Professor August Nimtz's Tribute to Mulford Q. Sibley

First, I want to thank Professor and Chair Paul Goren, Alexis, Kyle and other staff members for making it possible for us to be here this evening. When we had to cancel the event two years ago owing to the pandemic lockdown, it was not certain that we could ever do it. Paul persisted and we’re all thankful.

In the meantime, the University went ahead, as requested by our department, to name the space in front of the Social Science Building here on the West Bank campus Mulford Q. Sibley Plaza. Mulford’s embrace of a verdant environment is the reason for the naming. Anyone who can remember the barren concrete and brick appearance of that now all-so green oasis on the West Bank will appreciate his suggestion a half century ago that trees be rooted there. It was Mulford, a member of the political science department from 1948 to 1982, an internationally renowned scholar, who first proposed the trees and benches that now grace the space.

But Mulford is better known to an older generation of Minnesotans for another reason and all so relevant to the political moment in which we live today. Mulford, as far as I can determine, did more than anyone in the history of the University of Minnesota to successfully defend the right of free speech—the reason for this event. Four decades earlier another member of the political science department, William Schaper, lost that fight in the midst of the patriotic hysteria that accompanied World War I.

A new patriotic hysteria emerged after World War II—sometimes known as the Cold War. Its apogee was in October 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis or what the Cubans call the October Crisis, the closest the world has ever come to a nuclear war. Anti-Communism was rampant. Looking for a “communist” under every sheet or in every closet was the duty of every “loyal American,” we were told.

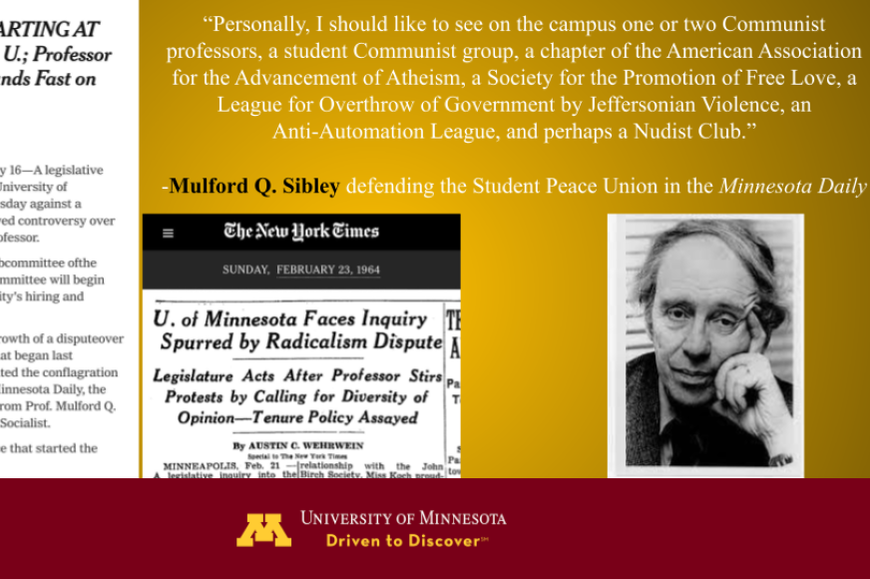

Into this heady mix stepped Mulford. Unsatisfied with an editorial in the Minnesota Daily, the student newspaper, which failed, in his opinion, to stand up forthrightly against the communist hunters, Mulford penned his fateful letter to the paper in fall 1963, exactly a year after the Missile Crisis. Boldly and intentionally provocative he wrote:

“I would like to see one or two communist professors on the faculty, plus a Student Communist Club, the American Association for the Advancement of Atheism, a Society for the Promotion of Free Love, a League for the Overthrow of Government by Jeffersonian Violence, an Anti-Automation League, and, perhaps, a Nudist Club. “We need students who challenge orthodoxies. Planting seeds of doubt and subversion help create moral and intellectual progress.”

Mulford Q. Sibley

As you can imagine, it--the word I can’t say here—hit the fan! Time doesn’t permit me to supply the details. But Mulford’s letter provoked a fight with right wing forces locally and nationally that lasted for almost two years, eventually reaching the State Capitol—and reported on by the New York Times in 1964.

Just as importantly, but not well known, Mulford’s colleagues defended him, individuals who didn’t necessarily agree with his opinions. Their solidarity was crucial in the inability of the “communist” hunters in getting him fired—unlike what happened with Schaper four decades earlier. The support of co-workers, wherever we are employed—the important lesson—is indispensable in defending civil liberties.

Mulford stood in the noble tradition of defenders of free speech going back to the Abolitionists before the Civil War. For anyone today, especially the youth, dissatisfied with the status quo, with the power hierarchy in place, having the right to defend their ideas in opposition to ruling elites is also indispensable. This is why the slave owners were such staunch opponents of free speech.

Frederick Douglass, the leading Black abolitionist, understood the issue better than anyone. His comment before the Civil War about opponents of free speech on both sides of the slavery question is most instructive:

It is “idle and short-sighted” to think only Black people will be targets of this anti-free speech campaign. “If, today, these parties can put down the right of speech on one subject, tomorrow they may do so on another. If they can prohibit the discussion of the rights of black men, they may also, bye and bye, prohibit the discussion of the rights of white men."

To oppose free speech was to be not just on the side of the slave owners. To do so could also be dangerous to the anti-slavery cause. It could come back to haunt sincere opponents of slavery by giving an excuse to their opponents to shut down the political space to disseminate their ideas. Again, “if, today, these parties can put down the right of speech on one subject, tomorrow they may do so on another.”

We’re doing this event in order to know the history and wisdom I’ve just distilled. When I came on board to be a member of the department, exactly fifty years ago, I didn’t know Mulford’s story—one that I should have known. Mulford made it possible for someone like me with my politics to be hired and, most importantly, to be tenured. When he wrote that he’d like to see one or two communist faculty members, little did he know that he’d might actually get one.

Our effort here tonight is to make sure that story is known so that future department members and, most importantly, our students know about it. It’s a proud history that we should make available to the broader public—whatever their politics.

I’ll end with a note I got a week ago from retired colleague Ed Fogelman, who collaborated with Mulford more closely and longer than I did.

"Academics have a special responsibility for exposing lies and dispelling ignorance. In every professional discipline, it is what we are, or should be, trained and expected to do. It is entailed in our commitment to seek the truth, whether in physics or philosophy; it is embedded in our claim to academic freedom. No one better exemplified this responsibility than Mulford. In both the classroom and the public world, he was outspoken in exposing lies and dispelling ignorance. He spoke out publicly on some of the most contentious issues of his time, including war and social injustice. He was denounced for some of his views – including for views he never held – but he kept his faith in free speech as a bulwark of democracy. He remains an example to us all."

Professor Emeritus Ed Fogelman

I wholeheartedly agree.