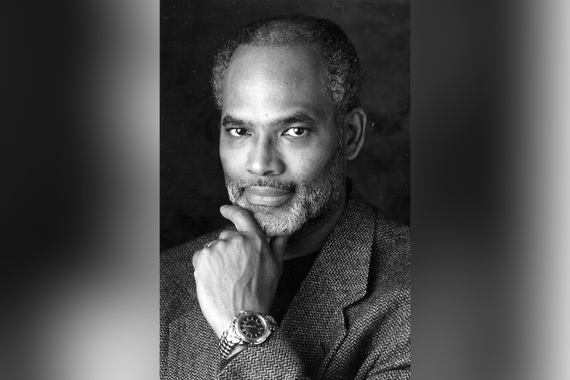

Arash Davari: Revolutions, Politics, and the Now

Born in Iran a few years after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Arash Davari believes that the event shaped a significant portion of his life and career path in political science.

“I’ve spent most of my life in environments and contexts where politics is present, even when it's not explicitly present. And the legacies of the revolution are present, even when they're not explicitly present.”

Davari joined the Department of Political Science this past fall and is excited to dig deeper into his research on the Iranian Revolution, teach classes in political theory, and get to know his new home state of Minnesota.

Why Political Science?

Like many people born in a post-revolutionary period, Davari experienced the world as a place sculpted by political dynamics and questions. “In order to make sense of my place in the world, I found it almost necessary to pursue some kind of activity where I could ask these questions in a deep fashion,” he says.

Pursuing a career in political science (with a focus on political theory) allowed Davari to dissect and analyze these questions. “It gave me an opportunity to really engage with history as it continues to live all around me in a deep and meaningful way,” he says.

Davari is particularly interested in questions of form, examining the ways in which things are presented in addition to their contents. Davari applies these questions of form and rhetoric to approach his research work.

Political theorists in the West generally focus on the American and French Revolutions, but there is a lack of sustained theoretical conversation about revolutions not part of the Western world. “One of my objectives,” says Davari, “is to have the 1979 revolution in Iran considered as offering something distinct and worthwhile for political theorists to consider when they talk about revolution and the impact it has on our daily political lives.”

Typically, political theorists draw a line between the 1979 revolution in Iran and ones that come after that (including the 1989 revolutions in Eastern Europe, the Arab uprisings that began in 2010-11, and even the recent uprising in Iran) because of the difference in their substance and themes. However, Davari’s approach is, once again, to pay attention to form.

“What if there are some fundamental, formal similarities between the way revolutions were waged before 1979 and in our present day?” Davari asks. “How does that alter how we assess and think about where we are now and how the past lives with us in the present?”

Engaging in this kind of work is a meaningful way for Davari to connect with his Iranian identity. Having grown up outside of Iran but also revisiting the country quite a bit over the years, Davari is interested in seeing how he can offer a perspective that is “neither here nor there.”

Present: At the University of Minnesota

Apart from having an academic home in which to conduct his research, Davari is excited to work at a top-tier university with a reputed political science department. He is particularly eager for the opportunities to collaborate with the political theory faculty and other social sciences departments.

During fall 2022, Davari taught the course on POL 3235W - Democracy and Citizenship. In this course, students study criticism of classical discussions of democracy and citizenship with respect to questions of race, class, and gender.

“The second half of the class puts this foundational material in conversation with current political debates. Is democracy eroding in the United States? Who counts as a citizen? What are the prospects for democracy and citizenship given digital technologies, modern day policing, incarceration, and climate change?”

This spring, he is teaching POL 3210 - Topics in Political Theory: Revolution, which aims to answer questions like “What is revolution in the twenty-first century? How did the idea that ‘revolutions are the start of something new’ come to be? Should we continue to endorse revolutions today?”

The course delves into debates at the intersection of history and theory and focuses on two major revolutions: the 1789 French Revolution and the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

For Davari, the most rewarding aspect of teaching is seeing the diverse range of perspectives that students bring to the classroom.

“I pose questions, and we have debates and think about concepts, issues, problems that are timely. To see students draw connections between that material and things that they've seen and experienced in their personal lives is energizing and exciting as a teacher,” says Davari.

Another five years down the line, Davari still sees himself at the University of Minnesota: teaching, publishing his first book, and engaging in more projects that raise timely questions about the political world.

This story was written by an undergraduate student in CLA