Nicola Grissom and Scott Vrieze

Just as the Human Genome Project celebrated the publication of the whole human genome in spring 2003, Scott Vrieze, then a junior at the University of Minnesota, and Nicola Grissom, then a senior at Reed College, were finishing up their undergraduate work and making decisions about what was next. Grissom would attend graduate school in psychology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, while Vrieze would do graduate work at Minnesota, his alma mater. Each would then pursue post-doctorate programs and faculty positions. By the time Grissom and Vrieze joined the faculty at the University of Minnesota, they were each focused on research in behavioral genetics.

When asked 'why' behavioral genetics, Nicola Grissom, assistant professor speaks of a lifelong curiosity about why some people are more at risk for developing mental health issues, while others are more resilient. Grissom recognizes that mental illnesses can run in families, but she reminds us that not everyone is affected similarly, and sometimes even though people may share most genes and the same home environment, they may have very different life trajectories. Grissom attributes how she approaches science—be careful, precise, and focus on meaningful work—to her graduate student adviser at Michigan, Seema Bhatnagar, PhD, and her postdoctoral supervisor at the University of Pennsylvania, Teresa M. Reyes, PhD. Grissom is proud to have been a student and trainee of these two strong scientists—both women of color and leaders in their fields.

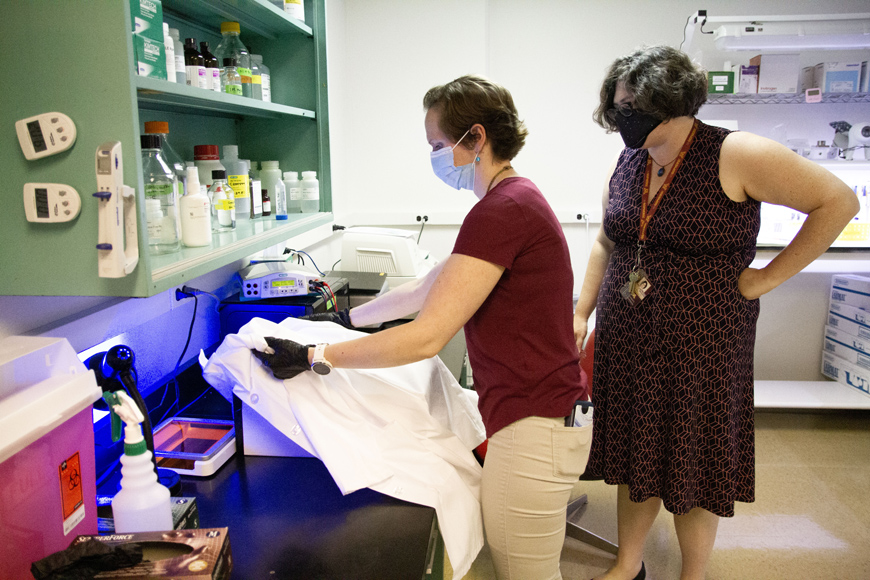

In recent research, Grissom considered mice with a set of gene variants identical to those in people who had been diagnosed with autism and ADHD. Grissom's lab teaches mice to use a touchscreen in order to get a reward—a little bit of milkshake. These same mice are then presented with multiple touchscreens, some when touched produce a reward, and some do not. What can genetics tell us about how mice learn which touch screens produce the milkshake and which do not?

Positing that there may be gender differences, some of Grissom's published work indicates that male mice with the gene variant related to autism in humans need more attempts to identify the reward-producing touchscreen than males without the variant or females with the genetic variant. In other research, Grissom has found that male mice with a normal genetic variant seem to explore more in making decisions while females explore less but analyze their sources more thoroughly. So, what is the role of gender variants in decision-making and how do such variants interact with those that model human genetic variants associated with autism and ADHD diagnoses? And what can these mice models tell us about humans?

Grissom reminds us that genes matter, but they are not necessarily determining of specific outcomes; genes code for proteins and the role of those proteins in human emotion and behavior is complex. Grissom was recently awarded two major grants on which she is the principal investigator (PI): she is the sole PI for a five-year grant that studies mice to consider the possible role of gender in decision-making and she is a co-PI for another that studies mice to understand information processing and psychosis. Grissom is working in the tradition of her teachers, doing meaningful, lifelong work.

After college graduation, Scott Vrieze, associate professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota, worked with the court system in Minneapolis with juveniles in dire need of mental health intervention. Vrieze grew concerned about children with high rates of recidivism. Could he predict who might offend again and, even beyond prediction, could he begin to understand why some would and others would not?

As a student, Vrieze was attracted to those professors who practiced skepticism—skepticism about their own work and that of others. His University of Minnesota doctoral advisers included Will Grove, past associate professor, and Matt McGue, Regents professor. According to Vrieze, the biggest challenge facing those who study behavioral genetics today is to move beyond correlating genetic profiles with behaviors toward identifying why such correlations exist. Vrieze may suggest that correlation infers causation but he will always be looking for if and how such conclusions could be refuted. Skepticism and a strong commitment to empiricism—a lineage from his teachers—are hallmarks of Vrieze's practice of science.

Vrieze's research includes two methodologies, the first being the use of 'big data' and the identification of gene variants with certain traits and behaviors. The human genome has more than 20,000 different genes arranged in over 3 billion different DNA base pairs. Some of the datasets the Vrieze lab works with require international collaborations with hundreds of scientists and millions of research participants, many coming from national repositories such as the UK BioBank which includes a half million subjects. In order to identify meaningful sequences of genes that correlate strongly with a specific behavior, the sample sizes need to be large and the computers need to be super.

A second methodology used by Vrieze's lab is the twin study. Over the past century and a half researchers in behavioral genetics have used such studies as one way to make stronger causal inferences in those domains of psychology where true experiments are not possible. Because identical twins share the same genetic profile and—often—a very similar childhood environment, differences between them can be attributed more directly to their different life experiences. Thus, the differences in measurable behavior from something as seemingly straightforward as a physiological response to a stimulus or something much more complex such as mental illness may be more clearly related to disparate experiences of traumatic events or different peer groups. In other words, behavioral genetics is a discipline very much focused on understanding how our experiences affect our lives. Vrieze is one of the directors of the Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research, a long-term longitudinal study of twins in the upper midwest.

Vrieze has led a number of well-funded grants from the National Institutes of Health, including large international studies to better identify and characterize genes that affect risk for addiction and mental illness, as well as studies comparing addiction patterns among pairs of twins living in states with different laws on recreational marijuana.

The study of behavioral genetics has never been uncontroversial and Professors Grissom and Vrieze recognize the ongoing debate. Recently, one of their colleagues, James Lee, associate professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota, wrote a piece for the Wall Street Journal voicing concerns about the use of polygenic screening by parents to identify an embryo with the genetic profile they prefer. Professor Lee knows that his research and that of his colleagues could be used in such a way that may ultimately have unwanted impacts on the development of humans as a species. Another colleague, Moin Syed, assistant professor in psychology at the University of Minnesota, and graduate student PL Nguyen have a commentary in Behavioral and Brain Sciences in which they specify a need for "sophistication in our conception of culture" as scientists begin to develop a framework for bringing together cultural perspectives and behavior genetics.

In considering these long-standing historical challenges and current controversies, Grissom foregrounds our need for neurodiversity, the celebration of a diverse palette of human neurology, including those profiles which today we may not understand but which may be important for humanity's future. Vrieze reminds us that the study of human behavioral genetics is in its infancy as most of the human genetic variation has not even been discovered, due largely to the lack of research in Africa, where there is more genetic diversity than the rest of the world combined.

Grissom and Vrieze agree: being open to human diversity and skeptical of what we do not fully understand—just twenty years after mapping the human genome that has been evolving for millennia—is good science.