Jalisco

Located in the southwestern region of Mexico, Jalisco is a coastal state that shares borders with Nayarit, Zacatecas and Aguas Calientes to the north, San Luis Potosi to the northeast, Guanjuato to the east, and with Michoacan and Colima to the south. The seventh geographically largest and fourth most populous state in the country, Jalisco, as of 2015, has a population of about 8 million people. Among its 125 municipalities is Guadalajara, the capital city, which has a metropolitan area--composed of San Pedro Tlaquepaque, Tonalá, Zapopan, Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, El Salto, Juanacatlán, Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos and Guadalajara--that is home to about 5 million.

Disapperances in Jalisco

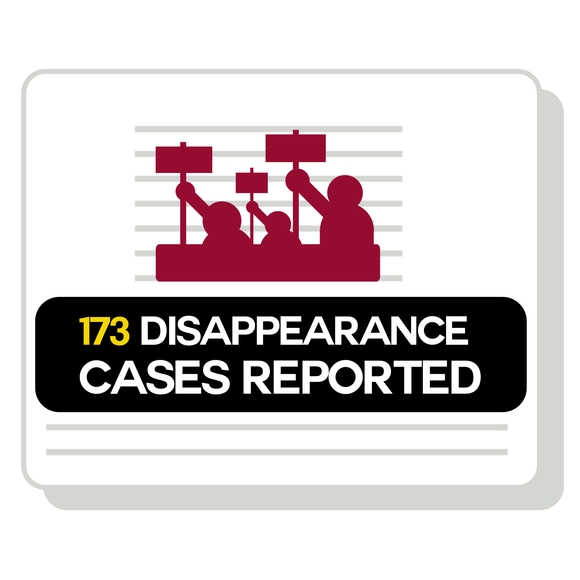

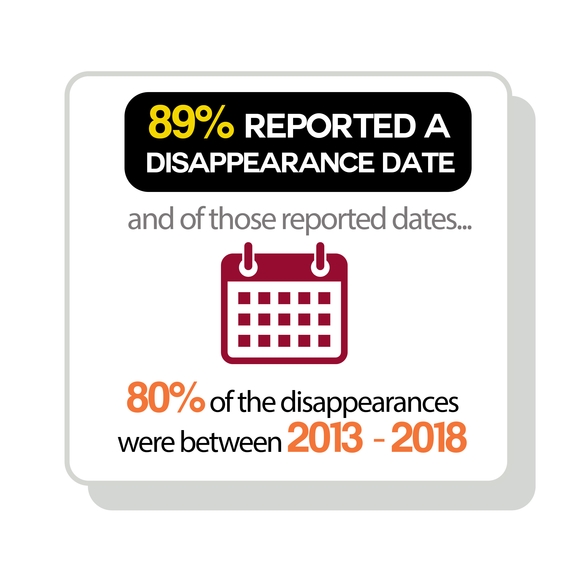

Systematic disappearances in Jalisco skyrocketed after 2013 and press reports rose accordingly. According to the National Search Commission in Mexico, the state of Jalisco had a total of 7,376 disappeared or missing persons between 2009 and 2018. The Observatory’s press database includes 173 cases of disappeared victims in Jalisco during this time period. This five-year time period accounts for 8 out of 10 (80%) of all disappearances reported in Jalisco during the decade, with a total of 138 victims. During these five years, disappearances were reported at a fairly consistent rate, with an average of 23 victims reported per year.

|

|

Circumstances have only worsened since 2018. The rate of disappearance accelerated, with an additional 9,593 reported disappearances between 2018 and 2021, making Jalisco one of the most serious sites of enforced disappearances in the entire country.

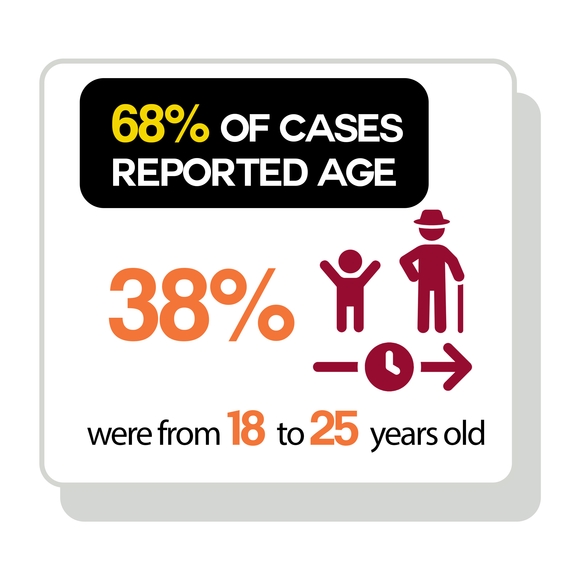

According to the press reports from 2009 to 2018, 7 of 10 (70%) victims were disappeared in Jalisco alone, while 3 of 10 (30%) were reported to have been disappeared in a group. This is a markedly different pattern than in other states where the tendency was for the press to report an even number of group and individual victims. Similar to our findings in other states, the vast majority of reported victims of disappearances were male; 80% victims were identified as males and 20% of disappearance victims were female. The youth of the disappearance victims is consistent with trends observed in other states: 38% of victims were reported as being between the ages of 18 and 25 years old.

|

|

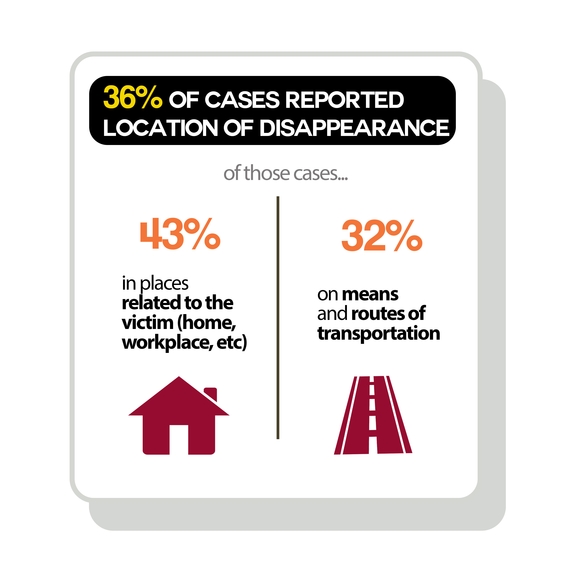

When reported, three-quarters of disappearances took place in locations related to the victim - house, workplace, private property - (43%) or on means and routes of transportation (32%).

|

|

Disappearances were reported in 23 of the 125 municipalities in Jalisco. Out of cases where municipality was reported, the three municipalities with the highest reported disappearances were Lagos de Moreno, Zapopan, and Guadalajara. Compared to other states, the press reported disappearances in more municipalities, exhibiting a more dispersed pattern of disappearances. The press did not report the municipality of disappearance in 40% of cases.

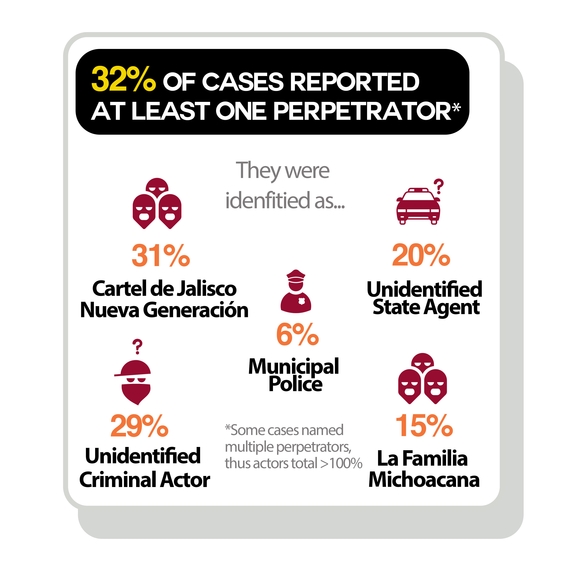

In Jalisco, the press did not report a suspected perpetrator in more than two-thirds (68%) of cases. When a perpetrator was reported, in over half (55%) of the cases, the victim was disappeared by a private actor (including criminal organizations), in 29% of cases, the press held a state actor responsible, and in 16% they acted together. The group reported as responsible for the highest number of disappearances was the Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generacion, who was involved in 31% (17 cases) of reported disappearances.

|

|

Criminalizing the Victim: an excuse for impunity

Press stories about disappearances in Jalisco rarely reported on the state’s efforts to establish accountability for the crimes. In 89% of reported cases in Jalisco, the coverage did not include information about an investigation or charges in the crime. Only 13 reported cases (11%) suggested the initiation of a court case and, of those, only five cases reported a conviction or a sentence; however, no cases specified the type of sentence.

Even when criminal responsibility for disappearances was discussed in these cases, those facing jail time were not the only ones under scrutiny. The victims frequently stand accused, without indications of proof, of involvement in drug cartels and other unscrupulous acts. This phenomenon is illustrated in the reporting about the disappearance and murder of Andres B (age 15) and Luis Antonio O (age 14). Both boys were kidnapped and killed because they bullied the son of a drug lord, as reported. Press coverage included assertions by the attorney general in a press conference concerning the boys’ supposed interest and potential involvement in narcotrafficking. Instead of treating these victims as such, prosecutors and investigators alike publicly speculated about Andres B’s and Luis Antonio O’s involvement in criminal activity and implied that they were at least partially responsible for their own deaths.

|

|

A downloadable PDF of these infographics is available here.

Case of the Three Film Students

In the middle of a project for the University of Audiovisual Media in Guadalajara, three film students were disappeared, never to be seen or heard from again. The students' names were Javier Salomon Aceves Gastélum, Marco Garcia Francisco Ávalos, and Jesus Daniel Díaz. On March 19th, 2018, during their spring break, the students decided to shoot their film project at Javier’s aunt’s house in Tonala, Jalisco. The filming location can be described as a country house, outside the city of Guadalajara, and in more of a rural area. Unknown to them, the house was also frequented by the Nueva Plaza gang.

Nueva Plaza is a gang that rivals one of Mexico's most powerful cartels, the Cartel Jalisco New Generation. During the spring of 2018, both of the cartels were preparing for the release of Diego Gabriel Mejía, a member of the Nueva Plaza cartel who had previously been detained in the same house where the students filmed their project. In anticipation of Mejías release, the Cartel Jalisco New Generation paid close attention to the house, keeping it under surveillance. It was also presumed that El Cholo, Nueva Plaza’s leader, might turn up there. Jalisco’s attorney general’s office believes that the students' presence on the property created suspicion causing the Cartel Jalisco New Generation to react.

Leaving the house after filming one day, the students experienced car trouble. The mechanical problems forced them, along with four of their peers, to pull over. They were then approached by two vehicles. Out of the vehicles came armed men dressed as law enforcement. After ordering the students to get down on the ground, they forced Javier, Marco, and Jesus into one of their vehicles. Javier’s cousin, Alejandra, was one of the others with them during the confrontation. She recounts seeing men with guns telling them they were police and ordering them to duck down. When she lifted her head, the vehicles were gone. The three students were then driven to a house six kilometers away. Authorities would later find uniforms with the Attorney General's Office logo and army exclusive weapons at the safe house.

Once the students were secured in the new location, members of the Cartel Jalisco New Generation began beating and torturing them to gain information on the Nueva Plaza cartel. Javier unfortunately succumbed to his wounds during the brutal interrogation. According to the chief investigator on the case, Lizette Torres, after Javier's death, the gang members decided they needed to execute Marco and Jesus. Once all three students were dead, it is presumed that their bodies were taken to another location, a nearby farm, to be dissolved in acid. When authorities investigated this location on April 18th, they discovered 46 cans of sulfuric acid and 18 different genetic profiles, leading them to believe that the house had previously been used to dispose of bodies. On April 23rd, Jesus and Marco’s genetic material was identified. Javier’s DNA was never confirmed.

On that same day, April 23rd, two men, Omar ‘N’ and Gerardo ‘N’ were arrested in association with the murders. Both of the men are assumed to be members of the Cartel Jalisco New Generation. Omar ‘N’ confessed that he, along Gerado ‘N’, were personally responsible for dissolving the bodies in acid on the farm. Omar ‘N’ also goes by the rapper name QBA and is well known in the region and on YouTube. On May 10th, a third person was arrested who is believed to be connected to the crimes. Johnathan ‘N’ was arrested in Mepotec after fleeing from police for months. It is reported that at least 8 people participated in the students disappearance and murder.

The family of one of the three students rejected the police’s narrative, fearing that the prosecutors were trying to close the case and move on too quickly. They believe that the evidence presented by the Attorney General's office lacked legal support. They also understood that the case framed the government in an unfavorable way very close to the July 1st general election. Criminal expert María Lina Guetierrez explained that there will never be certainty surrounding what happened to the students.

The case gained international attention, thanks in part to Oscar winning director Guillermo del Toro, who is a Guadalajara native. With the help of his 1.36 million twitter followers, he assisted in spreading the hashtags #NoSonTresSomosTodxs and #LosTresEstudiantesDeCine. Celebrities like del Toro not only drew attention to the case of the three cine students, but to disappearances in Jalisco and in Mexico in general. Thousands protested the students' disappearance in Guadalajara and in Mexico City, and continue to do so especially on March 19, the date of the students’ disappearance.

Unlike most disappearances in Mexico, the case of the three films students gathered a significant amount of press coverage. Google searching “three film students in Mexico” in Spanish or English will produce millions of results. This is what sets this case apart from others analysed in this database and why it was not included.

Javier, nicknamed Salo, was 25 years old. He is described as dedicated, with a bright future in cinematography. He also had a passion for playing the drums. Marco Avalo was 20 years old. He dreamed of being a director and was known for bringing fun to his friend group. Daniel Diaz was also 20 years old. He was a calm and joyful person who enjoyed playing soccer.

Students from the University of Audiovisual Media released a video titled LOS TRES ESTUDIANTES DE CINE. The video encompasses their fear, betrayal, and plea for help.

The economy of Jalisco, as in Nuevo León and Coahuila, is among the strongest in Mexico. Primarily reliant upon tourism, the service sector, and manufacturing, the GDP of this state in 2018 was 1,575,126 million pesos, or 69,683 million USD. Reflective of the economic strength of Jalisco is its low unemployment rate; until the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was 2.98%.

Jalisco, like Coahuila, has a Human Development Score and educational achievement statistics that would suggest the enjoyment of a high standard of living. While Jalisco residents receive an average of 9.2 years of formal education, resulting in a literacy rate of 88.3% and live in a state whose Human Development Index is among the highest in Mexico, the sense of insecurity in the state is contrary to those positive indicators. The more subjective reality of living in Jalisco is reflected in the fact that 79% of women and 72% of men report feeling unsafe in public, while 72% of women and 69.8% of men expect to be the eventual victim of crime in a state where official reports acknowledge the occurrence of almost 2.5 million crimes in 2017 alone. Feelings of insecurity are exacerbated by low trust in law enforcement (58% of state residents trust the police) and even lower trust (49.5%) in judges.

The state government of Jalisco, after years of being dominated by members of the more conservative party, Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), is now under the leadership of Enrique Alfaro Ramírez and the Partido Movimiento Ciudadano. The Partido Movimiento Ciudadano claims to have centrist ideologies, focused on the realization of human rights, the participation of citizens in government, gender equality, and a renewed commitment to social democracy. The economic stance of the governing party is one which looks to satisfy both those on the left and right of the political spectrum; the guiding ideology of this party asserts that the free market is the ideal system around which to produce and distribute goods and services. It does, however, recognize and advocate for the benefits of the implementation of state regulation in economic affairs.

While the political party which is currently dominant is more moderate, Jalisco is characterized by its deeply conservative and traditional society, in line with a large Catholic population. However, given the high concentration of universities in this state, liberal ideas are gaining ground among youth, ideas and convictions which have manifested in a wide array of protests related to -- among other things-- disappearances in Mexico, police corruption, LGBTQ+ rights, and feminism.

In 2019, given the dramatic numbers of disappearances in Jalisco, the state government announced a plan for preventing disappearances and finding disappeared individuals in (Ramirez, Enrique Alfaro). Among its main goals are the prioritization of the truth, the centralization of victims in investigations, and the assumption of official responsibility.

These goals are necessary for the confrontation of the phenomenon of enforced disappearances in Jalisco. According to the information gathered from the Observatory’s database, in only 29% of cases did the press report an official search for victims of enforced disappearances.

While, from 2018 to 2019, the Jalisco state government reports having located 1,920 living victims of disappearances, the state is still far behind in establishing an effective legal system capable of preventing disappearances and of locating victims during the critical window of time in which they can still be found alive. Governor Enrique Alfaro Ramírez himself acknowledges both a lack of coordination and communication among the four institutions designed to combat disappearances, as well as a general lack of qualified personnel.

The four institutions in place for the prevention and investigation of disappearances are the Fiscalía especializada en personas desaparecidas [specialized prosecutor for disappeared persons], el Instituto jalisciense de ciencias forenses [Jalisco Institute of forensic sciences], la Comisión ejecutiva estatal de atención a víctimas [State executive commission for attention to victims], and la Comisión de búsqueda de personas del estado de Jalisco [State search commission for disappeared persons]. The government of Jalisco has secured additional funding for the support of these organizations. The state government reports that it is in the process of training personnel, of building relationships with expert organizations such as the Red Cross, and of establishing a system of communication among all four entities. The state government has stated that its main goal is to assist families- both psychologically and legally- in the navigation of the difficulties of life after the disappearance of a loved one.

The government of Jalisco has developed three new pieces of legislation aimed to combat disappearances in the state. The three laws- la Ley de Personas Desaparecidas en Jalisco [Law of Disappeared Persons in Jalisco], la Ley Estatal de Atención a las Víctimas [State Law for Attention to Victims], and la Ley de Declaración especial de ausencia [Law on special declarations of absence] are all in different stages of development and are intended to create an infrastructure better attuned to the demands of disappearance cases, the needs of the victims of these crimes, the reporting of disappearances, and the localization of victims.

In late February 2021, the state of Jalisco approved the Ley de Personas Desaparecidas which seeks to speed up the search for the victims of disappearances through better coordination between agencies. Jalisco has now three months since the approval to harmonize the new law with the current reglamentation. The Coordinating Committee for the new State Search System must be set within a maximum of 30 days after the entry into force of the law. In its first session it will have to issue the criteria for personnel training and in the second meeting it will approve the state search program to be proposed by the State Search Commission. As disappearances rise in this state, the government is responding to public pressure by designing a system that is attuned to and effective in dealing with such serious crimes.

Organized crime in Jalisco is dominated, in large part, by the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cartel (CJNG). With its influence evident in many legal and illicit sectors, the CJNG is involved deeply in the trafficking of drugs and arms and, behind Los Zetas, is considered to be the second most violent cartel in the country. The reach of CJNG has grown and extends beyond the state boundaries of Jalisco; it is estimated that this cartel operates in 22 of Mexico’s 32 states. Such growth has increased the power of the cartel and driven a huge spike in violent crime and conflict to the state.

Violence from intra-cartel conflicts is concentrated both in the metropolitan district centered around Guadalajara and along the borders that this state shares with other states. Along Jalisco’s border with Colima to the south, for example, CJNG is in conflict with La Nueva Familia Michoacana, the Cártel de Sinaloa, and Los Caballeros Templarios. On the border separating Jalisco and Nayarit, CJNG is engaged in conflict with Los Beltran, and on the border between Jalisco and Zacatecas, CJNG is in conflict with Los Zetas.

The recent growth of CJNG and its engagement with other cartels has reportedly resulted in an internal rupture; one of the most prominent rivals of this cartel in Jalisco is the Cartel Nueva Plaza- one which was created by former members of CJNG. Both cartels use social media platforms and videos for recruitment and the defamation of the other.

Proyecto Diez

Formed in 1981, this organization was created after the firing of Felipe Cobian Rosales from his previous position as a reporter with a now reinvented radio broadcasting company, previously known as Notisistema. In solidarity with Rosales and in support of his mission to expose injustice and corruption in Jalisco, nine other employees of Notisistema resigned from their positions and joined Rosales in the establishment of Proyecto Diez.

The mission of Proyecto Diez continues to be the diffusion of information intended to uncover the reality of life in Jalisco from a critical perspective; its fundamental principles are based in the maintenance of independent, unbiased press outlets. In alignment with its promise to provide readers with unbiased reports, both online and in print, Proyecto Diez claims to not be supported by nor to promote any political party; it claims that its mission and actions goes beyond politics.

Proyecto Diez reports that its mission is motivated by the desire to create a well-informed society; a society that is aware of events that may be left out of political conferences or mainstream news reports.

El Informador

El Informador, like Proyecto Diez, is an independent news outlet based in Guadalajara, Jalisco. Unlike Proyecto Diez, El Informador has a long history in this state. Formed in 1917 by Jesus Alvarez de Castillo, this news outlet is the largest in Jalisco and the sixth largest in all of Mexico.

El Informador publishes international, economic, regional, and sports news in addition to providing consumers with lighter content related to pop culture.

This newspaper, like many others, publishes articles both online and in print form. Additionally, it allows online users access to its digital archives of material published since its founding.

Unlike Proyecto Diez, El Informador aims to be a politically neutral publication and does not have any information on its website detailing its political stance; it does not negate having ties to any political party. El Informador, while an independent news source, does not operate with the explicit political intent to realize social justice through the circulation of critical information.