Rwanda

-Immaculée Ilibagiza

Introduction

Beginning in 1994 and lasting only 100 days, the Rwandan Genocide is one of the most notorious modern genocides. During this 100 day period between April and July 1994, nearly one million ethnic Tutsi and moderate Hutu were killed as the international community and UN peacekeepers stood by.

To understand how such a tragic event could happen, the Rwandan Genocide must first be seen as the product of Belgian colonialism. It was during colonial rule that Rwanda’s ethnic groups: Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa became racialized. It was the rigidification of these identities and their relationship with political power that would lay the foundation for genocidal violence. When Rwanda gained independence in 1962, the ethnic majority, Hutus, were left in power. Hutu rule resulted in widespread discrimination against Tutsi, laying the groundwork for the 1994 genocide.

Additionally, the Rwandan Genocide must also be understood as taking place within the context of a civil war. Before the genocide began, a civil war began between the government’s armed forces and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), led by Tutsi exiles in Uganda broke out in 1990. The context of an ongoing war led to anti-Tutsi propaganda, painting Tutsis as dangerous traitors. In 1994, when the Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down, the genocide began, in which 800,000 Tutsi and many moderate Hutus were massacred. The violence caused a major humanitarian crisis that continues to affect the Great Lakes Region, and the international community’s failure to intervene and stop the violence continues to leave a stain on the reputation of UN Peacekeeping today.

For more information about and an overview of the Rwandan Genocide, check out:

- Read: The Order of Genocide: Race, Power, and War in Rwanda to learn about the role race and the civil war played in the genocide

- Read: “Background to Genocide: Rwanda”

- Read: Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda for an in-depth overview of the major events of the Rwandan Genocide

- Watch: A VERY Short History of Rwanda (great for classrooms!)

Major Actors

Perpetrators of Genocide: Belgium Colonizers, Hutus, and RTLM

In 1962, Rwanda gained independence from Belgium, but the roughly 30 years of Belgian rule left an indelible mark on the country and its people. While some argue Rwanda’s Hutu majority are Bantu people from the southwest, and the Tutsi are Nilotic people that migrated from the northeast, Gourevitch argues these theories are derived from racist legends. Rwandan history is largely undocumented, so explanations about the origins of these two groups and the differences between them, are widely speculative. While it is known that these ethnic identities preceded colonization, these identities, which were quite fluid in practice, became rigidified and racialized under Belgian colonial rule through the use of ID cards. The colonial period was largely characterized by the rule of the Tutsi elite and the exploitation of Hutu. But the 1959 Hutu Peasant Revolt resulted in the Belgians reallocating power to the Hutu majority.

With independence, the Hutus consolidated power and facilitated widespread discrimination against Tutsi, excluding Tutsis from prominent careers and implementing education quotas. A Hutu Power ideology emerged, grounded in the Hamitic Hypothesis, in which Tutsi were recognized as foreigners to Rwanda, rather than an indigenous ethnic group. This racist ideology, initially propagated by Germany and later Belgium during colonization, argued Tutsis were inferior to the Hutu majority. This theory would be used to incite the genocide in 1994. In the months and weeks before the genocide began, Hutu radicals began compiling lists of potential Tutsi targets and moderate Hutus. In addition, the Hutu dominated government began stockpiling weapons, including machetes. These machetes and other rudimentary weapons would be the tools that carried out the genocide.

In mid-1993, Hutu radicals launched their own radio channel, Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM). The channel would be used to incite hatred towards Tutsi by using propaganda and racist ideology, such as the Hutu Ten Commandments. On April 6, 1994, when the President’s plane was shot down, killing both the Rwandan and Burundian presidents, the radical Hutu radio channel announced the deaths, urging Hutus to “go to work” and attack the Tutsi population. The genocide had begun.

Victims of Genocide and Non-Genocidal Violence

To truly understand the Rwandan Genocide, one must move beyond the traditional binary of perpetrators and victims. Rwandans often transcended the categories of victim, perpetrator, bystander and rescuer– acting as a rescuer at one moment and a perpetrator another. Tutsi victim testimony discusses the importance of rescuers– Hutu men and women who risked their own lives to hide and save Tutsi men, women, and children. Tusti survivors discuss a multitude of survival strategies from playing dead to negotiating and buying their safety.

Furthermore, both Hutus and Tutsis were subjected to mass violence, torture, and rape during the genocide. Yet because the victims of the Rwandan Genocide, per the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, were targeted for their ethnic identity solely, the victims of the genocide were Tutsis. It is important to note, however, that Hutus and some Twa were also victims of non-genocidal violence.

For example, both Tutsi and Hutu women were the victims of sexual violence. Hutu propaganda, such as the Hutu Ten Commandments, portrayed Tutsi women as being sexually available. This appealed to the Hutu desire to create an ethnically Hutu-homogenous state. Rape of Tutsi women was systematic, and after the genocide subsided, an outbreak of HIV swept throughout Rwanda. Yet Hutu women also experienced violence from both their Hutu counterparts and members of the Tutsi-led RPF that was progressing through the country trying to end the genocide.

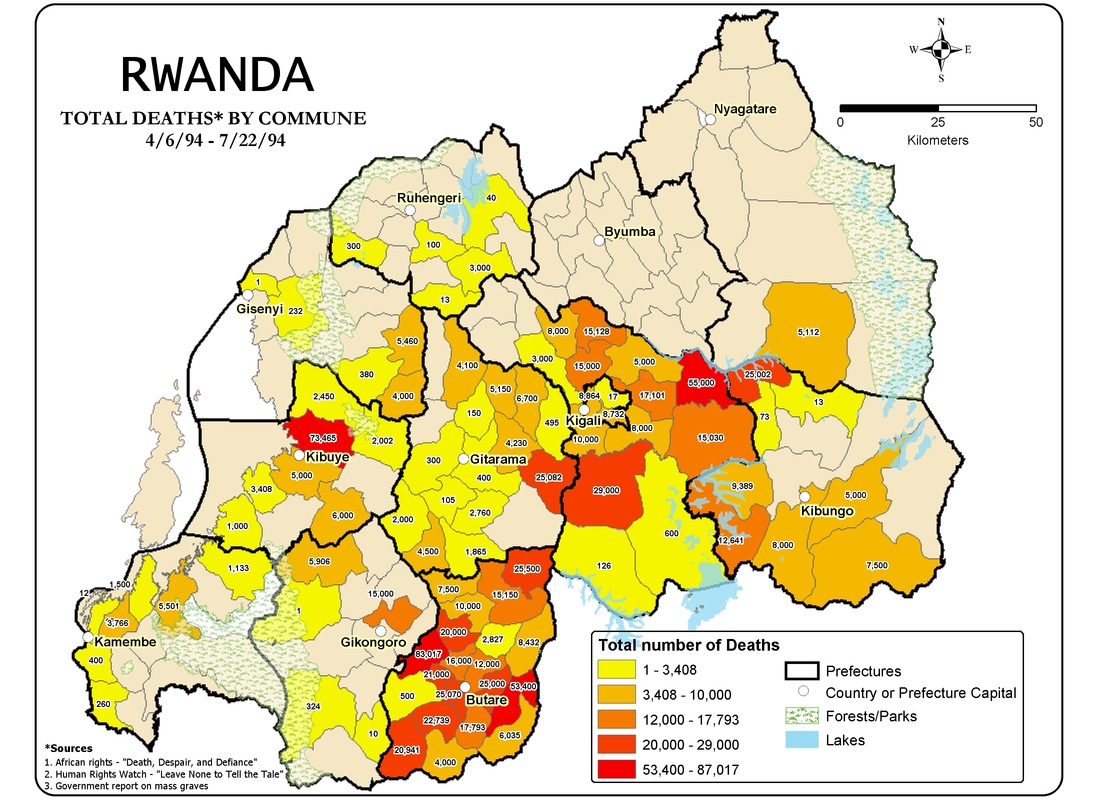

While genocidal violence was widespread throughout the country, some regions experienced more:

Survivor Testimony

- Voices of Rwanda is dedicated to recording and preserving testimonies of Rwandans, and to ensuring that their stories inform the world about genocide and inspire a global sense of responsibility to prevent human rights atrocities.

- USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education is now a repository for visual history from the genocide in Rwanda.

Watch Voices of Rwanda director, Taylor Krauss, discuss his work at the University of Minnesota in 2014 (Link: starts at 10:19)

** For more information about the major actors, check out:

- Read: Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust to learn about a Tutsi woman’s experience surviving the genocide

- Read: Surviving the Slaughter: The Ordeal of a Rwandan Refugee in Zaire to learn about a Hutu woman’s experience escaping violence committed by the RPF

- Read: When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda for an in-depth history of how the genocide came to be

- Read: “Toward a Dynamic Theory of Action at the Micro Level of Genocide: Killing, Distance, and Saving in 1994 Rwanda” to understand how and why Rwandans switched between the labels of perpetrators, bystanders, and rescuers

- Watch: Ubumuntu: Stories of Rescue during the Genocide in Rwanda

- Listen to: Genocide Archive of Rwanda for a database of RTLM radio broadcasts from July 8, 1993 to July 31, 1994

Major Events

1959 Hutu Peasant Revolt, or the Social Revolution

In November 1959, a Hutu uprising killed many Tutsi and caused 330,000 to seek refuge outside Rwanda. The Social Revolution, also known as the Hutu Peasant Revolt, lasted until 1961 and signified the end of Tutsi rule. This defining moment marked the beginning of Hutu power and directly preceded Rwanda’s independence from Belgium.

1990 Civil War Begins

On October 1, 1990, the Tutsi-led RPF launched its attack on Rwanda from Uganda, beginning the civil war. These attacks displaced thousands of Rwandans causing great insecurity and fear. This fear was used to construct all Tutsis, regardless of their affiliation with the RPF, as enemies of the state. Moderate Hutus who did not agree with the government’s extremist policies were also painted as traitors. It was during this time that ethnic stratification was exacerbated and Hutu ideology strengthened and disseminated.

1993 Arusha Accords and Creation of UNAMIR

In August 1993, RPF officials and President Habyarimana signed a ceasefire and power-sharing agreement known as the Arusha Peace Accords. The Arusha Accords was supposed to end the three-year-long civil war, integrate Tutsi exiles into Rwandan society, and democratize the Rwandan government.

With the passage of the Arusha Accords, the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) was created. In January 1994, just weeks after arriving in Rwanda, the UN Commander, Candian General Romeo Dallaire, sent a memo to the UN Security Council warning about the stockpile of weapons and an increase in violence between the Hutus and Tutsis. The warning went unheeded.

Despite warnings from the UNAMIR commander, no relief was sent to the country. In addition, the use of Belgian troops for the UN mission violated UN regulations banning colonial powers from providing troops to missions in former colonies. Once the genocide began, European powers sent troops in to pull out their citizens, but they did not provide relief for UNAMIR or assist in helping end the violence. In several cases, there are reports of UN peacekeeping troops acting as bystanders as Hutus massacred Tutsis in churches or in the streets.

April 6, 1994 Plane Crash

On April 6, an airplane carrying both Juvénal Habyarimana, the President of Rwanda, and Cyprien Ntaryamira, the President of Burundi was shot down. Both presidents were Hutu and were killed. The assassination was blamed on the Tutsi minority and immediately resulted in the use of roadblocks throughout the country and sparked the genocide. To this day, there is no conclusive evidence regarding who shot down the plane, but theories range from moderate Hutus to the Tutsi-led RPF

July 15, 1994 Genocide Ends

Although the genocide’s timeline is considered to be April 7–July 15, the majority of the killings occurred within the first six weeks. An estimated 800,000 people were killed by mid-May, and the accelerated pace of the killings outpaced the Holocaust. The rate of death in the Rwandan Genocide is also noteworthy because of the lack of centrality accompanying it. Unlike the efficiency seen in the Holocaust or Cambodian Genocide, the killings in Rwanda were more reliant on individuals acting out orders from a central command and the use of rudimentary weapons. This often meant victims knew their attackers personally.

After mid-May, the killings began to slow. The RPF gradually took back significant parts of the country, and by July, the RPF pushed the sitting government out of the country and the genocide finally came to an end. Today, the 4th of July is a holiday that commemorates the end of the Rwandan Genocide against Tutsi.

** For more information about the major events and role of UNAMIR, check out:

- Read: Rwanda: A Brief History of the Country for a timeline of the major events

- Read: Rwanda: The Failure of the Arusha Accords to learn about the failure of the international community and the Arusha Accords

- Read: The US and the Genocide in Rwanda 1994: Evidence of Inaction to learn about the failure of the US to interveneWatch: Shake Hands with the Devil: The Journey of Roméo Dallaire

Curt Goering, Former Chief Operating Officer of Amnesty International, discussed the failure of Amnesty International to respond to the Rwandan genocide from a conference at the University of Minnesota in 2014 (Link: starts at 26:25)

Legacy

Justice and Accountability: The ICTR and Gacaca

Bringing justice to those responsible for the genocide was enormously difficult in Rwanda. More than two-thirds of the judges in Rwanda had fled the country or were killed. With only a third of judges still practicing in the country and prisons at 200% capacity, the Rwandan justice system was overwhelmed. In an effort to address these challenges and foster an atmosphere of justice and accountability, two main justice mechanisms were constructed: the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) set up by the UN and Rwanda’s own community-driven Gacaca courts.

The ICTR was created to prosecute high-level offenders and thus focused its efforts on prosecuting the main organizers of the genocide. The ICTR indicted 93 individuals, sentencing 62. This includes an interim Prime Minister of Rwanda and two men who ran the propaganda radio station, RTLM. Perhaps most notably, the ICTR is the first tribunal to interpret the definition of genocide, as set forth in the 1948 Geneva Conventions, and it is the first conceptualize rape as a method of genocide.

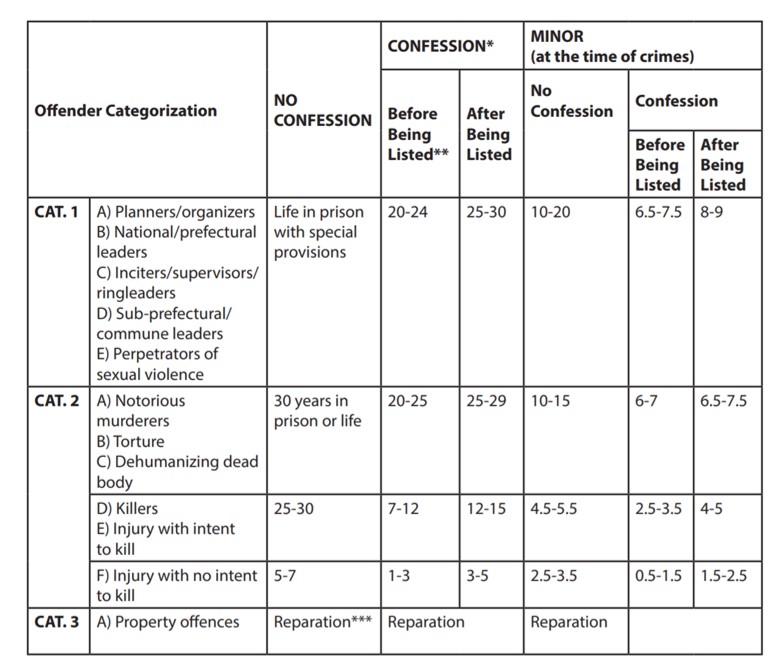

Alternatively, Gacaca courts sought to prosecute lower-level perpetrators. Attendance was mandatory for all Rwandans, as communities came together to bear witness to the telling of crimes. Just under two million cases were heard at the Gacaca courts, with many people found guilty facing punishments from monetary payments to jail time. Most notably, accused perpetrators were given less time in exchange for their confessions, as seen in the chart below.

Chart from Hola & Brehm (2016)

High School Social Studies Lesson Plan: Collective Responsibility & the International Community in the Rwandan Genocide: “The Blame Game”

Commemoration

Today, the genocide is commemorated annually in Rwanda in various Kwibuka (to remember in Kinyarwanda) ceremonies. There are many memorial sites in Rwanda, but the most visited is the Kigali Genocide Memorial which serves as a burial site for 250,000 Tutsi victims. Each year, Rwandans remember the genocide through lectures, reenactments, music, and vigils.

Today, discussion of ethnicity is regulated in the public sphere. Ethnic identities such as Hutu and Tutsi have been made illegal, but the association of Hutu with perpetrators and Tutsi with victims continues to affect social interactions between individuals. In Rwanda, there are both stories of perpetrators being welcomed home by their communities (including survivors), but there are also stories of individuals who refuse to engage in inter-ethnic marriages.

Jean-Damascene Gasanabo, Director General of the National Research and Documentation Center on Genocide at Rwanda's National Commission for the Fight Against Genocide spoke about commemoration and materialization at the University of Minnesota in 2014 (Link: starts at 27:28)

** For more information about transitional justice and commemoration following the Rwandan Genocide, check out:

- Read: Rwanda’s Justice System to learn about the various justice mechanisms and key perpetrators

- Read: Gacaca Justice System: Rwanda Quest for Justice in the post Genocide Era to learn more about the use of Gacaca

- Read: “Genocide, Justice, and Rwanda’s Gacaca Courts” for an in-depth assessment of Gacaca

- Read: “Music and the Politics of the Past: Kizito Mihigo’s Story and Music in the Commemoration of the Genocide against Tutsi in Rwanda” to learn about commemoration

- Read: Negotiating Genocide in Rwanda: The Politics of History to learn how Rwandans make sense of the genocide

- Visit: Kwibuka to learn more about Rwanda’s annual commemoration

Hollie Nyseth Brehm and Chris Uggen discussed the Gacaca court system from a conference at the U of MN in 2014 (Link: starts at 24:00)

Connection to Minnesota

Throughout and following the genocide, many refugees fled Rwanda and were repatriated. The majority of refugees were relocated to countries like Belgium, Burundi, Kenya, and Uganda. Only a small amount (about 7,000) were relocated to the US. While it is unclear how many Rwandans were repatriated in Minnesota, since 2013, Minnesota has designated April 7 as Rwandan Genocide Remembrance Day, and more generally, it has named the month of April as Genocide Awareness and Prevention Month.