CAS Stories: The Soul of the Austrian Pianist and Composer Joe Zawinul

The Soul of the Austrian Pianist and Composer Joe Zawinul

By Mikkel Vad

Mikkel Vad is a PhD candidate in the Department of Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies. His dissertation, "April in Paris, Autumn in New York: European Jazz in the US, 1945–1970s," explores the transatlantic journeys that transformed jazz—a genre and culture that is often identified as quintessentially American. Jazz is, nevertheless, a music that, from its earliest years, became deeply embedded in European culture and marked by routes of dissemination that go from and back to the US. At the heart of his research is the question: What happens when jazz returns “home”? Mikkel Vad traces the dissemination and reception of European jazz recordings in the US, the musical lives of Europeans who went to the US, and the returns of American musicians who went to Europe but came back to the US.

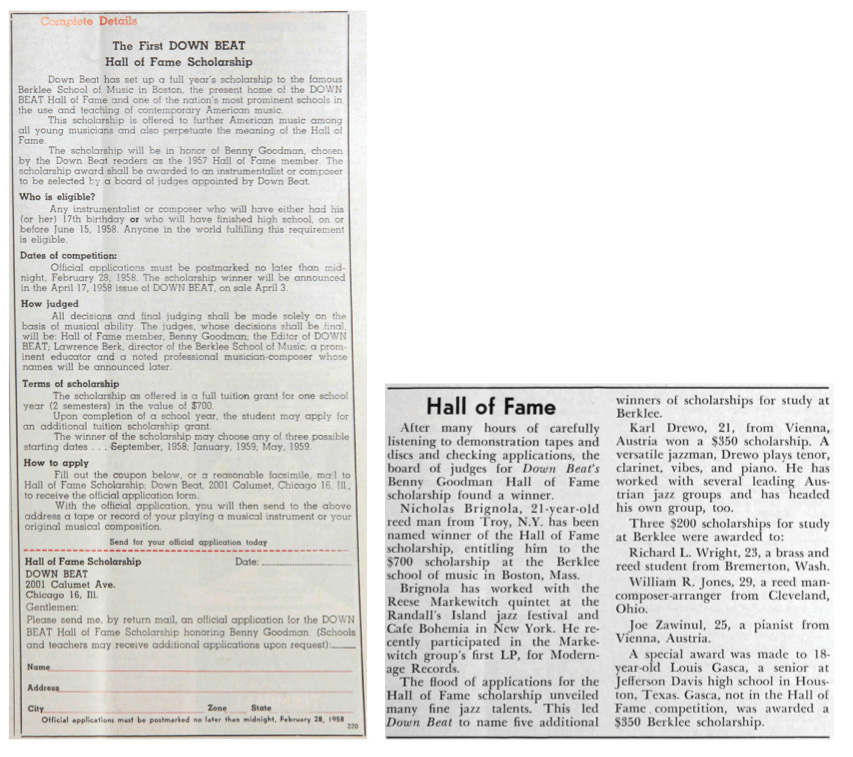

With the support of the 2019 CAS Summer Research Grant, Vad went to the Library of Congress in Washington, DC where he carried out archival research related to the Austrian pianist and composer Joe Zawinul (1932–2007), who is a case study for his dissertation. Vad traces Zawinul's career from a young piano prodigy who came to the United States and enrolled at Berklee College of Music in the late 1950s, through his career with Dinah Washington, Cannonball Adderley, and Miles Davis, to his success with the fusion band Weather Report in the 1970s.

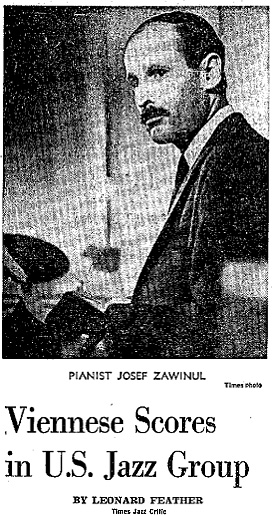

Joe Zawinul still had most of his hair on his soon-to-be balding pate and had not yet grown his iconic moustache when he arrived in New York City on a cold January day in 1959. The young Austrian pianist had, as he later recounted, become “obsessed with wanting to go to America and learn how to play music. . . . I had to get to the United States if I was going to grow as a musician,” he concluded. “I had to have contact with the music as a living force. And I couldn’t get this in Vienna.”

Zawinul had won a scholarship to attend the famed Berklee jazz conservatory in Boston, but the trajectory of his education reveals that, for him, the place to “find things” was perhaps not within the institutional frames of a conservatory. Zawinul later rationalized that he had come to the US “with the purpose to kick asses,” and that he had “a lot of learning” to do—‟not in school, but out there with the musicians.” Kicking asses is, perhaps, more easily done outside the confines of formal education: Zawinul dropped out of school after a few weeks and joined Maynard Ferguson’s big band. Through the sixties, Zawinul established himself as a reliable sideman for musicians such as Ferguson (who also secured him a green card), Dinah Washington, and, most prominently, Julian “Cannonball” Adderley. His work as a composer flourished under Adderley, for whom he wrote the hit “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy.” In 1969, he provided material for Miles Davis’s In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. In 1970, he formed the band Weather Report (the other key bandmember being Wayne Shorter), which became the most prominent fusion band in jazz.

Joe Zawinul, perhaps more than any European musician, has become part of the American jazz canon. As such, he became a symbol of jazz as a transnational, yet American—and particularly African American—art form. Conrad Silvert summarized this anomaly in the opening to his 1978 Down Beat portrait article:

"Although a compelling argument can be made that jazz has become the world’s most international art form, suffering from few barriers of geography, language or race, it remains true that the great majority of jazz innovators have been American blacks. The exception to this rule has been the emergence of Josef Zawinul—a white man born in Austria—as one of jazz’s prime innovators."

In the chapter for my dissertation supported by the Center for Austrian Studies summer grant, I take up the issues Silvert identifies and focus on how Zawinul fared “out there with the musicians,” particularly in terms of how he negotiated his role as a white Austrian working with, primarily, African American musicians in a black musical style.

After a few years in the US, Zawinul was happy to denounce his origins. As Down Beat reported in 1966:

"He refuses to attach any particular significance to the fact that he is one of a handful of non-American musicians to have achieved any prominence in jazz, let alone to have contributed something to it. . . . To hear Zawinul tell it, there’s nothing remarkable in his having attained perfect mastery of modern jazz piano unaided by any direct contact with U.S. jazzmen, major or minor, in the unsettling atmosphere of a four-power-ruled Vienna in the years immediately after World War II."

Indeed, the big hit Zawinul composed for Cannonball Adderley’s band, “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” showcases all the features of African American soul jazz.

Here, Zawinul liberally sprinkles blues inflections across his own solo, aided by the attack and timbre of the electric piano. Add to this the live setting of the recording (which was in fact created in the studio as a kind of “fake” live concert with an invited audience), with its background noise of clinking bottles, talking, and applause that gives the track a feeling of liveness and authenticity. The hollers from the audience work in a gospel-like call-and-response to Cannonball Adderley’s opening sermon about confronting adversity. In the midst of the civil rights era, this would not have been a surprising message from a leading, black soul jazz musician. It was surprising, however, that the composer behind it was a white, Austrian fellow.

For Zawinul, musical appropriation of black styles was part of a personal identity politics in which he increasingly fashioned himself as a cosmopolitan, “gypsy” character (a word he used about himself several times). Pointing back to his Austrian heritage, he stated:

"The mixing of races and the mixing of cultures creates the greatest of all things. This is my theory. This is what I really believe in. Not only in the 20th century, but period. . . . Take Austria, for example, when it was like a small United States, with all those different countries under one banner, the Austro-Hungary Empire. There were Czechs, Hungarians, Serbians, Croatians, people from parts of Asia, it covered so much, man. And all these people met in a central melting pot, which at the time was Vienna. It created a completely new world and way of thought."

This comparison of Austria and the United States is striking in its romanticism. Zawinul, of course, was born after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and his vision of it is laden with imperial nostalgia. His imagination of a multiethnic, multiracial empire was troublingly untroubled by its imperial past. This attitude was equaled by his self-image of his affinity with African American culture:

"To me, they [black people] are the easiest to understand, the closest to my environment. The way I grew up, you know—joke-wise, fun life, big families and all that. A simple life—not too much dough, but a lot of humor, and very close. People are alike all over the world in a way."

Many white critics of the sixties and seventies were only too happy to accept Zawinul’s position in jazz music as proof of its universalism. In the words of one reviewer, Zawinul was “proof that soul jazz is not the sole property of the ‘soul brother.’” Observations like these should be seen in the context of the civil rights era and (white) dreams of a postracial society. Here, Zawinul becomes the poster boy for a musical colorblindness in which the blackness of jazz is almost coincidental and where the black nationalist aesthetics of the era loom in the background as an aggressive and nonsensical position.

Zawinul’s soulfulness was, however, also noted by black musicians and the African American press. The Los Angeles Sentinel’s Gertrude Gipson wrote: “[Cannonball’s music] has a solid soul base, but it’s broad enough to include his blue-eyed pianist, Josef Zawinul. Born in Austria, he wrote ’Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,’ and proves he’s a ‘brother’ under the skin by the way he plays a funky gospel beat.” Leaving aside the fact that Zawinul had brown eyes, this is a remarkable acknowledgement of the power of Zawinul’s music. We should note, however, that Gipson does not use Zawinul as proof that colorblind music transcends race.

Zawinul’s musician colleagues were perhaps especially attuned to his musical characteristics and the ease with which cultural contradictions coexisted in his music. The bassist Walter Booker, who played with Zawinul in Cannonball Adderley’s group, said: “It’s funny, because Joe played piano with Dinah Washington, playing the blues, and he wasn’t supposed to be able to play that kind of stuff, being white and from Europe. But the thing about Joe is, he knows how to look out there and how to act to make you think he’s doing what he’s doing.”

And Zawinul’s successor as pianist in Adderley’s band, George Duke, reminisced about the uncanny cross-over Zawinul was able to pull off: “I wanted to take Joe Zawinul and take it into a more ‘black’ experience. But actually, Joe had that as well, which is amazing considering where he came from. I don’t know where he got it, but he was as soulful as any black person I ever heard.”

Like their black journalist colleagues, these musicians use the key markers of “the blues” and “soul,” which are not simply stylistic traits but also a question of a deeper aesthetic practice, a virtue. My research shows that “soul,” “blues,” and other related terms are singled out as essential stylistic elements of Zawinul’s composition, improvisation, and performance, and I argue that these descriptors suggest his successful appropriation of and assimilation into African American culture—even if they also mark him as an exception in this regard. But they also go beyond essentialism because black journalists and musicians used them as examples of how such categories did not exclude Zawinul. The virtues of soul and blues were not out of reach for Zawinul, but something that he had assumed.

The black reception of Zawinul’s music shows us that tales of musical appropriation and assimilation are often more complicated than the politics of essential stylistic markers suggest on the surface. By contrast, Zawinul’s own self-image also shows us that African American writers and musicians were, perhaps, better attuned to the nuances of the appropriation of their music than a white guy from Austria was.

(In the rest of the chapter, Vad charts the development Zawinul’s autobiographical narrative in further detail. In a second part of the chapter, not recounted above, Vad also explores how Zawinul’s racial politics played out in the 1970s, as he became a major name in jazz as part of the fusion jazz band Weather Report.)