Preserving Activism: Inside the Minnesota Human Rights Archive

This past February, the Minnesota Human Rights Archive (MHRA) launched its first exhibition, “Global Reach of Local Activism: Minnesota Human Rights Stories,” which documents the history of human rights activism in Minnesota. I had the opportunity to speak with Erik Moore and Kris Kiesling, two University archivists who have been working on the project since its inception, to learn more about the MHRA project, what makes it unique, and the value and importance of archives.

History of the Minnesota Human Rights Archive

In 2016, staff and faculty at the University of Minnesota began conversations about collecting items to build a human rights archive. Barbara Frey, former director of the Human Rights Program, and Kris Kiesling, director of the Archives and Special Collections (ASC), met with others around the University to discuss the possibilities of bringing in archival materials from organizations around the Twin Cities as an initial step toward building an international human rights collection.

David Weissbrodt, a professor at University of Minnesota Law School and world renowned scholar of international human rights, had a large collection of materials on the third floor of the law school library that needed a permanent home. Professor Weissbrodt, who founded and directed the Human Rights Center, was also an early adopter of online collections, supporting an internet-based human rights library that was a critical resource for scholars and activists. He quickly offered up materials from the HRC and his personal collection to the archive. The Weissbrodt collections were key to the creation of a unique human rights archive based at ASC.

Frey, a longtime leader in Minnesota’s human rights community, and Kiesling agreed upon the importance of building an international human rights collection at the University. With the support of the Ohanessian Dialogues fund of the Minneapolis Foundation, Frey engaged then-PhD candidate Meyer Weinshel to carry out a feasibility study for the archives project in 2021. Frey and Kiesling invited colleagues at the Human Rights Center, the Roy Wilkins Center, and the Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies to donate selected materials to the collection. A Human Rights Initiative grant in 2021 provided critical seed money to begin more serious collections from key organizations, such as the Advocates for Human Rights and the Center for Victims of Torture, as well as scholars and activists across the region.

The human rights archives team grew quickly. University Archivist Erik Moore and Social Welfare History Archivist, Linnea Anderson, lent their expertise to support student researchers, follow up on potential human rights donors and cross-reference materials already in their collections. Patrick Finnegan, who served as a research assistant to Professor Weissbrodt for many years and organized his archival papers, helped coordinate all the moving pieces of the collaboration, from NGO relations to grant writing. Then-HRP coordinator and interim director Rochelle Hammer provided an additional steady hand, managing students, budgets, and grants.

Overview of the MHRA

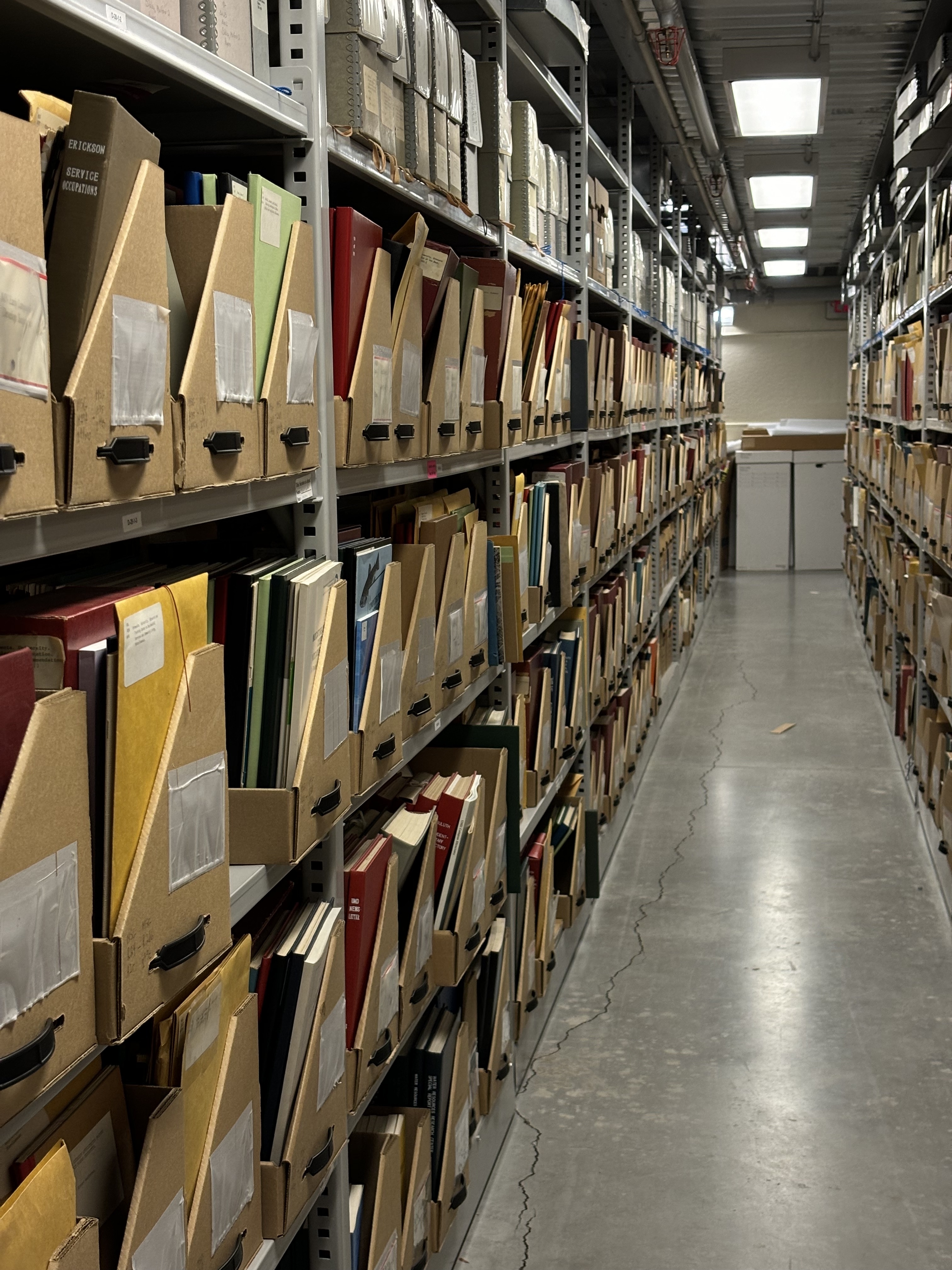

Prior to this organized effort, the ASC already held a significant amount of material related to human rights, including materials from the Minnesota Coalition for Battered Women. “We have a lot of collections that reflect [various human rights violations] here in the archives. It’s hard to think about history without thinking about human rights,” said Kiesling. But the Minnesota Human Rights Archive (MHRA) is different from most of the collections at ASC.

Unlike some of the other collecting units, it is thought of more as an umbrella collection. While the project has allowed the ASC to bring in materials from partners across the state of Minnesota, many of the materials in the MHRA are from related collections that pre-dated this project, like the Social Welfare History Archives and the Tretter Collection in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies. “The MHRA is not a new unit, it's not a separate collecting area,” Kiesling explained. “It's more of saying, ‘Here are these multiple collecting areas that all have content that is related to human rights.’”

The process of collecting new materials has also allowed staff at the ASC to begin revisiting collections that already exist, but through a human rights lens, which gives these materials new value. “Rather than being a distinct collecting unit, the MHRA is more of a framework of thinking about human rights and archival materials that can be found throughout all of the different archives and special collections here at Andersen Library,” notes Moore.

Although this project has been ongoing, it does not yet have a dedicated archivist to oversee the process. While this has made some aspects of the project more challenging, it has also emphasized the collaborative nature of the project. Building the MHRA has required numerous discussions with others working across areas of the ASC, University of Minnesota, and Twin Cities community at large.

A One-of-a-Kind Archive

Moore mentioned that human rights collections exist at other universities. What makes the MHRA unique, though, is the way that it engages with MN actors and organizations to paint a global picture of human rights. The history of human rights scholarship, advocacy, and activism has had a focal point in the upper Midwest. Many people know Minnesota because of its leadership on a wide range of international issues and stages, yet people in Minnesota may be less familiar with this work.

Kiesling emphasized that “Archives are all about preserving stories. We’re really looking to preserve those stories about individual participation in human rights and organization efforts in human rights, but this project is unique in that all of these stories are generated from Minnesota.” Being able to teach the local community about the significance of its history is a significant goal for the MHRA.

While the MHRA has incredible historical value, as it provides documentation on decisions or developments of human rights policies, it is also a place for people to use the materials in a way that was not originally foreseen. Now, people can create narratives that stretch across collections and issues to paint a broader history of human rights.

Moore and Kielsing spoke about their ongoing conversations about increasing the accessibility of these materials. The MHRA is open for anyone to use, regardless of one’s affiliation with the University of Minnesota. They emphasized how important it is that these materials not just be preserved in Andersen, but that they are used.

Eventually, archivists can begin to work with students and faculty to incorporate these collections into course curriculums and student projects, and “students can start to see the impact that those in Minnesota have had on the international stage,” says Moore. Apart from scholarship and research, the human rights stories housed in the MHRA can be used to inform policy decisions and the work of human rights organizations and individuals.

As the MHRA continues to grow, materials will be collected from organizations and individuals across the state, expanding the size of the collection and strengthening the impact of Minnesota on global human rights activism by acting as a central location for scholarship and research. New materials will be added to the ASC’s database and will become available to the public in the future.