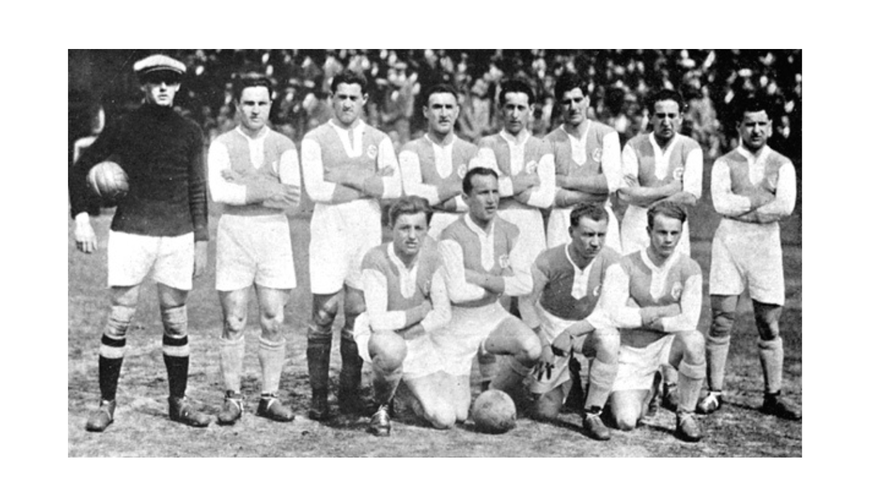

West Ham 0-5 Hakoah Vienna: How an All-Jewish Team Defeated the English at their own Game, Conquered Austrian Soccer, and Defied the Nazis

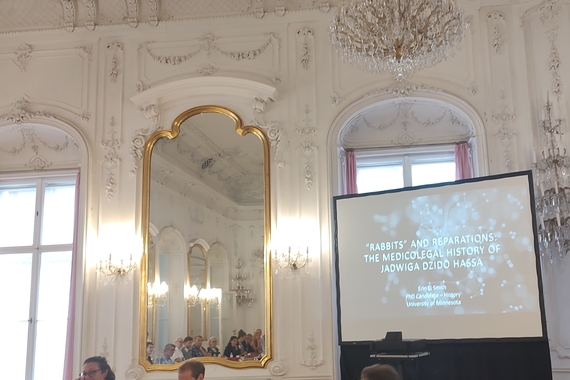

In March 2023, Professor Michael Lower (Morse Alumni Distinguished University Teaching Professor of History at the University of Minnesota) gave a lecture at the St. Paul JCC as part of the Center for Jewish Studies community lecture series. The title of the talk: “West Ham United 0-5 Hakoah Vienna: How an All-Jewish Team Defeated the English at Their Own Game, Conquered Austrian Soccer, and Defied the Nazis.” Prior to the event, Professor Lower spoke with Meyer Weinshel (CAS Staff Member and affiliate with the UMN Center for Jewish Studies; as of Fall 2023 Assistant Director of the Center for Austrian Studies) to discuss the project in greater depth.

This interview was originally published in the Center's 2022-23 Annual Report, and has been edited for length and clarity.

MW: Thank you for taking the time to meet with me at the Center for Austrian Studies. Let me start by asking: What initially drew you to this particular subject?

ML: When I was in graduate school in England I fell in love with soccer (or football as they call it). I became obsessed with the game, and even when I was back in Minnesota I was still obsessed with it. I began reading books about soccer all of the time. At some point, I decided that it would make sense to try to do something more productive with this information, so I created a class called “Soccer: Around the World with the Beautiful Game.” I taught the class for many years but always had a very strong personal and academic interest in Jewish history. It was out of these interests that I discovered Hakoah, an all-Jewish soccer team that played in Vienna in the 1920s. They not only played but really excelled and became champions of Austria. They went to England and beat one of the best English teams. They toured all over the world. I was fascinated by them and how they accomplished what they did. I was particularly interested in how Jewish sports fit into the wider currents of Jewish history, identity, and the early history of Zionism. I went down the rabbit hole and I haven’t come out yet.

MW: Do you see this project as being a departure from your previous works?

ML: My areas of scholarly expertise are the Middle Ages, Mediterranean history, and the history of the Crusades. This topic focuses on the Interwar Period, 1918-1945, so it is certainly a departure chronologically. It is a departure geographically, too. I have really focused on the Mediterranean, Near East, and North Africa, so it was a significant shift. I find that this shift also came out of teaching my soccer class and the larger connections the course was making. However, one thing I’ve always been interested in is the history of religious difference, how that difference is identified and constructed, and how it is contested amongst various groups that made up the medieval world. But of course, I took this interest into a modern register by studying athletes who were invested in distinguishing themselves as what they called “self-aware Jews.”

MW: On the topic of religious difference, how did Hakoah’s emergence reflect questions of religious difference (and Jewish politics) in Vienna?

ML: Hakoah’s ideology came out of Max Nordau’s famous speech to the Second Zionist Congress in 1898 about Muskeljudentum (“Muscular Judaism”). He borrowed this from “Muscular Christianity,” which came out of England and its imperial projects. Muscular Christianity was all about training the future rulers of a world empire. Muscular Judaism was about raising a generation of Jewish youth that would be needed for the Zionist project of creating a national homeland in Palestine. As such, Nordau also thought about sports as a kind of military preparation. The development of Hakoah also occurred simultaneously with the development of the gymnastics movement in Germany, which had a very militaristic orientation. Hakoah’s leading figures looked to the streets of Vienna and to kids playing soccer. They thought that this would be the best way to get people into the club and the Zionist idea. And that’s their focus, to latch onto football (soccer) and use it as a vehicle for proselytizing their particular point of view.

Obviously, the Zionists are defining themselves against the Christian majority. But, of course, this process of differentiation works internally as well because if you look at the Jewish population in Vienna between the wars, most people were assimilating. They were focused on becoming good Austrians. The Zionists at the time had a totally different conception of who they were. The Hakoah leadership was scathing about assimilation. When interviewed years later, once Hakoah had become a big success, Hakoah leaders would be asked the greatest challenge they faced when building up the club. They would say Nazis and “assimilationists.” By putting them in the same sentence, one can see how strongly they felt about it.

MW: Thinking more broadly about the demographics and political diversity of the Jewish population in the Austro-Hungarian empire, what was the makeup of this club? Were most of the members German-speaking? Were they from all parts of Austria and beyond? This leads me to another question about the name of the club itself. Was there a greater, more proactive Hebrew element to the club?

ML: Let’s begin with the demographics question. It worked on two levels: the actual players and the fans. What is really interesting is that the club as a whole (not just the soccer team) drew on a wider geographical area than other clubs at the time. Since Hakoah were limited by the ethno-religious aspect of the club, they needed to expand geographically. Teams in Hakoah had a very significant Hungarian element. This diversity did often lead to other teams othering them, saying that “they’re the Viennese champions, but really they are all just a bunch of Hungarians.”

Some of the players also came from Prague. The large number of members made it the biggest Jewish sports club in the world, but also the biggest Austrian sports club of any kind. It was enormous. There was also a lot of mobility and visibility of certain members, who became famous in their own right outside of athletics. One of them was Friedrich Torberg, the great Austrian writer. He was based in Prague originally, but moved around during his journalism career. Torberg played on the Hakoah water polo team.

Unfortunately, we do not have the kind of demographic information that we would like to have about these 2,500 to 3,000 members. What we do know is that some members of the club joined because of Zionism, while others just wanted to play sports. I mean, some joined because Hakoah had a ski hut in the Alps. There were a lot of folks like that. Others were serious professional athletes, like the footballers.

Now to answer your question regarding language, the club was relentlessly German but reflects geographic shifts of the 20th century. I have never seen anything from the time period related to the club in Hebrew or Yiddish. The club was suppressed by the Nazis in 1938, and the Holocaust scattered the surviving club members.

MW: The longevity of the club’s network is amazing, and it reflects other German Jewish emigre networks in the postwar period.

ML: Yes, it's amazing. There are actually copies of the newsletters in the Jewish Museum in Vienna, and it is important to note that they were written in German into the 1970s. It is remarkable that after living in a country that had made an incredible effort to make Hebrew the official language, they were writing this newsletter in German. Even after moving to the United States, Hakoah alums would contribute to the newsletter in German.

MW: Where have you done your research for this project?

ML: Circumstances have made it tough, but the one significant research trip that I’ve made was to the Jewish Museum in Vienna. They do not have a lot of written resources other than the newsletters I mentioned earlier, and unfortunately, the newsletters do not provide much information. Emigration proceeded very rapidly after 1938 (with the Nazis’ annexation of Austria into the German Reich). Ignaz Hermann Körner, the founder of the club, was actually one of the Jewish community leaders who had to work with the Nazis on emigration, and he was able to flee to Mandate Palestine. When you are leaving a country so quickly, you only take what you can carry, so what was left behind, now at the Jewish Museum of Vienna, is a lot of photos. They are very poignant. A lot of the images had labels and dates, but quite a few did not, so some guesswork is required. I had to figure out who was in them, where they were, when it was taken, etc. The club is beautifully documented in pictures.

The other major place where club records survive is in Ramat Gan (a suburb of Tel Aviv). That is the location of the Jewish Sports Museum, and the museum has an archive. In that archive, they have a couple of memoirs that some of the leading figures of the club wrote, and I am looking forward to digging into that. They also have the club’s famous “golden book.” The book was put together by some club members who had worked in the cartography office of the Austro-Hungarian army during the First World War. They would spend their days drawing maps for the army, but at night would work on compiling this memorial book for the club, so I am very eager to see that. They also have some trophies that were hauled to Tel Aviv from Vienna.

MW: The material aspect of the project itself is such a fascinating element to this story; you mention these photographs, trophies, “memorial” books compiled by former members, etc. In addition, it is very interesting how (post 1938) the memory of the club was salvaged and transplanted to other parts of the world. This was after the club’s golden years, when it traveled around the world, leaving memories, mementos, etc. behind on those trips, also. When Hakoah went to New York, for example, what was its reception and legacy?

ML: This is an important question, but it’s also important to mention why they traveled to begin with before 1938. The team operated at a financial loss. There really was only one way for the team to get media coverage (through the newspapers), but these weren’t ways to make money. The team would get publicity, but the only way money could be made was charging admission to see a match. However, during this time, it was still a mainly working class crowd; there were no luxury suites to sell. So, to pay the bills, they had to go out on the road for friendly matches. They were very popular; they had constituencies everywhere because they were a Jewish team and they were winning. They also felt that this whole model was an advertisement for Zionism and what Jews could accomplish if they united. Zionists around the world wanted to hear that message, so when they went on tour, they were often hosted by local Zionist committees.

That was the case for their American tour. In 1926 they went to America and played twelve matches. They organized workshops, hosted talks, all for Zionism. When they were in New York they played in front of 46,000 fans at the old Polo Grounds stadium in Manhattan. It was the most widely attended soccer game in the United States until the 1970s. Körner was actually received at the White House by President Calvin Coolidge.

While the American tour was probably the one that loomed largest, the second major trip overseas included Mandate Palestine and Egypt. Meir Dizengoff (the first mayor of Tel Aviv) was one of the

driving forces behind the coming of Hakoah, and was obsessed with the visit; it was one of the first times that European Jews visited Palestine for tourism. Dizengoff’s thought was that this tour would bring in money and help reorient urban development in the city. He also wanted to draw European Jews to Mandate Palestine. One of the players wrote a letter in which he predicted that this visit was going to be the beginning of a new era of wonderful relations between Arabs and Jews in the Middle East. This gives us a sense of the optics surrounding the tour.

MW: The team’s travel provides an excellent glimpse into the geographical and political scope of Jewish culture at the time—from North America to Palestine, and everywhere in between. Hakoah is also just one sliver of Jewish political, social, and cultural movements developing at the time

ML: Definitely! What picture of Jewish life between the wars can we get from studying Hakoah that we might not get otherwise? When you think of Vienna in this era, you tend to think about high German Jewish culture and modernism. You think about atonality (i.e., Arnold Schoenberg), psychoanalysis (i.e., Sigmund Freud), cafe culture, and the stereotypical “city Jew.” Of course, all this is going on, but there is this whole other side to Jewish life that is vital as well. However, the Holocaust obliterated this vibrant sports culture from our historical memory. The mass cultural phenomena of Jewish sports is largely forgotten. My hope is to recover this lost history by telling the story of Hakoah.

MW: We also tend to fixate on the horrific, traumatic, and “big” moments of Jewish history, but there were these smaller historical changes that had been happening throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The historical record is much more nuanced than it appears.

ML: One fascinating dimension of Hakoah’s story is that the vast majority of its members actually survived the Holocaust. Among the twenty players on the great Hakoah team that won the Austrian championship in 1924, all but one survived the Holocaust. Club histories list thirty-seven Hakoah members overall who died in the Shoah. It is hard to put this figure into context because the club’s membership rolls have disappeared. But for a club that was active for twenty-nine years (1909-1938) and enrolled 2,500 to 3,000 members annually at its peak, thirty-seven deaths seems a relatively low figure. We can compare it to the overall death rate for Austrian Jews in the Holocaust, which was an appalling 35%. The Hakoah story “ends” in some ways with destruction, but it also contains longer histories of dispersion, diaspora, and the lives of refugees.

MW: Thank you, Michael, for the very rich interview!