Students as Map Makers: Connecting Concepts to Geography

The phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words” is common for a reason; it is true that multiple ideas can be conveyed through a single image. That’s why the Department of Spanish & Portuguese Studies has started integrating a story mapping technology into its courses.

Bringing Story Maps to the Classroom

Story Maps are an online resource that integrates spatial thinking with storytelling to present information in a compelling, interactive, and easy-to-understand format. Simply put, the technology links culture to place.

Cecily Brown and Stephanie Anderson are instructors who have taken advantage of Story Maps. In their Spanish 1001-1002 classes, students do a project where they produce a written statement in Spanish, including short texts, specific locations, and images. Story Maps combine these assets to support and communicate the topics.

Brown gives credit to Shana Crosson from the Liberal Arts Technologies and Innovation Services (LATIS) for helping students plan their projects; Crosson provided templates that helped to shape assignments and evaluate the students' work. She says: “I see languages as a natural place where spatial thinking is especially relevant, so I was thrilled when Cecily approached me about doing this project.”

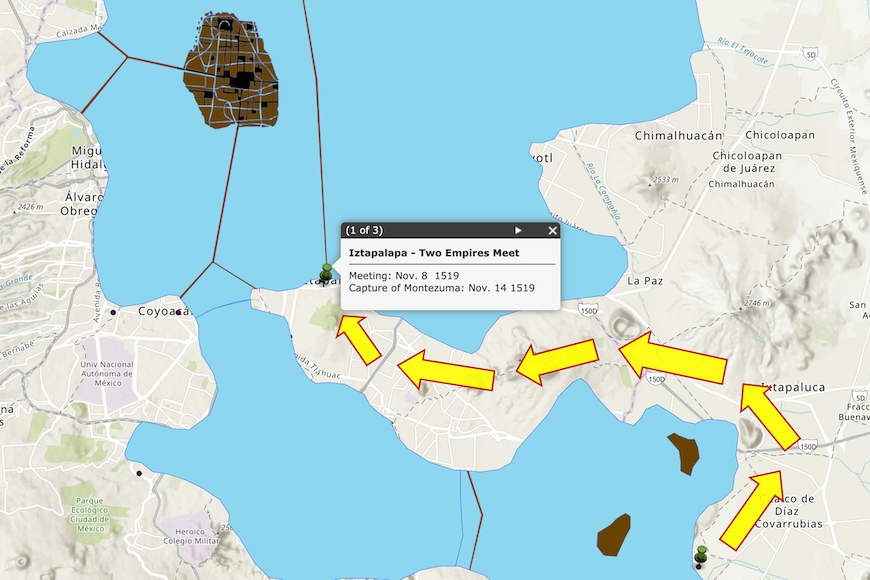

Sarah Chambers is another instructor who has received support from the LATIS staff. As a professor in the Department of History, she first started using the Story Maps application in 2016 for her Early Latin America to 1825 class. “The combination of text, images, and maps can really amplify the dimensions of teaching and learning about history,” she says.

Students As Map Makers

By combining their research with Story Maps, students cultivate a greater understanding of the subject material. “We see that when students become map makers, they discover content in a way that they do not when they are seeing a map already made,” Crosson explains.

Brown also notices a sense of ownership about the knowledge they are creating and sharing. Creating story maps is a way to enhance enthusiasm for those who enjoy a more visual learning experience.“These projects situated those cultural products and practices in their specific places in a way that was completely understandable to their classmates because of the maps,” says Brown.

“One student did a project on the spread of disease after Spanish incursions into the Americas during the 1500s,” Chambers explains. “She was able to address debates among scholars over how quickly viruses could spread and how to calculate demographic declines, but then she also demonstrated the process visually.”

At the end of the semester, small groups in Chambers’ class choose a figure from the course (e.g. one of the conquistadors or leaders of indigenous or slave rebellions) and search for monuments or sites named for that person. Students then share their maps and discuss the politics of historical memory.

Story Maps can be applied to a wide variety of courses. For example, a literature class could map the travels of Don Quixote, a linguistics class could map the indigenous languages of Mexico, and a history class could map political resistance movements.

Cultural Competency

One of the greatest takeaways from using Story Maps is the framework and structure it provides students to enhance cultural competency. Learning about how culture relates to physical geography and language is key to communicating and interacting with people across cultures.

In teaching Latin American history, one of Chambers’ goals is for students to become familiar with the geography of the continent, as well as the ways boundaries have shifted over the centuries. Colonialism, changes in trade, warfare among imperial states, and revolutions have all resulted in spatial transformations. “Story mapping is more effective at conveying these dynamic processes than simply reading and lecturing,” says Chambers.

Support for individual classes was made possible by the College of Liberal Arts Academic Innovation Grant, which supported the hiring of a graduate research assistant 50% for one term. Instructors plan to continue incorporating story mapping into their curriculum in the future. “Next year, I hope to create an ongoing, collaborative Story Map for Spanish 1001-1002 to map what students are learning about the cultures of the Spanish-speaking world as we study them,” says Brown.

This story was written by an undergraduate student in Backpack. Meet the team.