Guerrero

Guerrero is a southwestern state bordering Oaxaca to the east, Puebla to the northeast, Morelos and Mexico to the north and with Michoacan to the northwest. The state has seven regions—Acapulco, Zona Centro [center zone], Zona Norte [north zone], Costa Grande [big coast], Costa Chica [small coast], Montaña [mountains] and Tierra Caliente [hot lands]—and 81 municipalities. Among these municipalities are the state's capital, Chilpancingo, and Acapulco, its most populous city. The population of the state, as of 2015, was about 3.5 million.

Disappearances in Guerrero

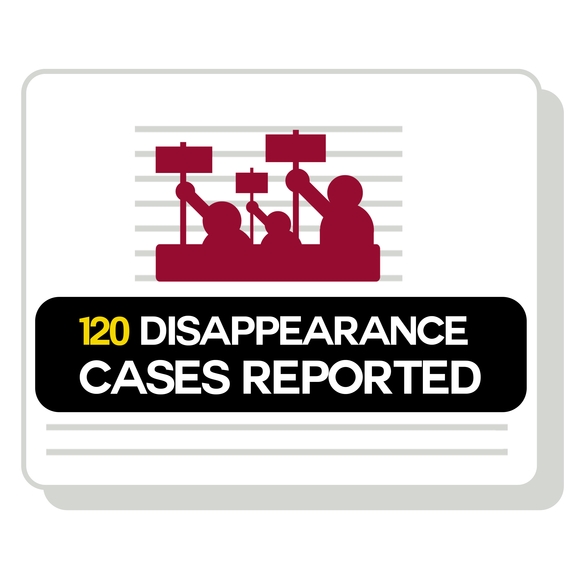

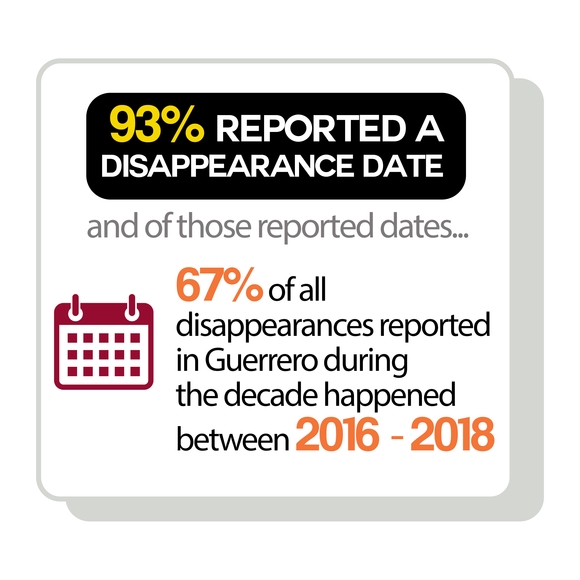

According to the Registro Nacional de Personas Desaparecidas y No Localizadas (RNPDNO), between 2009 and 2018, there were 3,061 missing and disappeared persons in Guerrero. The Observatory’s press database contains 120 cases of disappeared victims in Guerrero during this time period. The press reported the highest number of disappearances from 2016 to 2018, a much later peak in cases than in the other three states (the press database specifically excluded articles about the case of the 43 students who disappeared in 2014 in Ayotzinapa in Guerrero, an exceptional case that generated enormous press coverage nationally and internationally.) This three-year time period, 2016-18, accounts for two-thirds (67%) of all disappearances reported by the press in Guerrero during the decade, with a total of 75 victims.

|

|

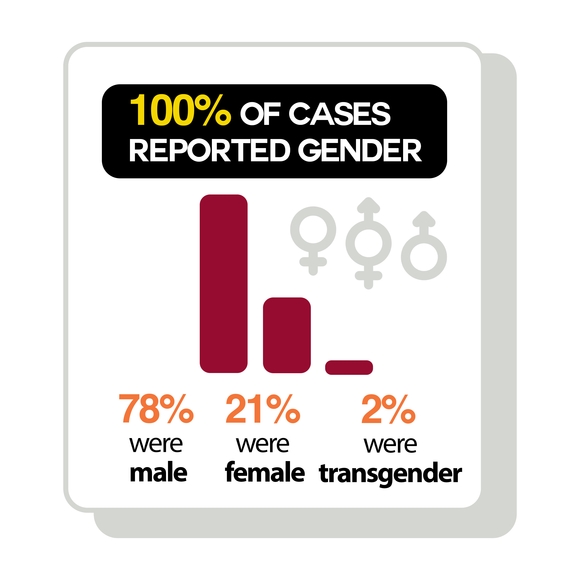

In Guerrero, just over half (53%) of victims reported by the press disappeared in a group and half (47%) disappeared alone. Nearly 8 out of 10 (78%) of victims were male, 2 of 10 (21%) were women, and two victims were identified as transgender.

|

|

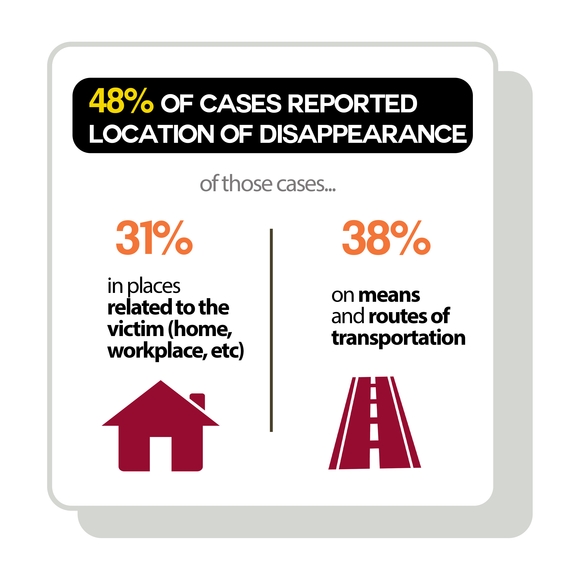

When the press reported a location of disappearance, nearly a third (31%) of disappearances occurred in places related to the victim (house, workplace, private property) and over a third (38%) occurred or on means and routes of transportation.

|

|

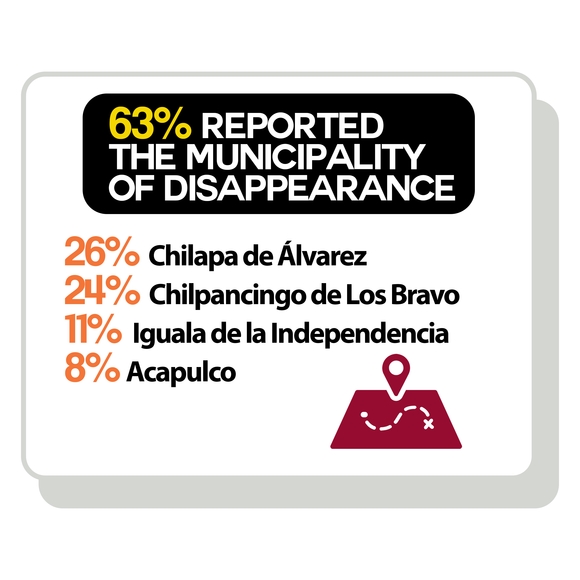

Disappearances were reported in 19 of the 81 municipalities in Guerrero. Of cases where municipality was reported, the highest reported disappearances were Chilapa de Alvarez (26%), Chilpancingo de Los Bravo (24%), and Iguala de la Independencia (11%).

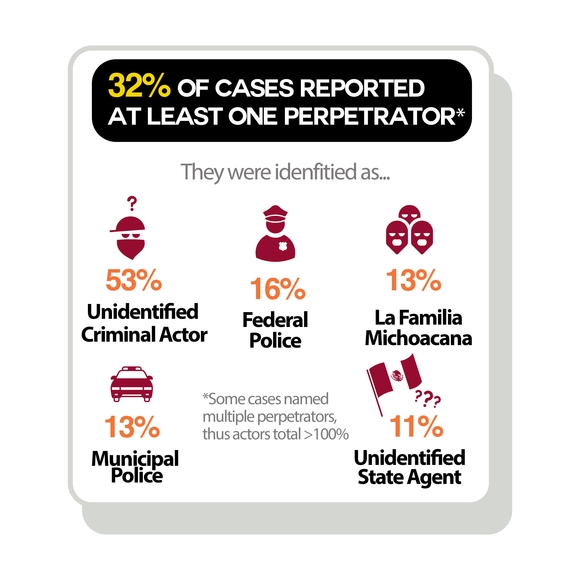

Notably, disappearances in Guerrero tend to involve state officials; from 2014 through 2018, Guerrero is reported to have the most disappearances involving the participation of state officials or security officers in the nation.

|

|

In Guerrero, the press did not report a suspected perpetrator in 68% of cases. When a perpetrator was reported, 50% were unidentified private actors (not identified as affiliating with a specific criminal organization).

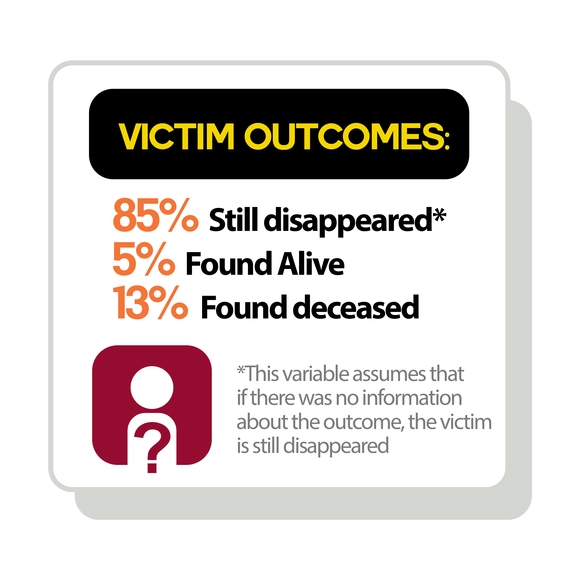

According to the national registry, RNPDNO, the majority of disappearances reported in Guerrero remain unsolved. The press database supports this pattern. According to the press reports, 59% of victims remain disappeared or no outcome was reported. Nearly 4 of 10 (38%) of victims were found deceased and 1 of 10 (11%) victims were found alive. In Guerrero, the press reported a markedly higher number of deaths in disappearance cases compared to the other states.

|

|

In response to the cases of enforced disappearance, various grassroot and NGO organizations in Guerrero have stepped up to support families of victims seeking knowledge and justice. Well-known organizations within the state include Centro de Derechos Morenos, El colectivo de desapariciones de Chimalacacingo, and Fundación de Ayuda al Débil Mental. Community members have organized together to form protests, talk with elected officials, form coalitions with other organizations and raise public awareness about enforced disappearances and impunity. In the wake of the disappearance of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa, local organizations made up of families of the disappeared are credited with popularizing the technique of searching open fields for evidence of new burial sites, a method which is now used to look for graves of the disappeared all over the country.

A downloadable PDF of these infographics is available here.

Ayotzinapa Case: The "43"

A group of about 100 students from Raúl Isidro Burgos Teachers’ College teaching college in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, known for its social activism and indigenous roots, took control of various buses to attend a protest. Taking control of buses to go to protests is commonplace and accepted in Guerrero as it fits in with the larger public narrative of civil resistance. The students boarded multiple buses on September 26, 2014. The details of the events that took place that day still remain unclear. However, by the end of the day, six people were killed and 43 students had been forcibly disappeared. They have yet to be found.

Here is a helpful timeline of the case, created by students at Rutgers University. On September 26, 2014, the students from Ayotzinapa were trying to go to Chipancilgo but the roads were blocked so they decided to instead go to Iguala. Their plan in Iguala was to disrupt an event being held by the mayor’s wife before making their way to the protest in Mexico city to commemorate the 1968 student massacre.

At about 9:30 p.m., the students were riding the buses in Iguala when local police in Iguala began to shoot. There is not a consensus as to if all the students were in buses at the time or if some were hitchhiking outside the vehicles. There was a chase where the students kept urging the buses forward as they were being pursued by the police until they reached a patrol car blocking the road. Some of the students tried to lift the patrol car to clear the roadway, but they could not move it and the police opened fire at the students, with three students sustaining injuries and another suffering an asthma attack. Eventually, an ambulance arrived to take those four students to the hospital, leaving the rest of the students with the police.

The 43 students were disappeared in two incidents:

At 9:40 p.m. a group of the students riding in some hijacked buses were stopped by police close to the northern beltway. The police flushed the students out by pumping teargas into the bus. As they disembarked, the police took them into custody. Some students were able to evade capture and hide in the surrounding woods.

At 10:50 p.m. the police rounded up dozens of students hiding in another one of the buses and took them away from the scene in patrol cars.

A third group of students on buses received word of the other attacks and decided to abandon their bus and run into the woods on foot to hide. The contingency of students hiding in the northern beltway began to emerge from their hiding spots at 11:00 p.m. They returned to the scene of the crime to document evidence and try to contact their classmates. Journalists and teachers began to come as well, and they started a spontaneous press conference until multiple vehicles came and they were shot at by three men. Two men were killed and others wounded and the survivors fled into the surrounding area. It is still unclear who exactly shot them.

The first investigation became almost as infamous as the case of disappearance itself: it was an investigation emblematic of the impunity and government collision with organized crime that Mexicans across the country have witnessed in their own lives. Many human rights experts on the world stage accuse the Mexican government of purposeful mismanagement of the investigation.

México’s Attorney General, Jesus Murillo Karam, did not want to use evidence contradictory to his theory, which he called “the historical truth.” The government account is that the 43 students were kidnapped by local police who handed them over to a cartel that incinerated their bodies in a garbage dump. They also refused to acknowledge that higher level government officials were involved in the disappearance.

This version of events has been opposed by international human rights experts who considered it improbable. At first, the government’s invitation to the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) to provide international technical assistance in connection with the Ayotzinapa case demonstrated its desire to be transparent about the investigation of the internationally condemned crime. But, soon, the government would not allow the international investigators to interview anyone from the army present near the scene of the crime. Ultimately, some international experts stated that they preferred leaving the country rather than lending legitimacy to a toothless effort due to the barriers imposed by the government. It was revealed after the fact that the government also used malware to spy on international experts and lawyers for the families.

The United Nations reported that many of the initial witnesses and suspects in the case were subjected to torture. After considering all this information, the three judges of the First Collegiate Tribunal of the 19th Circuit decided to null the previous proceedings and establish a truth-commission to manage a new investigation. This ruling is significant because voiding the initial investigation cannot be appealed by the government. This new investigation is expected to be led by the families of the disappeared, the government’s prosecutors, members of the National Commission for Human Rights and international experts in human rights and forensics. The truth-commision investigation is ongoing and the families and public are yet to receive answers or justice.

This case of enforced disappearance of the 43 was a turning point in the public consciousness about systematic human rights violations in Mexico. The explosion of public outrage manifested itself in large demonstrations throughout México and around the world. This was the first major case to permeate the international consciousness.

Protest in response to disappearance of the 43

The economy of Guerrero is sustained, in large part, by its tourism industry. While Guerrero attracts visitors across the entirety of its territory, tourism is concentrated in an area referred to as Triángulo del Sol [the triangle of the sun] which spans Acapulco, Taxco and Zihuantanejo. Acapulco, in particular, is considered to be a key tourist destination not just for the state, but the country overall, specifically with respect to the economic revenue it generates. The tourist sector in Guerrero is diverse and includes ecotourism, extreme sports, nightlife, and architectural pre-colonial and colonial structures. In a state that prides itself so highly on its status as an idyllic tourist destination, the dichotomy between this image and the reality of intense economic inequality, widespread poverty and violent cartels that ravage the residents of the state is striking.

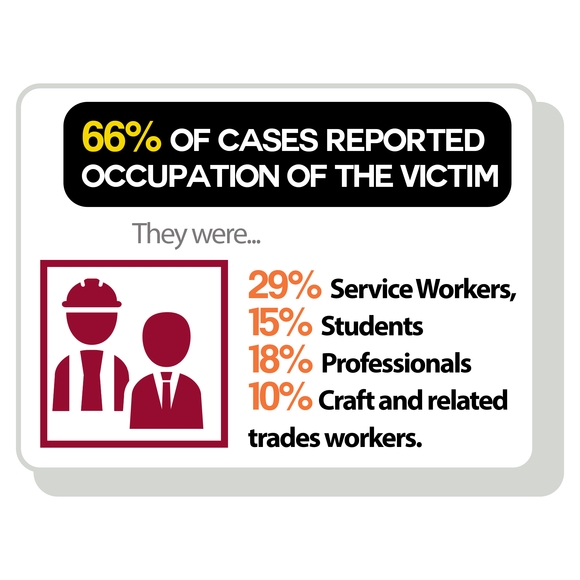

Due to the size of its tourism sector, the majority of the workers in Guerrero are employed in the service industry. Other prominent sectors include fishing, mining and agriculture. Fishing supports communities along the coast in addition to sustaining a robust commercial fishing industry. Mining is popular in this state as well, thanks to the natural mineral deposits of gold, iron and lead in this territory.

Agricultural production in Guerrero ranges from subsistence farming to international trade. This state, in addition to growing staple and commercial crops, is perhaps best known for being among the top producers of poppy flowers in the world. After coffee production fell 88% between 2003 and 2016, the vast majority of former coffee land was repurposed to grow drug crops (Lohmuller, 2016). The success of poppy production for use in heroin and cocaine, reflected the high levels of economic stress faced by farmers in the region. When NAFTA lifted tariffs on agricultural goods, farmers were unable to compete with cheap food imports from the U.S., including the central staple of corn (Grandmaison, Morris and Smith 2019). Many were, in fact, compelled to grow poppy flowers in order to support their basic needs, and the rise of organized crime in the region coincided with the elimination of protective tariffs under NAFTA.

The average yearly income per capita is 5,500 US dollars. Despite the fact that Guerrero’s GDP and economic security are average when compared to the 31 other states in Mexico, the Human Development Index (HDI) of Guerrero ranks 31st out of 32 states. The rate of illiteracy, a marker for educational achievement, is quite high, at 13.61% and symptomatic of the fact that 46% of the population over the age of 15 lacks basic schooling. Those that do access education complete an average of 7.8 years of schooling. Due to the present conditions of high unemployment and limited access to education across the state, Guerrero ranks number one out of all the states in Mexico for the rate of emigration to other states and seventh for emigration to the United States.

Guerrero is demographically diverse, especially when compared to other states in Mexico. This state is home to four indigenous groups: Nahuas, Mixtecs, Amuzgos, and Tlapanecos. There are over 20 languages spoken in Guerrero. Alongside Spanish, the most frequently spoken languages are Nahuatl (38.9%), Mixteco (27%), Tlapaneco (21.9%) and Amuzgo (7.9%). Out of those who speak an indigenous language, only 29% of them also speak Spanish (INEGI). Indigenous Mexicans make up 13% pf Guerrero's population. There are also large communities of Afro-Mexicans in the coastal region, making up the highest percentage of Afro-Mexicans of any state. Indigenous groups and Afro-Mexicans have historically and presently faced severe discrimination due to their ethnic backgrounds.

The climate of violence in Guerrero influences the functioning of the government and its susceptibility to corruption. A climate of fear is pervasive among state officials and political candidates. The International Crisis Group reported an instance in which an autodefense group set off a car bomb to persuade a mayor to honor their established quid pro quo, moving police forces out of a designated area. In such a context, individuals pursuing elected office feel compelled to negotiate with criminal operatives in exchange for votes; some even maintain direct ties to criminal groups. This fear and intimidation is not limited to government officials; citizens of Guerrero are made to vote for candidates favored by local organized crime groups through their employment of violence and threats.

Corruption is rampant among municipal and state police forces in Guerrero; a reputation which severely undermines the respect and trust of community members. 82.7% of police officers in Guerrero said that their superiors showed “improper or illegal behavior including acts of aggression against citizens as well as accepting bribes”. Additionally, 88.1% surveyed stated that their peers displayed the same types of behavior. To make matters worse, many on the force are not trained adequately, if at all, to carry out their jobs. As of 2018, 32% of the officers on the force in Guerrero had received “no training at all”. The ineffectiveness and inadequate training of police forces in this state is reflected in its high impunity rates. Impunity in murder cases is a staggering 96%, making it the third highest in Mexico.

Illustrative of police corruption, the municipality of Acapulco disbanded its own police force over “criminal infiltration”, diminishing public confidence even further. INEGI has found that 84.7% of individuals over the age of 18 in Guerrero consider their city to be unsafe. Only 17.6% of the population was satisfied with the police as of 2019.

La cifra negra, or the dark figure on crime, which measures crimes that are believed to have gone unreported, was a startling 96.8% as of 2017. In other words, the scope of crime and victimization is wider than current data shows. Having lost faith in the very institutions whose role is to project members of civil society, many decide to leave crimes unreported, contributing to the continued widespread lack of accountability in the state.

Guerrero has a history of systemic violence. Tensions related to colonialism, diversity, indigeneity and suppression have driven conflicts over the development of Guerrero since its inception. Indigenous populations and Africans forcibly brought over as slaves have faced violence since colonization; violence that has continued during the revolutionary war, the “dirty war” and the “war on drugs”.

The process of colonization is ongoing and occurs through the expropriation of indigenous lands, exploitation of labor and mistreatment of migrant workers and miners. This colonial violence is coupled with that of increasingly militarized security forces within the state, drug production and trafficking, torture at the hands of the state, and enforced disappearances. Violence has long been used as a means to repress indigenous and peasant communities in Guerrero.

For many living in this state, the colonial repression of indigenous populations is a political throughline that has existed since the 16th century. In 2017, there were 25 episodes of massive internal displacement in Mexico and seven of those episodes occurred in Guerrero, the highest number in the country. A report from the Pulitzer Center notes that indigenous communities suffer from massive internal displacement at a disproportionate rate. Out of the massive internal displacement episodes that occurred in Guerrero in 2017, 61% of the displaced communities were made up of indigenous Mexicans. This signals an alarming reality that indigenous communities are being targeted and oppressed.

Another concern to civil society is the influence that organized crime organizations have over the press. Since 2000, Guerrero has had the fifth highest reported rate of journalists murdered in the nation. The persecution of journalists creates a climate of fear, leading to censorship in media outlets. Editors and journalists engage in self-censorship on illicit behavior, rising out of the threat of violent retribution from organized crime groups. Families seeking justice may not have the option of raising awareness through the press.

In the face of such violence and oppression, a culture of activism has developed in Guerrero. The roots of this culture in mainstream consciousness can be traced to the protests realized by those galvanized to protest after witnessing the violence suffered by civilians in Guerrero during the dirty war. This paradigm of resistance has led to the normalization of political uprising among marginalized groups like migrant workers, indigenous communities, and people suffering from poverty. Such protestors often take a stand against human rights violations, impunity, lack of sovereignty for indigenous communities, and social inequality. Speaking broadly, the demonstrators do not often change the views or actions of those in power but are motivated by a historically ingrained mindset of “resistance or complicity”.

The indigenous communities in Guerrero have long borne the brunt of injustice, both socioeconomically and politically. They have also been among the most vocal in response to the impact of the insurgency of cartels and to the response from the state.

Prior to 2009, there were roughly one dozen cartels that maintained control over territory in Guerrero. However, the killing of the criminal leader Arturo Beltran Levya in that year by federal forces disrupted the power dynamics and resulted in the fracturing of various cartels. In actuality, the effects brought about by Levya’s death led to instability within the region and an increase in violence.

This case is one of many that illustrates the ineffectiveness of decapitation in the fight against sophisticated networks of organized crime. Whereas before the murder of Arturo Beltran Levya there only existed 12 cartels in the state of Guerrero, following his death, the region has come to be dominated by at least 40 organized crime groups to fight over territory in the state. Significantly, there is not a dominant cartel in Guerrero. The fact that no single criminal organization has a monopoly on the state has become an inherent danger in and of itself and has given way to an aggressive, increasingly violent competition between organized crime outlets as they jockey for territory, control over poppy fields and other revenue streams, undermining the safety of those living here. The sheer number of organized crime groups and high levels of impunity in the state have given way to a laissez-faire criminal framework.

In an effort to combat the violence of organized crime, some citizens of Guerrero have taken matters of justice into their own hands. These vigilantes self-identify as “autodefensas” (self-defenders) and strive to defend predominantly indigenous communities from criminal actors. Despite their apparently good intentions, some of these groups have strayed from the protection of their communities and have morphed into collectives that engage in and profit from organized crime themselves.

In addition to being a drug production site, Guerrero is a transshipment corridor, which attracts violence as organized criminal groups fight for control of the drug market. However, many medium and small criminal outlets do not have easy access to drug related revenue streams, so they forgo narcotics to engage in larger criminal enterprises. In the face of this, many have turned to “predatory rackets” like extortion and kidnappings for ransom. According to INEGI, almost one in five people in Guerrero has had someone try to “bully them into paying for protection”.

El Sur-Periodico de Guerrero

El Sur - Periódico de Guerrero (newspaper of Guerrero) is a news outlet based in Guerrero that caters to a local audience. Founded in 1999, this publication’s mission is to present the news of Guerrero and the world with “an analytical view and a critical attitude”. It is published in both print and online form. Along with standard sections like sports, politics and education, there is a section focused on Guerrero and a specific section devoted to the state’s largest city - Acapulco. Like many other outlets, they have a social media presence.

El Universal

El Universal is a national news outlet that is popular all across Mexico, including in Guerrero. It was founded in 1926 in Mexico City to inform readers on the ending of the Mexican Revolution and the creation of a new Constitution. Since that time it has grown to cover national current events with a following all over Mexico. Since 1996 it has had an online presence, and the publication boasts 300,000 print subscribers across the country.

El Universal has received criticism for coverage sympathetic to the government, especially during México’s Dirty War. More recently, the New York Times accused El Universal of impartiality and impropriety in their reporting, noting that “El Universal receives more government advertising than any other newspaper in the nation, about $10 million in 2017.” The paper’s leadership has direct links to the PRI, and was found to have falsely disparaged another candidate in its coverage of México’s 2018 elections. These close links to the government have impacts in human rights coverage. One journalist investigating a case of a shootout of unarmed civilians was prevented from publishing her findings because government officials were responsible for the crimes.