Uplifting Human Rights Leaders Through Documentary Filmmaking

The Observatory on Disappearances and Impunity in Mexico is an international academic and advocacy collaborative established in 2015 to investigate, analyze, and combat patterns of impunity regarding enforced disappearances in Mexico. Its three principal investigators, HRP Director Barbara Frey, Professor Leigh Payne of Oxford University, and Professor Karina Ansolabehere of the Institute for Legal Research (IIJ-UNAM) and the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO-Mexico) have been working with undergraduate students, graduate students and alumni to explain disappearances in México as a means to bring an end to this terrible pattern of human rights violations.

This spring the Human Rights Program will publish a comprehensive web-based report and database discussing the UMN-based team's component of the project. The virtual launch of this website and the Human Rights Program’s findings will take place on Thursday, April 22 at 12:00 Central Time. Leading up to the report release, this three part series shares three blog posts by key members of the Observatory team. This second blog installment by Hunter Johnson covers his documentary Until We Find Them. The blog entries were originally posted to Observatorio Sobre Desaparición E Impunidad En México in Spanish and English. The English version is being reposted here with permission from the Institute for Legal Research at UNAM and FLACSO-México.

Raising International Awareness and Uplifting Exceptional Leaders through Documentary Filmmaking

(originally posted 2/25/2021)

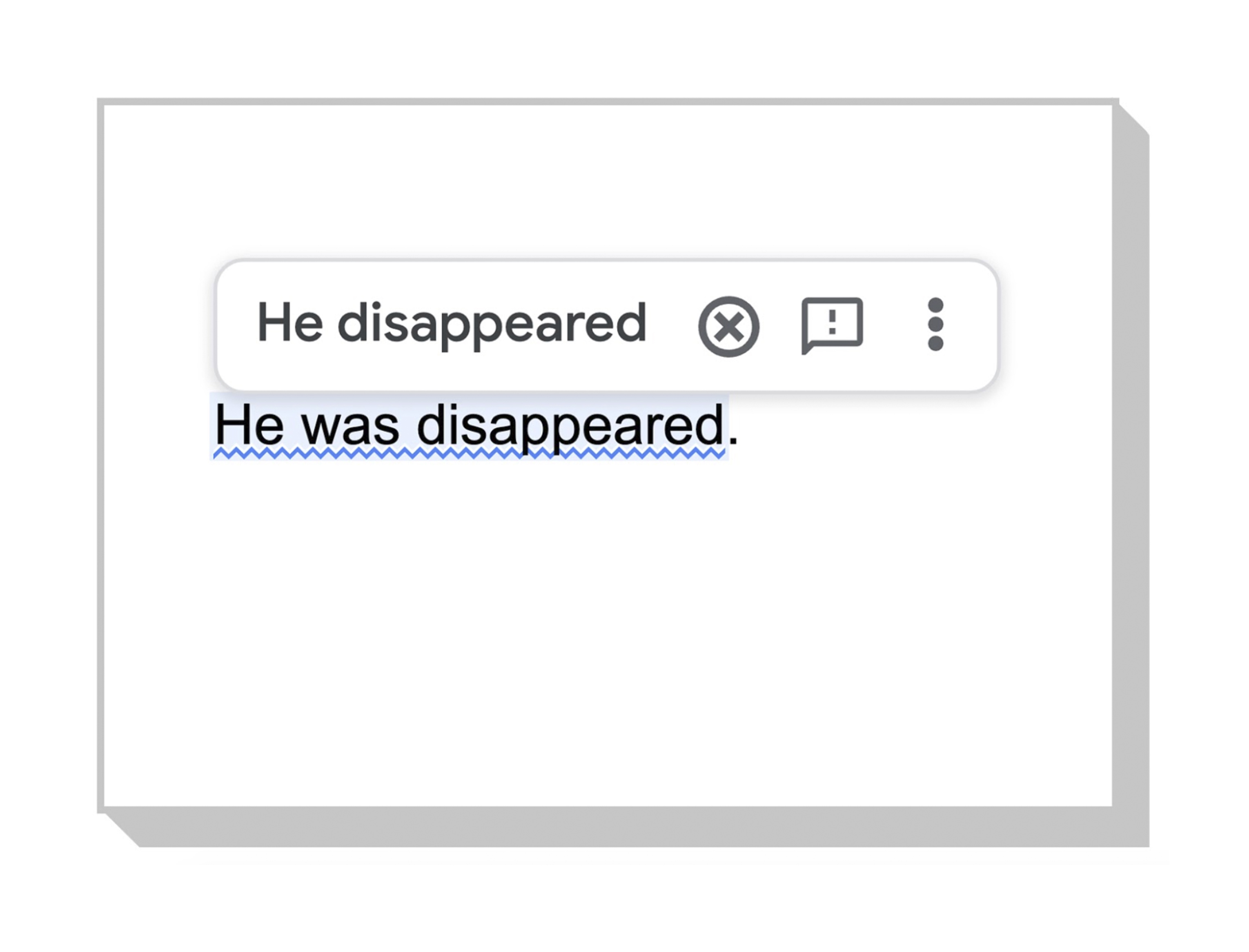

While creating English subtitles for my documentary project (consisting of two short films), something quite peculiar happens: My computer intervenes. “He was disappeared” is not grammatically correct, it tells me. The words are autocorrected to “He disappeared.” Certainly I must have made an error, my computer assumes.

“People are disappeared” isn’t accurate either, it figures, changing the words to “People have disappeared.” As I translate the words spoken by the films’ subjects -family members of the disappeared, State Search Commissioners, independent journalists -the computer continually corrects my “poor” grammar. And so, I must change it back; I must return it to the way they had intended when they shared their truths.

But why? Why can’t my computer understand what it means to be disappeared?

Example of my computer’s autocorrect

Because, according to the English language, to disappear is more commonly defined as a mysterious occurrence that happens to someone, not a malicious act that one person commits against another.

In this seemingly-harmless process of autocorrecting the words, my computer unintentionally does something much more sinister: It removes all responsibility for the action. My computer assumes there is not a bad actor behind-the-scenes carrying out this grave human rights violation. It assumes that this horrific crime is not a rampant pattern within a violent context in Mexico, characterized by widespread organized crime and government corruption. It assumes there are not tens of thousands of families engaged in a perpetual search for their missing loved ones, mobilizing in the streets to demand action, truth and justice from their country.

My computer's misunderstanding is not unlike the perplexity many people outside of Mexico experience regarding the country’s ongoing crisis of enforced disappearances. People tend to have a vague and confused understanding of the nature of this crime, and of the immensity of its scale. Most have heard of the infamous Ayotzinapa case of the 43 disappeared students, as this gave rise to tremendous national mobilization and sparked outrage on an international stage. But beyond this atrocious incident, public understanding around the issue of disappearances runs shallow outside of Mexico.

Curiosity and potential for solidarity, however, does not.

For the last three years, I’ve worked with the Observatory in several capacities. Working with Human Rights Program Director Barbara Frey at the University of Minnesota, I’ve joined a team of researchers to create a database of Mexican press articles on disappearances to study what information is provided to the public about these crimes. I’ve also contributed to a book chapter with Professor Leigh Payne from Oxford University that explores the use of visual images of the disappeared as a tool of power.

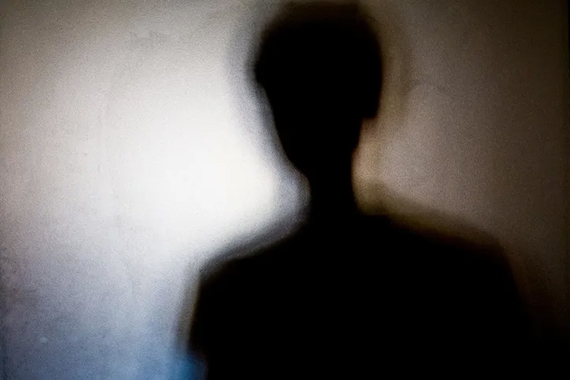

Mainly, my role has been one of a storyteller. While most of our research at the University of Minnesota consists of large amounts of data, allowing us a bird’s eye view of the overarching patterns of disappearances, we also wanted to supplement this information with personal stories. As a filmmaker and photographer, I consult with our team to identify ways the Observatory can personalize and visualize its work; add a layer of intimacy and narrative through moving images; and help an international audience understand the crisis of enforced disappearances, not only as patterns or statistics, but also as true stories of real people with human faces.

Through our connections with FLACSO and other Mexican partner organizations, we are connected to an extraordinary human rights community consisting of individuals who have dedicated their lives to confronting the issue of enforced disappearances. A few of these courageous people are the subjects of my two short documentary films which aim to bring international awareness to the issue of disappearances, and highlight the important work of exceptional individuals who are confronting this injustice.

The first film features the marriedteam of Darwin Franco and Dalia Souza, independent journalists working with ZonaDocs, a news collective with a human rights perspective in Guadalajara. Darwin and Dalia conduct in-depth investigations into disappearances on a case-by-case basis, working closely with families and collectives to seek truth and demand justice. The second film is about Sol Salgado, the lead Search Commissioner in the State of Mexico. Sol leads one of the most effective search teams in the country. She works directly with family collectives to launch large-scale searches for their loved ones. She does so with great professionalism, dedication, and empathy.

Throughout this process of filming and editing, I’ve encountered many challenges: Deciding what content to exclude when every anecdote carries profound informational and emotional weight; shaping a narrative which accurately encompasses the difficulties faced in confronting disappearances, but also one which will not overwhelm audiences into a state of inaction; balancing the suffering of the families with their tireless strength, motivation and dignity. In spite of the storytelling hurdles, I’m confident these protagonists are excellent vessels through which to explain the crisis to newcomers, while also serving as admirable examples of passionate leaders who are relentless in their efforts to help families locate their loved ones.

The films are nearly completed. When I screen scenes of them to audiences in the United States, people become thoroughly engrossed by the issue. They feel concerned for the victims and their families. They are infuriated by the impunity that runs unabated. They are eager to learn more about our country’s own role in the crisis, and how they can help from afar. This genuine concern means there is a real opportunity to inform and engage a global audience, be that on the internet, in the classroom, or at human rights events around the world.

I’ve since adjusted my computer not to mistakenly autocorrect the subtitles of the films. And with these stories, I’m hoping to make a similar change in the consciousness of an international audience -helping them understand the nature of disappearances, to empathize with the victims and their families, and to be moved to action. Because heightened international solidarity will assist in the most important task of locating all those who are missing, seeking truth and justice for the families, and assuring these violations will not be repeated.

* * * * *

View the trailer of Until We Find Them