Enforced Disappearance under International Law

Enforced disappearance is universally and unconditionally prohibited as a human rights violation. It is prohibited under international law in peacetime or armed conflict, and is a crime in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. The 2006 International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance defines an enforced disappearance as:

the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law. (Article 2)

Disappearance is a violation regardless whether it is for a short term or long term. It is also a continuous crime, so that the government is responsible for the violation until the whereabouts of the missing person are determined. Relatives of persons who have disappeared have the right to know the truth regarding the fate and whereabouts of their loved ones.

An enforced disappearance consists of multiple violations of human rights -- the right to life, the right to be free from torture, the right to be free from arbitrary detention, the right to recognition before the law, and the right to a fair trial. Disappearances also result in severe economic and social rights violations for direct and indirect victims. These crimes completely undermine the victims’ rights to work, to care for their families and to live healthy, sustainable lives. (UN Factsheet No. 6, Rev. 3).

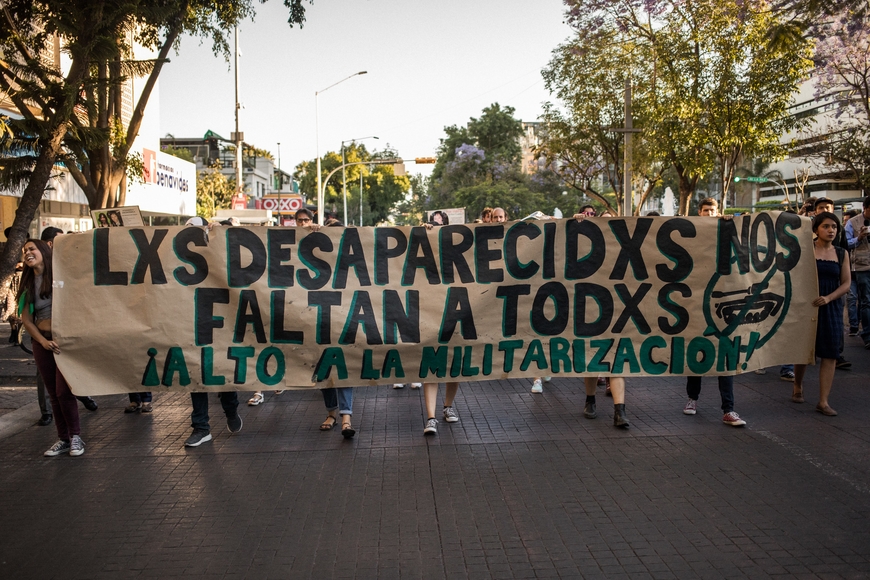

The international human rights community has spoken out consistently and assertively about the problem of disappearances in Mexico. The Inter-American system has found the Mexican government responsible for disappearances in its case law on México (Radilla, Campo de Algodon) and put in place precautionary measures and an unprecedented international investigative group and a special follow-up mechanism of the country’s most notorious mass disappearance of the 43 normal school students in Ayotzinapa.

Similarly, the United Nations has condemned the pattern of disappearances in México, through reports of the Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances, the Committee on Enforced Disappearances and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

For purposes of this study, we include all disappearance cases in our analysis, recognizing that the line between a crime by private actors and a human rights violation by state actors is very thin indeed. Because many, if not most disappearances are carried out by organised crime or other private actors without a verifiable connection to the state, Mexico’s response to these international concerns had been to differentiate disappearances from various crimes that are “in the nature of enforced disappearance” but take place without the authorisation, support or acquiescence of the State (Report of Mexico to CED, 2014: paras. 94, et seq.)

While many disappearances in México are committed by, or with the ‘authorization, support or acquiescence’ of State authorities, there are many cases where state involvement in the disappearance cannot be proven or where the crime is carried out by non-state criminal actors. States, however, are responsible not only for direct involvement but also for their omissions in disappearance cases -- failure to search, failing to investigate, or delay that results in further endangerment of the disappeared person. A failure to respect the duty to investigate is a breach of the right to life. (Minnesota Protocol 2017, para. 8(c)); UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, UN doc. A/70/304)

In 2017, México adopted the General Law on the Forced Disappearance of Persons, Disappearances Committed by Individuals, which categorized two types of disappearances as crimes. The first is the crime of enforced disappearance, which, in line with the international definition, is one committed by an authority or a non-state actor with the acquiescence of a public official. The second crime defined by the General Law concerns disappearances committed by private actors who deprive a person of liberty for the purpose of concealing the victim or his/her fate or whereabouts. The General Law has established search mechanisms and registries of disappearances that embrace the victims of both of these categories, recognizing the state’s legal responsibilities for preventing disappearances and for publishing perpetrators -- whether state or private actors.