Coahuila

Located in the northeastern region of Mexico, Coahuila de Zaragoza, more commonly referred to as Coahuila, is one of the 32 states that makes up the United States of Mexico. This state is composed of 38 municipalities, with its capital being Saltillo. One of the largest and least densely populated states in the country, it shares borders with Texas to the north, Chihuahua to the west, Nuevo León to the East, and with Durango and Zacatecas to the South.

Disappearances in Coahuila

The increasing presence of violence in Coahuila led to the increase in the number of disappearances observed in this region. As of February 2020, the government reported that 3,328 individuals have been disappeared in the state. This figure includes both those individuals who remain disappeared as well as those who have been found.

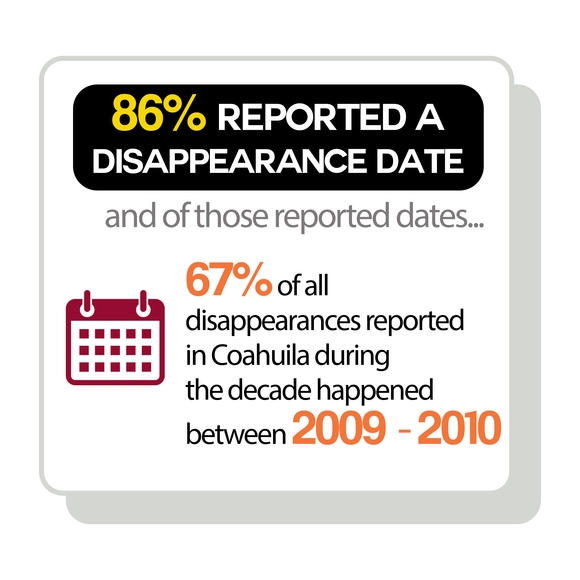

The Observatory’s press database contains 196 press-reported disappearances between 2009 to mid-2018, with a high number occurring in 2009 and 2010 (90 victims, 46%).

|

|

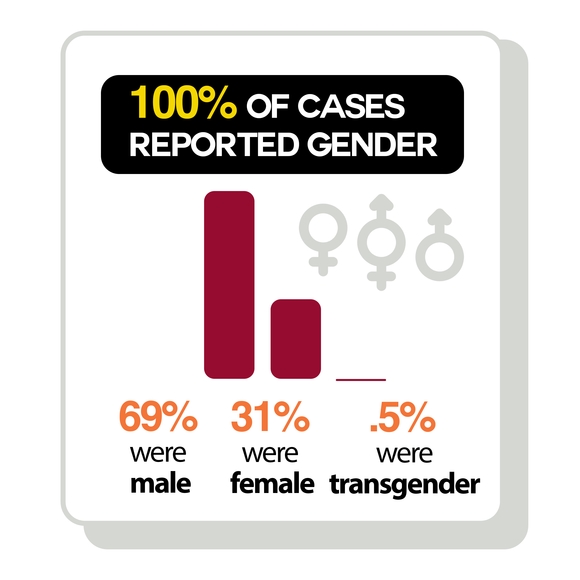

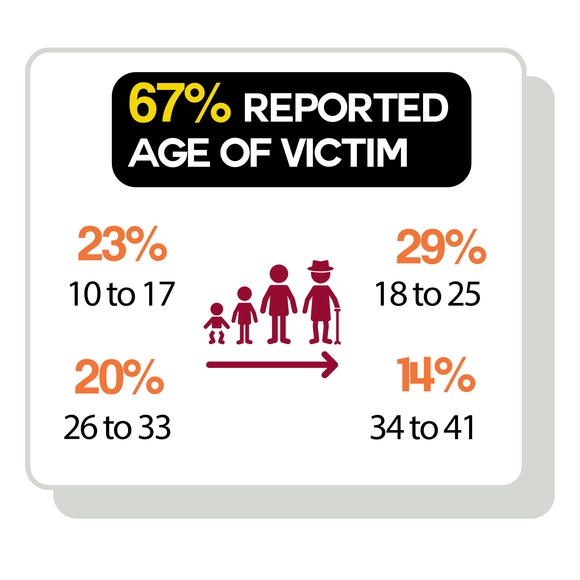

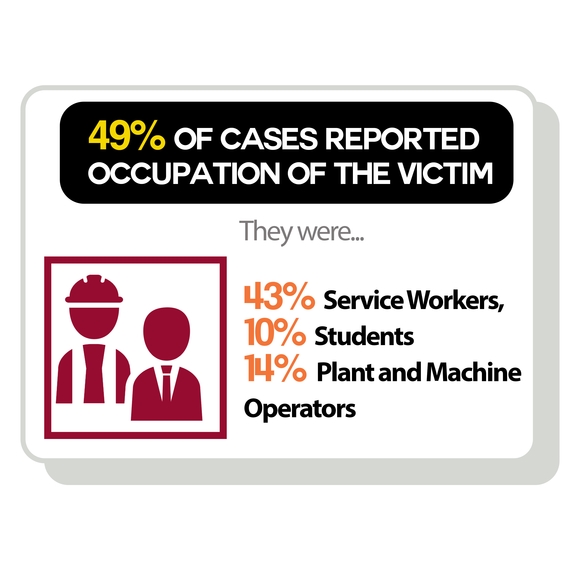

Those at highest risk of being disappeared are men in transit by foot or car-- many of whom are chauffeurs or entrepreneurs-- between the ages of 17 and 37, with the average age being 29 (Observatorio, 2019). The press database confirms these findings: according to the information collected on reports published by the press in Coahuila on disappearances, nearly 7 out of 10 (69%) of the victims of disappearances are reportedly male, the average age was 26.

|

|

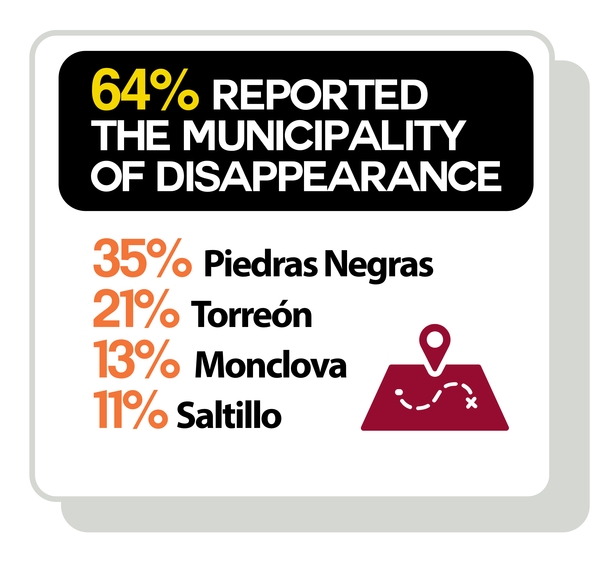

The data gathered from press reports by the Observatory found that --when the press reported a location of disappearance-- most victims disappeared from a place familiar to them or while in transit (80%). While disappearances have been registered in 18 of the 38 municipalities of Coahuila, those areas with the highest rates of disappearances are at the borders -- Torreón and Piedras Negras -- which have become zones of violence.

|

|

Persons from marginalized groups, such as migrants, are at a relatively higher risk of being disappeared, especially given Coahuila’s long border with the United States. Piedras Negras is one of the primary points where northbound migrants may cross the Rio Grande into the United States. Despite this, we found that the press rarely reported on the nationalities or personal backgrounds of the victims in Coahuila.

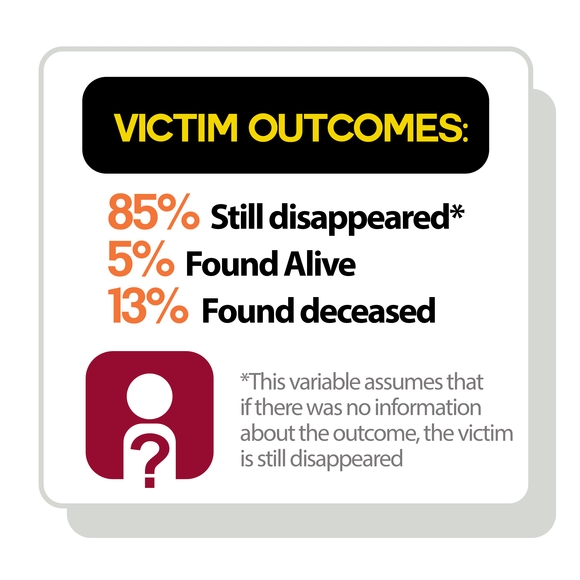

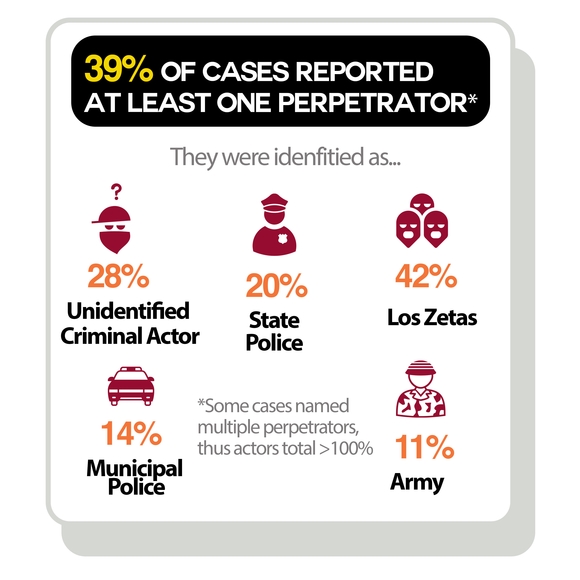

According to FLACSO, a vast majority - close to 80%- of disappeared individuals in Coahuila remain disappeared. It is rare for victims to be found dead or alive. The findings from the press database support this disheartening statistic: in only one of five cases in Coahuila did the press report an official search for the victim. In 85% of cases, the press reported the victim as still disappeared, or did not report an outcome. Both state officials and members of organized crime groups have been identified as the perpetrators of disappearances; many suspect that members of the military division, Grupo de Armas y Tácticas Especiales (GATE), have been responsible for disappearances and that, additionally, state and federal actors collaborated with Los Zetas in the orchestration of disappearances (Observatorio, 2019). The press database corroborates these findings; when a suspected perpetrator was identified by the press, Los Zetas were the most frequently reported (32 cases). Additionally, the press reported state actor involvement: state police (15 cases), municipal police (11 cases), and the army (10 cases).

|

|

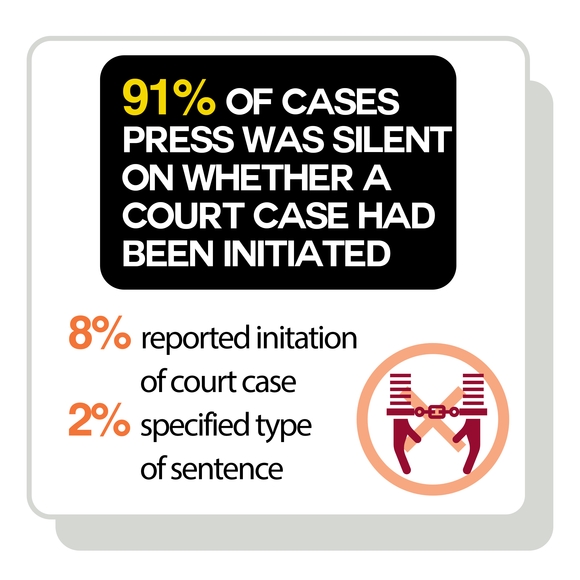

In Coahuila, even in reported court cases, justice was elusive. In many cases, the legal system is portrayed by the press as functioning in a superficial manner, with charges dismissed against many suspected perpetrators, most notably if the alleged suspect had money and power. For example, in the case of the disappearance of Jose Antonio Robledo Fernandez (Toño), charges against Carlos Enrique Haro Villeral- a businessman linked to Toño’s employers- were dropped despite the presence of lethal weapons and folders containing information on the victim in his house. The judge declared that it was insufficient to bring charges against this businessman.

Cases reported as being seriously investigated by the authorities typically involved the disappearance of an important official, a group disappearance, corporate corruption, or a combination of the three. The case of Atzy Adamary Reina Saucedo, a mother of two who disappeared from Allende along with her husband and five other individuals, highlights the fact that group disappearances also tend to attract both legal and popular attention. In cases in which ordinary individuals were reported to have disappeared alone, the press almost never reported on subsequent legal investigations, suggesting the disappearance of justice as well, their case just another unexamined file in the seemingly bottomless file drawer of impunity in Coahuila.

|

|

Impunity

In Coahuila, even when the court cases resulted in convictions, justice was not guaranteed for the victims and their families. In many cases, the legal system was portrayed by the press as functioning in a superficial manner, with charges frequently dismissed against suspected perpetrators, especially if they had money and power. For example, in the case of the disappearance of Jose Antonio Robledo Fernandez (Toño), charges against Carlos Enrique Haro Villeral--the businessman that managed the security company contracted by Toño’s employers-- were dropped despite the presence of lethal weapons and folders containing information on the victim in his house. The judge, in spite of the incriminating evidence, claimed insufficient evidence to support charges against this businessman.

The cases reported as being seriously investigated by authorities typically involved the disappearance of an important official, a group disappearance, corporate corruption, or a combination of the three. The aforementioned case of Jose Antonio Robledo Fernandez illustrated the fact that corporate involvement in a disappearance tended to attract attention from both the press and judicial system. Group disappearances also attracted more attention. Atzy Adamary Reina Saucedo, a mother of two who disappeared from Allende along with her husband and five other individuals, received attention from the press and the criminal justice system. These kinds of cases were the exception. The thousands of everyday cases in which individuals disappeared by themselves usually went unreported, and if they did appear in the press, there was no apparent follow-up by the press or the courts.

As of 2015, Coahuila had a population of 2,961,708, heavily concentrated in its three most prosperous urban centers; Saltillo, Torreón, and Piedras Negras. In fact, 50.3% of the population is concentrated in Saltillo and Torreón (Observatorio sobre Desapariciones e Impunidad en México, 2018). Despite its relatively small population, Coahuila is able to generate a GDP that places it among the ten wealthiest states in Mexico, at 836.40 billion pesos, or about 38.68 billion USD. While Coahuila is home to 33,990 businesses and a strong formal economy, the size of its informal economy is considerable; 35.9% of the economically active population is involved in the informal sector of the economy.

Coahuila can be divided into four regions that are characterized both by their economic output and geographic location. The border region, located at the north of the state, is characterized by international business and its mechanical industry. Control of this region is valuable for those looking to turn a profit through both legal and illicit avenues. The Laguna region, whose center is Torreón, is a political and economic powerhouse with a profitable and high-end industrial sector. The southeastern region of this state, which borders Nuevo León, is the site of the state capital, Saltillo. The fourth region is the central region, characterized by a dry, desert-like climate, and known for its steel-making industry and comparatively low rates of disappearances (Observatorio, 2018). Coahuila’s desert is known for its geological preservation. Along with robust wine production, dinosaur fossils drive its “Dinos y Vinos” tourist economy.

The Human Development Index (HDI) of Coahuila is the fifth highest in Mexico; the average resident of Coahuila has received 9.9 years of formal education, with 21.4% of residents seeking higher education, figures which help to keep the illiteracy rate low, at 1.97%. The unemployment rate, as reported during the first trimester of 2020 was 4.73%; the majority of those living in this state are gainfully employed.

Despite the high quality of life implied by these statistics, Coahuila is marked by increasingly high and unevenly distributed rates of violence. In fact, while 18 of the 38 municipalities of Coahuila have reported disappearances, 75% of those occur in the municipalities with the highest development ratings; Saltillo, Torreón, and Piedras Negras. Interestingly, it appears that increasing economic prosperity—a phenomenon that tends to be associated with development and increased well being—has been accompanied by increase in violence between the years of 2008 and 2016. As this state and its urban centers become increasingly wealthy, so too do they become increasingly violent.

The political scene in Coahuila has been dominated by el Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party or PRI) for the past 90 years; this dominance is one that is characterized by the lack of any powerful or promising alternative to what has come to be the status quo. In fact, from 2005 to 2017, this party occupied 57% of the seats in the state legislature. The perpetuation of an essentially one-party system in Coahuila discredits the myth that political diversity is linked to increased levels of violence.

Government officials in Coahuila have responded to the increased rates of violence by adopting and imitating the strategies of the federal government, which have focused on public security and intense state management. Under the administration of Humberto Moreira, from 2005 until 2011, disappearances and extortions were managed in a contradictory and ineffective manner. On one hand, the administration’s response was to deny the widespread violence and the pressing problem of disappearances and to replicate narratives about the criminality of the victims. On the other, Moreira’s administration publicly proclaimed it operated under a “zero tolerance” framework, identifying violent crimes as an issue of public security, increasing the punishments for these crimes, and promising to keep perpetrators behind bars for an extended period of time. Moreira refused to meet with the families of the disappeared for three years of his time in office, which further instilled fear and undermined efforts to seek justice. (Observatorio, 2019).

While the administration of Humberto Moriera was characterized by its inability to acknowledge the gravity and full scope of the escalating violence in Coahuila, that of the subsequent Governor (and brother of Humberto), Rubén Moriera, openly recognized the problem. Governor of Coahuila from 2011 until 2017, Rubén Moriera presented himself as a scholar of and advocate for human rights who had served as the president of the Human Rights Commission of the House of Representatives and had advocated for the 2011 constitutional reform with respect to its treatment of human rights. Rubén thus approached the violence in Coahuila from a perspective that, while focused on public security, was influenced by his interest in human rights. The attention paid to disappearances and violence in Coahuila under Rubén Moriera led to the creation of spaces dedicated to conversation among government officials and human rights organizations, along with the institutionalization of search practices for missing persons. (Observatorio, 2019).

Despite the official efforts made by Rubén Moriera to recognize, combat, and address the issue of disappearances in Coahuila, little progress was made during his tenure towards locating disappeared individuals, though the average number of disappearances in the state did decrease after 2013.

Until 2009, security and peace in Coahuila was characterized and controlled by a pact that had been established between PRI government officials and criminal organizations in the region. That agreement has eroded, undermining the stability of the region and the safety of its inhabitants. Government officials in Coahuila have since imitated and implemented the very strategies designed and carried out by the Mexican government in their management of the drug cartels; namely their tendency to destabilize these groups through their “decapitation” (Observatorio, 2018). There are thick relationships between criminal organizations and state actors at all levels.

In Coahuila, the attacks against drug cartels carried out by military officials permitted the rise of “Los Zetas” -- a flamboyantly violent cartel composed of ex-military officials that had previously been sent to this region to fight the Gulf Cartel. The increase in disappearances and extortions that was observed from 2010 to 2012 -- the very timeframe in which Los Zetas consolidated their control over Coahuila -- can be indirectly attributed to the military’s engagement in low-intensity conflict, the “war on drugs”. From 2007-17, Los Zetas were hegemonic in the state. They used a model in which they exerted total control over all institutions and territories in order to minimize their risks. This resulted in the government itself promoting the ends of the criminal organization. Vazquez (2019) refers to this scheme as macro-criminality.

While the information compiled on this website was published digitally in a variety of newspapers, different news outlets were prominent in each of the states we researched.

In Coahuila, the two newspapers upon which our studies have most heavily drawn are Vanguardia and Zocalo. Both Zocalo and Vanguardia report on national news as well as featuring newsworthy local or regional stories.

Vanguardia

Vanguardia MX was established in 1975 to provide its Coahuila readers with up-to-date, accurate information on the happenings in Saltillo, Coahuila, and in Mexico, more generally. Its official mission statement is “exalt the population through the creation, collection, and distribution of high quality news, entertainment, and information, with ethical business actions that promote an improved quality of life for its employees, environmental stewardship among, and active community participation”.

Zocalo

Zocalo, a news outlet with an online and radio presence, also reports on events in Coahuila. This business has locations throughout Coahuila, in Piedras Negras, Monclova, Saltillo, and Acuna. In addition to reporting on happenings in Coahuila, it also relays to readers that which occurs to the North, in Texas.