Criminal Justice: A Public Good or a Capital Venture?

Joshua Page did not set out to study the criminal justice system when he entered graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley. “This was before people started talking about mass incarceration as a public issue,” says Page.

However, Page came across an opportunity as a teaching assistant in a college program at San Quentin prison—a degree-granting prison program unique to California. This experience started as a volunteer opportunity and eventually formed the topic of his master’s paper: funding of higher education in prisons. His experience providing a fundamental resource to one of the country’s most overlooked populations was extremely pivotal in Page’s personal, intellectual, and political development.

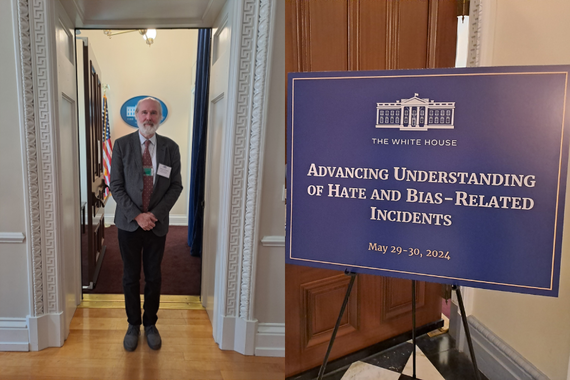

Joshua Page is now an associate professor of sociology and law at the University of Minnesota, and he is hoping to shed light on exploitation in the criminal justice system in order to enact future change.

The Justice System at a Glance

Page’s current research revolves around the bail bond industry and other criminal justice institutions that extract an enormous amount of resources from low-income communities. “Almost everything is financialized at this point,” explains Page. “If you want to send money to someone in prison, you pay a fee for that, and if you want to send a package to a prisoner, you do it through a private corporation.” Even the telephones that inmates use to communicate with family provide huge revenues to telecom companies through fees from inmates.

But corporate exploitation is not the only issue in the bail industry. The issue is that these profits depend on “resources from the most desperate and vulnerable populations,” says Page. “When people go to court, they are charged bail fees regardless of whether they are convicted or not.” Not only are prisons and the bail bond industry earning profits, but they are making those profits off of an already vulnerable population and promoting a system of “user-fees” charged to individuals who often haven’t been convicted of any crime.

A Gendered System of Care

Often, the people who end up paying bail are not the ones arrested, but those with relational ties to the accused. “When we think about bail, we often think it’s about the people who are in jail and need to be bailed out,” explains Page. Rather, “profits depend on extracting money from this enormous ‘other’ population co-signing the bails and putting up the money.”

As a result, those charged with a crime—primarily low-income men of color—are not the only population to consider when analyzing social and economic effects of the bail bond industry. It’s the people in their support systems who end up stepping up to help when called.

And it turns out the vast majority of these individuals are women. “Mothers, girlfriends, exes are wrapped up into this ethic of care that they feel a responsibility toward,” says Page. In turn, the bail-bond industry is earning its revenue off of a low-income, primarily female population roped into the system by relationships they are often looking to escape. Page recalls one example of a woman who had finally gotten out of a relationship with an imprisoned partner, but she was called shortly after to help with bail when he was charged with a crime. “They feel obligated,” Page explains, “based on this gendered system of care that can really complicate things and bring up [the issue of] who has obligations to who.”

Shifting Perspective

“We call this a criminal justice system and often assume that everything is geared towards justice and public wellbeing,” when in reality, Page says, “so much of what happens in the criminal justice field has become focused on generating resources and revenue for both the state and corporations.” Not only do private operations reap benefits from these practices, but the state itself seeks profits due to the lack of proper funding.

Page argues that states should see their prisons as a public good and be funded equitably. Rather than treating people not yet convicted as sources of income, we need to recognize these individuals as part of a greater system exploiting their already vulnerable circumstances.

The first step toward generating a will to change is fully understanding the current system. As Page explains, the criminal justice system is one that is largely misunderstood. From financial practices to social constructions, many things that happen “behind bars” are also hidden from public view and, as a result, lack the light necessary to recognize the need for change.

This story was written by an undergraduate student in CLA.