What Makes A Good Still Life?

On the second floor of the Regis Center for Art, there is a small room filled with the stuff of nightmares. It doesn’t have dangerous chemicals or spinning tablesaw blades or molten metal like so many other studios in the art facility. No, this room can’t hurt you, but when you open the door and turn on the lights, what you’ll find staring back at you is a cluttered menagerie of mannequins, skulls, bones, and shelf after shelf of strange old bric-a-brac.

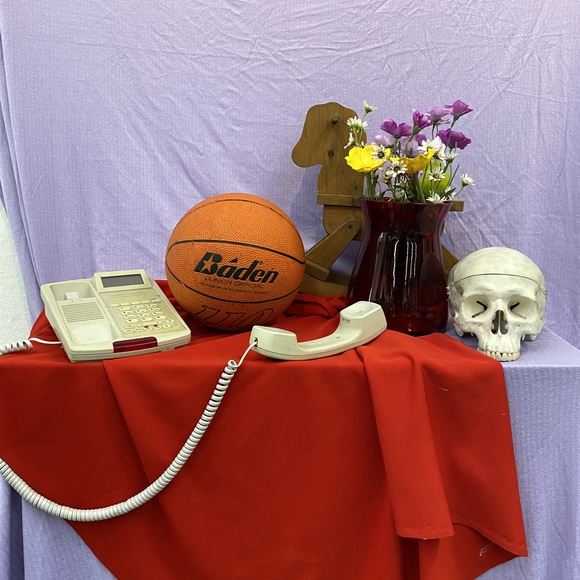

This is the Props Closet, home to a wide assortment of would-be objets d’art: empty wine bottles, fake flowers, an old trumpet, a plastic merry-go-round horse, and a whole bunch of mannequins in various states of limblessness. It’s like the everything aisle at a secondhand store, except these items don’t just sit around collecting dust — they get put to use: this is the stuff of the still life.

Still life is a long tradition in Western art, a way for students and professionals alike to hone their observational skills through drawing and painting. Conceptually, they offer the chance to meditate on mortality (as in the fruit, game, and skulls beloved by Dutch Renaissance painters), the metaphysical (as in Giorgio de Chirico’s strangely symbolic compositions), the minimalist (see Giorgio Morandi’s endless fascination with neutral vessels), and the decadent (Wayne Thiebaud’s thickly painted birthday cakes and ice cream cones are enough to make your mouth water). Some historians even trace the very beginning of the Modern era to the moment that Paul Cézanne broke the plane of a table behind a basket of fruit. Who says still life painting has to be boring?

But the question before any artist facing a blank canvas is what to put on it. Luckily for students in Lecturer Emma Beatrez’s Intro to Painting class this semester, that decision has already been made for them: Beatrez has created two set-ups to work from on opposite sides of the studio. On the left, a classical bust sits next to a pile of grapes, an open pair of scissors, a handful of seashells, a plastic bouquet of baby’s breath, and the old trumpet, all atop a mixture of green, orange, and red fabric. On the opposite wall, on the much cooler tones of blue and purple fabric, the oranges of the carousel horse and a basketball play off the yellows of some flowers, a lemon, and the reflection of light off of a metal fan blade.

“I usually do two half-circle set-ups because the classrooms are so full,” says Beatrez, an accomplished painter herself. “I have to think about it in the round; it’s not just one perspective I’m thinking about. The relationships have to be interesting all the way around.”

Indeed, as you move from easel to easel, you get a full 180 degree view of each set-up, noticing different connections vicariously through the students’ observations: how the lines in the fanblade match those in the basketball and how that connects to the line of the plastic skull sitting at the horse’s feet; or how the white tones of the marble bust and the seashells both pick up the warmth of the orange cloth underneath.

The students have been tasked, Beatrez explains, with “focusing on the interaction of two complementary color pairs” — colors on the opposing sides of the color wheel — “so the students have to mix up a completely harmonious palette ahead of time with precise neutral grays and hues in between.” The works start as grayscale underpaintings to help the students isolate the shadows and tonalities before going back in with full color on top, and this transition is fascinating to watch as you move around the room. For an intro class, these students are already quite technically adept. Beatrez agrees. “I’m very impressed.”

Other classes, meanwhile, have been digging into still life with a different approach. Associate Professor Mathew Zefeldt’s Intro to Painting class began by recreating famous compositions in umber and white before diving into creating their own. “This doesn’t reflect your life,” Zefeldt acknowledges, pointing to the elaborate tablescapes in the old masters’ works. “Your place maybe doesn’t have crystals and skulls and oysters; maybe it’s iPhones and textbooks.” For their follow-up assignment, he explains, “I want students to bring things in that are unfamiliar to painting for them.”

Lecturer Christopher Harrison takes a similar approach, allowing his students to paint from their own photos. “Every piece that an artist does is a self-portrait, in one way or the other, even if it’s a landscape or an abstract,” he says. “I tell my students, what’s the story you want to tell? What is that story you can bring out that people can relate to to tell people about yourself or about the time that you’re in.”

A wide range of still life subjects emerged in both classes: piles of art supplies, designer handbags, chessboards, elaborate floral displays, the contents of a junk drawer. Many in Zefeldt’s class brought in photos with text — on paint tubes, book spines, and perfume bottles — adding an extra challenge to realistically render.

“The use of branding feels new and contemporary, something that the old paintings we copied don’t have,” Zefeldt says. In a world of branded identity, in which what we buy and wear and eat and support so thoroughly bolsters our identity as individuals, there is an added level of personal connection to these compositions — and perhaps a mordant touch of momento mori, looking ahead to our own mortality not through the bones we leave behind so much as the plastic bottles.

Lecturer Melissa Cooke Benson, who teaches drawing and is a masterful realist in her own practice, considers still life to be a deeply personal genre. “I think one of the captivating elements of still life is how personal and revealing a collection of objects can be,” she says. “Those objects tell a story about the person and their environment, sometimes revealing their inner thoughts.” It is a genre that is still relevant far beyond the classroom, she says, pointing to contemporary painters Anna Valdez, Daniel Gordon, Lucia Hierro, and others making new work with the old practice.

Whether using these set-ups for formal exercise, historical learning, or conceptual self-portraiture, it seems that still life is still very much alive. Artists at every level can learn something from the practice, including the instructors at Regis. When not talking to students about their paintings, Zefeldt used the class time to work on his own composition of hand sanitizer, potted plants, a chunky orange rock, and a Menards coffee mug. And the question of what makes a good still life, as with all art, remains stubbornly subjective — sometimes the angle, crop, and color of a composition can have more impact than the objects alone, whether they came from the artist’s life or just the creepy closet down the hall. This semester, there have been as many answers to that question as there have been students in the studios; the proof, as always, is on the easels.