Of, Under, and Beyond This Earth: "what moves between" at Katherine E. Nash Gallery

Sometimes the hardest part of mounting an exhibition is coming up with the right name for it. Before the artwork is even hung, you have to decide what you’re going to call this thing — what word or phrase will shape the show in the viewer’s imagination and capture some of the magic you are about to put on display.

It’s even harder when there is not just one artist but seven, as in the MFA thesis exhibition now on view in the Katherine E. Nash Gallery. How do you sum up three years worth of work by seven different artists in one tidy phrase?

“When I was suggesting this title, I was thinking of how the phrase ‘what moves between’ was one that needed something before and after it to make sense,” explains Prerna, one of the artists in the show. “I was drawn to how it felt like it was in between a sentence, and held a myriad of meanings when used out of a sentence and out of context. It raised questions: what moves between…us?' How is our work connected?”

The answer to that emerges slowly but quite clearly in the gallery. What is striking is how well the name fits this collection of work and how much these artists’ installations seem to be in conversation with each other. A proper cohort: bound clearly by an interest in material, place, and transition.

From the start, you the viewer must literally move between the works, gingerly avoiding the ceramic sculptures on the floor, the dark pool of water, the tower of foam and fabric. As we explore each artist’s show-within-a-show (each with their own titles), we are offered a path between a great many binaries: between indoors and outdoors, between the physical and the digital, between life and death. The show moves between continents, families, generations, and — for these seven artists — ultimately between being students and being Masters, so to speak.

Earth and dirt loom large from the start, in Cody Hilleboe’s beautiful, desolate panoramic photos and rough, unglazed clay sculptures. Like fossils in a desert, the small brown and white ceramic shapes sit in front of the cinematic photographs as though part of the landscapes themselves — bits of forgotten furniture shaped with aggressive thumbprints or detached extrusions. There’s a sense of discovery to these objects and pictures, a tension between making and finding. One piece stands alone, its walls folded in on each other like rolls of flesh — a vessel squished, fired, and cracked at the edges, but still standing. A picture of resignation and resilience all at once. A Bleak Beauty, as Hilleboe names it.

Soil is not just a material, of course. It’s also a signifier of place; in Stephanie Lindquist’s case, seventeen very specific places across Minnesota and Sierra Leone. Combining digital photography, cyanotype, and social practice, Lindquist then paints over her images with mixtures of dirt, capturing the light, soil, and soul of a moment spent in community with friends and family or spent standing under a sunflower. An Archive of Earthy Intimacies explores that earthiness inside and out, diving microscopically into the bacteria and fungi that give a patch of soil its personality. From dust we come and to dust we shall return, they say, but apparently some forms of life stay there the whole time. It’s a reminder that the scale of both time and place on this Earth are nothing if not relative.

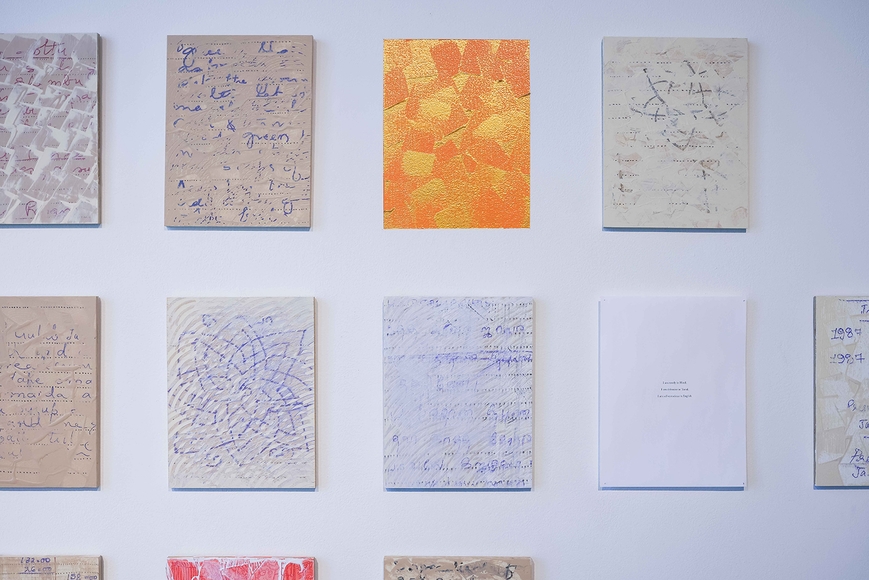

From the outside, Prerna then moves us indoors, to Unknown. The banality of building materials — glass block windows, pink insulation foam, laser-cut drywall — butts up against the handwritten details of a human life caught moving between cultures, languages, and domestic roles. Words fade in and out in the installation. The centerpiece is sturdy, architectural, but unreadable: a pink tower of repeating layers reaching from floor to ceiling, only showing us the shape of a word and never its face. On the wall, scraps of paper — notes, lists, doodles, and calculations — sink beneath material, capturing a personal history and obscuring it at the same time. We are left wondering after another person’s past, like walking through an empty house and finding traces of a life once lived.

Also balancing between inside and out, Hayden Teachout’s Degrees of Opacity is a rich, dark investigation of privacy, voyeurism, and grief. He confronts us first with an arresting image shot through with a sliver of light, catching a man’s naked body contorting on the ground, one hand reaching out towards us in a sort of helpless welcome. Nearby, another naked body lays prone, face-down on a lush forest floor, the pale skin in high contrast to the dark, mossy trunks around it. These are portraits that invite you to spend a moment and adjust your vision to take them in. Up close, an eye catches the light of a small fire, obscuring the sitter’s face and chest in near-total darkness. How much do we truly see of each other, and how much do we truly show?

“It makes sense that what moves between is possibly our most serious MFA thesis exhibition,” writes Professor Jenny Schmid, Director of Graduate Studies, “holding both the grief and care of the conditions that this cohort has been making art in.” A global pandemic that shut down so much, a local uprising that garnered global attention, and never-ending political turmoil, Schmid notes, all forcing this cohort to “deal with this new reality since the spring of their first year of the University of Minnesota’s three-year MFA program.”

Back in the gallery, a bit of brightness is in order perhaps, found in the white walls and flashes of color in Julia Maiuri’s Hollow, a collection of small paintings with big impact. That one tiny canvas can hold an entire wall is a testament to the skill with which they are painted. Maiuri offers up a different take on the cinematic, overlapping film stills to offer us fragments of narrative — tension, conflict, and no resolution. A hand reaching for a doorknob, a shadow standing over a bed, a key lying flat in someone’s palm — each scene cut through with another face or eye or hand, painted with a light touch, a muted vibrance, and a threat of violence. It’s a dread we all know too well, studied here at a distance that invites you closer, perhaps at your own peril.

Moving from a white room to one painted black, we find ourselves at the back of the gallery. Taylor Johnson offers us Dioramas in the Dark, dominated by a sculptural installation of not-quite-taxidermied creatures — flocked felt fictions somewhere between dogs and demons. They’re in turn sweet and stand-offish, a natural history museum approach to death and mythology that moves between this plane and another. In one of the most memorable moments of the show, an animated drawing of a fox is projected on top of a black and white lithograph of the animal dead on the forest floor. The white outlined spirit rises from its body and meanders across the paper and over onto the black wall itself. It looks about lazily before slowly vanishing, an eerie bit of sweetness that anyone who has lost an animal in their lives will recognize.

A good place to end is in Lela Pierce’s In the Company of Stars. Also painted in black, the walls here perfectly compliment the neon colors of Pierce’s wall-mounted sculptures and paintings. Imperfectly geometric, exuberantly esoteric, these shapes and colors vibrate off the walls, jutting out into space at sharp angles that recall both Ghanaian symbology and mathematical diagrams. Again, raw fired clay sits on the ground, here collecting powdered pigment — kumkuma, turmeric slaked with lime — as though dropped like an offering from the artworks above. Inside, you are invited to lay down and look up at a video. It begins with a burial — or an unearthing, it’s hard to say. The artist emerges from the soil, projected in duplicate: one dancing futuristically, a shaman in silver robes; another wiping away snow and peering down at us, as though we are trapped in ice behind the lens and they are trying to get us out. Or perhaps wake us up. A strong sense of the spiritual, the traditional, and the ritualistic in Pierce’s work invite you to leave the show looking backwards across time, culture, and lineage, and forward to something wholly unknown.

In this present moment, however, you only have through April 23rd to move between these works yourself, to soak in the material and conceptual results of work made during three years unlike any others in our own brief lifetimes. From dust to dust, as the adage goes. But not just yet.

what moves between is on view in the Katherine E. Nash Gallery through April 23, with a Reception + Public Program on Thursday, April 21, 6-8:30pm. Gallery hours and information available here. Masks are required in the gallery.

All photos by Easton M. Green.