to learn and function in the above system. But now we have to think Abstractly, creatively, economically, and so on to research, investigate, and uncover what was stolen, appropriated, and taught wrong in the first place.

What I am saying about what I described is that it's a very abstract way of having to think, function, articulate, and survive in a world that hates you and started you off as a way to make money and money only from the bodies of you and your families.

Being a Black American means I have no way of really finding out where my home truly is without again asking the same system I described above to analyze my DNA to prove where they stole my ancestry and my ability to start, for lack of a better word, in reality of how I came into this world. Having to always function and survive via unfamiliar and uncomfortable ways is no longer that. The Abstraction, the unknown, the world of so many options (but yet limited and controlled options) and ways has always been my world as a black man. Like being told you are free. But what does freedom really mean? Exactly – pretty darn abstract if you ask me.

We are now, due to Covid and other factors, in a place where all the understandable representational and photo realistic options are actually what is "not real." Or not based in a sustainable reality. Those of us who have had to shift identities, philosophies, tastes, geographies, and traditions by force. The only way to keep the kids and your ways alive is to think and be abstract. You aren’t allowed in the front door most of the time. Even if you go in the front way, there’s always a hustle is what I’ve been taught.

The show’s title is inspired by a passage from Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, in which Butler says "The only lasting truth is change." The work here, though abstracted, speaks to lived realities in this changing world, and there is a compelling combination in this exhibition of hearkening back – to traditional crafts and practices – and looking forward to an unknown future. Can you speak to how these artists are making work not just reactively in response to our times but proactively as well? What role does art have in shaping that unknown future?

This is the unknown future. This whole process and investigation has been a pathfinding mission to say, Yes, the Midwest, America, is way - ABSTRACT - in all its opportunities and all its faults. The work and the artists along with the vision is another example of real life experience within the Black community and culture, where like Sun Ra, like Octavia, like Lorde, Baldwin, Ellison. All in their ways and histories are abstract and otherworldly. I don’t feel I nor the show is a response to the times. It's a true real-time call to action with clues like the first quilts on the Underground Railroad. We are saying, Here are the paths. But as we know, the same path can lead individuals to different resolutions and geographies.

We are saying we are HERE. We are HERE to STAY. We have made the MIDWEST - HOME. Yes, choice, but ask yourself, what kind of choice(s).

I will end by referencing my students again, because I teach out of the love of being alive and available for those who want to question. You can come see me or talk to me. But with that – I teach them, you, me, our families, and what we offer to the world – is a true example of our worth, power, and strength. Our role is to find a way to communicate in this complex, fast-paced, and very nonlinear world. The most successful and the most long lasting ecosystems are those that have the greatest diversity. I feel this is the beginning of a bigger conversation and movement and way of life for Black artists. A place where we can function with the adaptable tools and processes within our Abstract worlds and show another way to stability. Specifically, economic stability, by inspiring our communities to invest in these visions and objects. Our role speaking to Nina Simone's declaration, "An artist's duty is to reflect the times." The times are Black and abstraction right now is the galaxy among many galaxies among the stars. Clarence Morgan once told me, "Greg – you like to show people the mirror, but you have to understand that they don’t always like their reflection." But this is our reflection, A Black reflection, in all its complexities and contradictions, all the vulnerability and trauma. We are focused on how beautiful and resilient the Black reflection (including the body) truly is.

Change is God-Take Root Among the Stars: Black Abstraction in the Midwest is on view at Soo Visual Art Center through July 30, with an artist panel discussion and closing reception from 5-8pm. For more info, visit SooVAC's website, or follow @soovac on Instagram to see images of the exhibition and video interviews with some of the artists. You can follow Gregory J. Rose on Instagram @gregoryjrosestudios.

Banner image courtesy of SooVAC.