Austria's 2024 Federal Election: Turning Point for the Far Right

By Ander Kierig, University of Minnesota

Eleven Years of Turmoil

Exactly eleven years prior to Austria's Federal Election on September 29th, 2024. I stood in a corner of the offices of the Alliance for Austria's Future (BZÖ) chatting with my contacts in the party. Their hopes of remaining a federal parliamentary party hung by a thread. Originally founded in 2005 as a moderate governing splinter from the evermore far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ), the BZÖ had attempted to reconstitute itself as a social centrist and economically liberal party in the mould of the German FDP (Free Democratic Party). Numerous vestiges of its far-right past remained. Pictures of and a memorial to its late founder, Jörg Haider, adorned a wall in the large room in which we'd gathered. Nevertheless, the BZÖ's federal election candidates appeared to be sincere in their desire to build a "modern middle" party. However, they were not successful, falling short of the 4% national threshold by a few thousand votes (1). While the BZÖ might be gone, the legacy of their party's firebrand founder continues to echo into the present, as the 2013 election also marked a break in the Austrian political landscape.

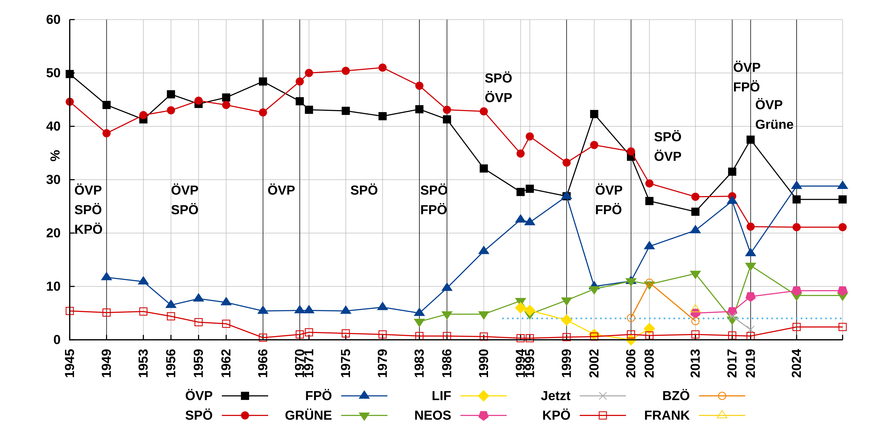

For most of Austria's post-World War II history, the country, its constituent Länder (states), and even its municipalities had been governed by a system known as Proporz, whereby political power was primarily shared between the center-left Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) and the center-right (Christian Democratic) People's Party (ÖVP), and based on the number of votes each party received. On a formal level this meant that villages, cities, and states were almost always governed by a coalition of the SPÖ and ÖVP with the actual composition of the cabinet determined by election results. The purpose of Proporz was to eliminate the instability of governments that plagued interwar Austria and ensure the broadest possible interest in preserving the constitutional order. At the same time, a 4% vote-share requirement (similar to Germany's 5%) to receive seats in the Nationalrat or state parliaments further ensured that the formation of stable governments was not impeded by numerous small parties threatening to withhold critical support. On the federal level, there was no legally mandated Proporz system, but the small number of parties and a political culture that valued stability and compromise over ideological victories more or less ensured that the only way to form a stable majority government was a combination of SPÖ and ÖVP. If the fracturing of this system began with the emergence of the Greens on the left and the FPÖ on the far-right in the 1980s, 2013 marked the last gasps of the Proporz party system, as seven parties had legitimate chances to reach the 4% threshold to elect members of the Nationalrat (the lower house of the Austrian parliament). The aforementioned SPÖ, ÖVP, FPÖ, and BZÖ, the Greens, the right-wing populist Team Stronach, and the centrist NEOS all reached the 4% threshold, with only the BZÖ falling short. And while the resulting government was a coalition of the SPÖ and ÖVP, its majority was small, and its leading figures unhappy, with both parties’ leaders replaced before the next election.

In the years since, the political scene has been the site of uncharacteristic turmoil: the 2017 Election resulted in the rebranded and "modernized" Christian Democrats forming a government with the FPÖ under the 31 year-old Sebastian Kurz, only to collapse two years later in the wake of a scandal. During the months leading up to the 2017 elections, undercover journalists recorded a video of FPÖ leader Heinz-Christian Strache pleading with a woman pretending to be a Russian oligarch's niece for party financing, which would help turn Austria into an illiberal democracy in the style of Victor Orban’s Hungary The collapse of that ÖVP-FPÖ coalition government after the so-called Ibiza-Affäre (2) led to the first ever technocratic government under a former Constitutional Court justice (and first woman chancellor, Brigitte Bierlein), and subsequently: the resulting election yielded an ÖVP-Green coalition, the first ever Austrian federal government featuring the Greens.

The ÖVP-Greens government navigated the COVID-19 Pandemic, the backlash against masks and vaccine mandates, Russia's second invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and economic turmoil relatively successfully, but nevertheless suffered from a variety of attacks from the far-right, many of which bore the hallmarks of foreign (ie., Russian) misinformation and influence campaigns.

Campaign Themes

Austria's 2024 election featured parties attempting to play to their strengths. FPÖ voters were driven by the party’s core themes around immigration, policing, neutrality, and security, while ÖVP voters chose the performance of the ÖVP-led coalition. SPÖ voters concentrated on social and economic justice (healthcare, inflation, and income inequality), while the Greens focused on the environment, and the NEOS education, the economy, and inflation.

In the end, and as in the Dutch elections of November 2023, the far-right populist party was the most successful party at making its case with voters. Similar to the Dutch case with the PVV (Party for Freedom), the FPÖ’s successes were fueled in part by opposition to EU intervention in Ukraine following Russia's 2022 invasion (3). However, and unlike in the Netherlands, Austria features a unique twist to far-right politics: its neutrality, which the far-right has weaponized regarding support for Ukraine. Enshrined in the constitution after 1945 as a condition for avoiding Cold War partition (as happened with occupied Germany), neutrality has long been considered the keystone of Austrian foreign policy outside the EU, and by politicians across the ideological spectrum (4). In part due to its strong connections to the United Russia Party, and in light of its ongoing refusal to condemn Russian actions while spreading Russian propaganda about the war in Ukraine, the Austrian far-right (including the FPÖ) has used Austrian Neutrality to condemn the governing parties as reckless warmongers. Indeed, weaponizing NATO and allied support for Ukraine was first attempted during the initial 2014 Russian invasion in the E.U. parliamentary elections, as videos of tanks loaded on trains in the US or other NATO member states purportedly moved through Austrian cities to start World War III (5). Even as "deepfake" and AI generated images and video are now easier to create than ever and therefore far more dangerous, the spread of misinformation was already rampant in 2014. Automated "bot" accounts on social media platforms and further distribution by FPÖ-allied media played a not-so-insignificant role in spreading these messages during this election.

2024 Election Results

The surge in the popularity of the FPÖ notwithstanding, the 2024 election marks the first time in post-war Austrian history that neither the ÖVP nor SPÖ led on election night, a genuinely remarkable result.

In turn, the election portends deep trouble for the SPÖ. Having been part of the government almost continuously from 1945 to 2017, their failure to meaningfully improve their performance from 2019 and reverse their continued decline from 2017, and despite not participating in an unpopular government, should be seen as a warning sign for their political future. The failure of the KPÖ--a mix of disaffected socialists formerly supporting the SPÖ to outright communists--is no doubt disappointing, but their continued success at the local and state level, notably in Steiermark and Salzburg, makes it likely that they could overcome the 4% electoral hurdle by the next election.

Thunder on the Right

By tradition, the leading party will have the first opportunity to form a government. This means the FPÖ, under the leadership of the most radical leader in their history, Herbert Kickl (6). Unlike previous FPÖ leaders who publicly kept the most extreme elements of the far-right at a distance, Kickl has openly embraced them. Shortly before taking office as FPÖ leader in 2021, he called the Identitäre Bewegung (Identitarian Movement), an organization Austrian intelligence services deem right-wing extremist with ties to neo-Nazis, an “interesting project that is worthy of support.” Kickl did so only days after the FPÖ’s then interim leader and governing board declared that membership in the group to be incompatible with membership in the party (7). His taking office as party leader was made possible only by ousting the relatively moderate (by FPÖ standards) Norbert Hofer, a politician known for his affable personality and charm. While some might argue that they share similar views, Kickl’s embrace of the extreme-right Identitarians in contradiction with other FPÖ leaders and his aggressive articulation of hard-line anti-immigration policies using rhetoric more commonly heard in the 1920s and 30s underscore the end of FPÖ attempts to appear relatively moderate as they had under Strache and Hofer.

Kickl was previously Minister of the Interior, with oversight over policing, intelligence, and border controls. Coincidentally, Kickl is also one of the most tightly bound to Russian influence networks and it is likely that he will, in conjunction with the Hungarian and Slovak governments, attempt to delay or block European defense and security efforts as well as additional aid to Ukraine (8). Just as during the 2017-2019 ÖVP-FPÖ coalition, which Kickl directly managed the Austrian intelligence services, an FPÖ government makes it very likely that Austria will be roundly excluded from EU and broader western intelligence and security cooperation, while Russian intelligence agencies would continue to use Austria as a major staging and transit point for operations throughout Europe and even further abroad. In sum, Austria would face increasing isolation from its EU and Western allies at all levels and in all areas of cooperation (9).

Who Governs?

Kickl has also made it clear that any FPÖ led coalition government will only be formed if Federal President Van der Bellen appoints him chancellor (10). Van der Bellen, formerly a member of the Green Party, however has the power to give the task of attempting to form a government to the party that he deems most likely to succeed (11). As of this writing in late-October, Van der Bellen tasked the current chancellor and moderate leader of the ÖVP Karl Nehammer with responsibility for forming a new government, arguing that Kickl’s FPÖ, despite coming first in the election, had no hope of forming a government with no willing coalition partners (12). The most likely outcome will be for a new coalition led by the ÖVP, with the SPÖ and centrist NEOS party as the junior partners. For the current leadership of the ÖVP, Kickl and the FPÖ are simply too toxic and their views too extreme to contemplate joining a coalition with them, let alone one in which the ÖVP would be the junior partner.

Kickl however is not without cards to play. On October 24th, the FPÖ nominated Walter Rosenkranz, a close Kickl ally to the post of First President of the Nationalrat. The three presidents are selected by the three largest parties and in practice primarily serve to facilitate the business of the legislature. Rosenkranz seems poised to use this position to hinder the work of the new coalition government as much as possible. This is also a further blow to FPÖ moderates like Hofer, who previously served as the FPÖ’s nominee as Third President of the Nationalrat. As with Kickl, Rosenkranz has a reputation for extremism, with the president of the largest organization for Austrian Jews describing him as a “brown [ie., Nazi] wolf in blue [FPÖ color] clothes (13).” While it is possible that he will use his position in a relatively non-partisan way, his selection as the FPÖ’s candidate over the previously serving Hofer makes that highly unlikely.

Conclusion

Austria's election marks a significant turning point for the far right, achieving their first ever first-place finish in a national election. It is a remarkable turn of events since 2019, for a party whose longtime leader was caught soliciting illicit funds from a person they thought to be a Russian oligarch's niece. For the mainstream parties that up to this point had been the ruling parties (i.e., the ÖVP and SPÖ), the chance to form a new grand coalition is perhaps a meaningful opportunity for both parties to demonstrate their willingness and ability to cooperate productively and win back support previously lost to the FPÖ. Finally, this moment suggests that, if mainstream parties are to counter the rise of the extreme illiberal right in Europe, whether the Alternative for Germany (AfD) in Germany, the Freedom Party (PVV) in the Netherlands, or the FPÖ itself they must be both smart and quick in addressing the meaningful problems that voters for these parties face, while also delegitimizing the factually incorrect narratives those parties use to garner support.

Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author's, and do not reflect the views of the Center for Austrian Studies or its affiliates at the University of Minnesota.

Author Bio

Ander Kierig works at the University of Minnesota Libraries and earned an MA in International Affairs and BA in European History, both from the University of Oklahoma. Kierig lived in Austria from 2011 to 2015 while studying Politics, History, German, and Law at the Paris Lodron Universität Salzburg.

Endnotes:

1. For a general overview of the 2013 Election written and published shortly thereafter: Dolezal, Martin, and Eva Zeglovits. 2014. “Almost an Earthquake: The Austrian Parliamentary Election of 2013.” West European Politics 37 (3): 644–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2024.2397629

2. The original videos can be found on the websites of the Süddeutsche Zeitung (https://www.sueddeutsche.de/projekte/artikel/politik/das-strache-video-e335766/) or Der Spiegel (https://www.spiegel.de/video/fpoe-chef-heinz-christian-strache-die-videofalle-video-99027174.html), both accessed 11 October 2024.

3. On the Dutch case, see: Holsteyn, Joop J. M. van, and Galen A. Irwin. 2024. “The Dutch Parliamentary Elections of November 2023.” West European Politics, published online 11 September 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2024.2397629 (accessed 11 October 2024). ORF polling on voter motives for the primary themes of the Austrian election: https://orf.at/wahl/nr24/wahlmotive/themen-wahlkampf (accessed 11 October 2024)

4. Hence why Austria avoided joining the organizations that evolved into the European Union until after the collapse of the Soviet Union and even then, only with the tacit approval of the Russian government.

5. This video features Ewald Stadler, a former member of the FPÖ and BZÖ and former member of the Nationalrat and European Parliament. Stadler continues to be very active in extreme-right circles across Central Europe. This video comes from his unsuccessful 2014 European Parliament campaign after founding his own short lived “Reform Konservativen” party. “MEP Ewald Stadler REKOS Panzertransport durch Österreich Ukraine Krise 29 04 2014” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=51zs9-OAJOQ (accessed 22 October 2024)

6. Although Kickl rejects any comparisons to National Socialism, he uses terms such as “Volkskanzler” (“[ethnically German] people’s chancellor” which also appeared in Nazi rhetoric from the 1920s and 1930s to describe Hitler.

7.“Kickl: ‘Die Identitären sind für mich so etwas wie eine NGO von rechts’” Kurier (9 June 2021). https://kurier.at/politik/inland/kickl-die-identitaeren-sind-fuer-mich-so-etwas-wie-eine-ngo-von-rechts/401407830 (accessed 18 October 2024)

8. Lindholm, Rickard. "Austrians doubling down on neutrality means European security faces uphill battle." 1 October 2024. Wilson Center, Washington D.C. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/austrians-doubling-down-neutrality-means-european-security-faces-uphill-battle (Accessed 12 October 2024)

9. ibid.

10. Stepan, Max. "Kickl zu Van der Bellen: "FPÖ-Regierung nur mit mir als Bundeskanzler." 5 October 2024. Der Standard https://www.derstandard.at/story/3000000239567/kickl-zu-van-der-bellen-fpoe-regierung-nur-mit-mir-als-bundeskanzler (accessed 12 October 2024)

11. Traditionally, the Austrian federal president resigns any party memberships upon taking office; Marchart, Jan Michael, Walter Müller, and Michael Völker. "Wie ÖVP und SPÖ in eine Regierung finden könnten – und wo es dabei holpert." 12 October 2024. Der Standard. https://www.derstandard.at/story/3000000240424/wie-oevp-und-spoe-in-eine-regierung-finden-koennten-und-wo-es-dabei-holpert (Accessed 12 October 2024)

12. Murphy, Francois. “Austrian president tasks centre-right, not far right, with forming govt.” 22 October 2024. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/austrian-conservatives-again-rule-out-far-right-alliance-after-leaders-meet-2024-10-15/ (accessed 23 October 2024)

13. Traar, Christina. “Oskar Deutsch warnt Nationalrat vor FPÖ-Mann Rosenkranz.” 23 October 2024. Kleine Zeitung. https://www.kleinezeitung.at/politik/innenpolitik/18999415/deutsch-warnt-nationalrat-vor-fpoe-mann-rosenkranz (Accessed 23 October 2024)