The Fate of the Fourth Estate

It’s hard to picture a healthy democracy without a healthy journalistic culture. Luckily, great journalism thrives—but so does misleading, false, and biased journalism.

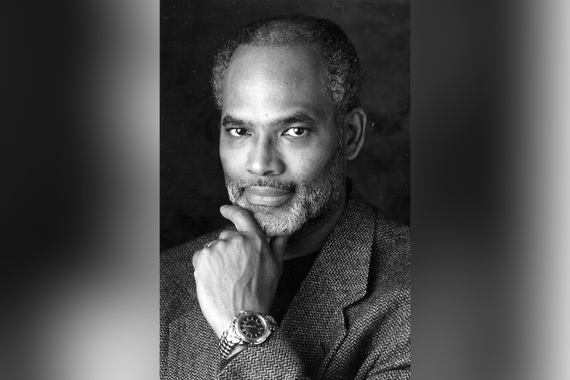

The work of journalism professor Ben Toff raises a troubling question: How much difference does good or bad journalism make if people don’t want to read, watch, or listen to it?

Among Toff’s recent research interests is a group he calls “news avoiders,” people who go out of their way to not pay attention, and others who don’t go out of their way but simply don’t consume much news. He’s headed to Iowa soon to study “news avoiders” there and compare notes with colleagues studying the same phenomenon in Britain and Spain.

The extreme “avoiders” are a relatively small group: between two and eight percent of the public, Toff estimates. Unsurprisingly, news avoiders are less likely to vote, and less likely able to describe their political views. Avoiders who do vote say they tend to base their vote on information from family members they trust, or from social media. Another type of modern news consumers are those who don’t use traditional forms of journalism, but simply surf the internet if they want to know about a particular current event. A much bigger group, roughly 38 percent of the US public, are not strictly news avoiders but say they don’t follow the news closely, Toff says. The reasons they give are similar to the extreme avoiders: current events are “too negative,” “frustrating,” “annoying.”

On the flip side, to those committed to being well informed, the current access to information is “amazing,” Toff says. He calls them a “community of news users,” and believes one factor prompting them to follow the news is the social benefit that flows from membership in that informal community. And news followers vote. It’s well established, for example, that newspaper readers vote at high rates, although newspaper readership is shrinking.

So how do these wide disparities in news consumption relate to the health of a society’s democracy? “If we’re fine with a smaller group of highly engaged people being the only ones that vote, that’s one thing,” Toff says. “But if want to live in a system where our democracy is responsive to the wide range of the public, whether they are particularly engaged, we need to worry about these trends.”

What about the “Fox-MSNBC effect,” a modern phenomenon where right-leaning viewers get their news from Fox News, with its lineup of conservative stars led by Sean Hannity, and liberals are more likely to tune in to Rachel Maddow on MSNBC? “It’s actually a small number of people that get most of their news from partisan media,” he says. “Most people don’t follow much news about politics generally. Pew studies show that most people who rely on TV for news get it from their local network stations, which are much less partisan. Most people are not that political, and most of the news they consume is not political news,” Toff adds.

“So the concern is not about average people…[but] about the highly engaged political class. Activists, politicians, the donor groups do fall into that category. Perhaps that makes those partisan sources more influential than you might think just based on the ratings, which aren’t that high. So it’s complicated to evaluate the impact of the Fox-MSNBC phenomenon.

“But I do have concerns about whether our news environment is all that conducive to creating an electorate of people who actually hear the other side, can think through complicated political debates and issues, and understand a variety of different perspectives.”